Covid Spurs Diversity

Bayoumi, NLM Promote Graphic Medicine

When you think of comics, you may picture something like Peanuts or the Marvel series. But the field encompasses topics far beyond the Sunday funnies page.

Dr. Soha Bayoumi of Johns Hopkins University recently gave an NLM History Talk on graphic medicine, a freshly minted term that describes “the intersection of the medium of comics and discourse of health care.” NLM is growing its graphic medicine collection and has created a traveling exhibition, “Graphic Medicine: Ill-Conceived & Well-Drawn!”

Graphic medicine represents a collision of interests for Bayoumi, who uses she/they pronouns, as it combines her love for comics, medical humanities and the history of medicine.

Although graphic medicine has existed in various forms since approximately the 1950s, the genre as Bayoumi defines it began to emerge in the mid-2000s and the term itself was defined in The Graphic Medicine Manifesto in 2015.

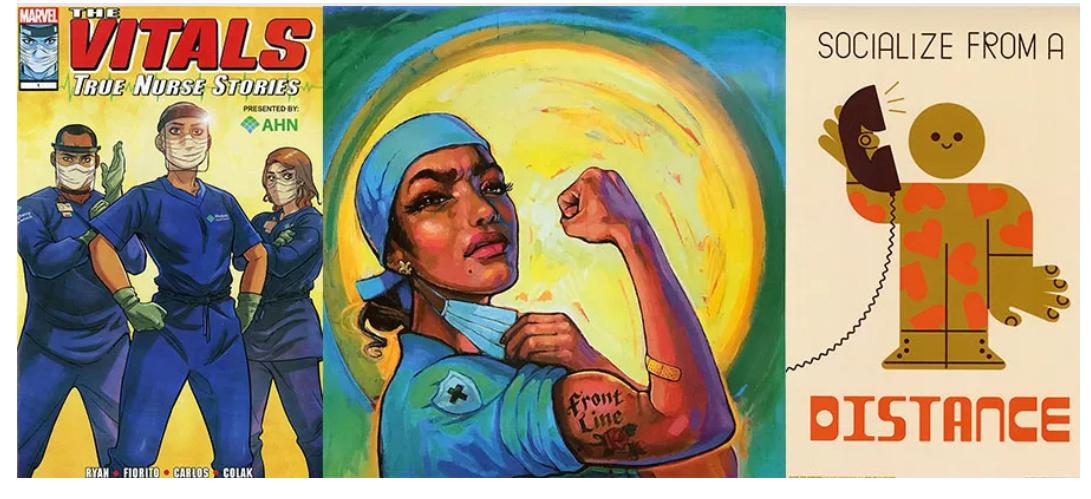

Many pre-pandemic comics were written by or featured White patients or providers. Comics produced during the Covid-19 outbreak, Bayoumi argued, present “a much more significant diversity of creators and narratives that touch upon the lives and experiences of Black and indigenous people of color [BIPOC]...and communities and other marginalized identities.”

Comic Qualities

What makes comics interesting—not just for general consumers, but also for health care professionals, scholars and patients? Bayoumi, a lifelong fan of comics, said the often-abstract art used by comic artists can be appealing to readers.

“Think of Charlie Brown,” they said. “Simplistic drawings can still move readers and are very identifiable.”

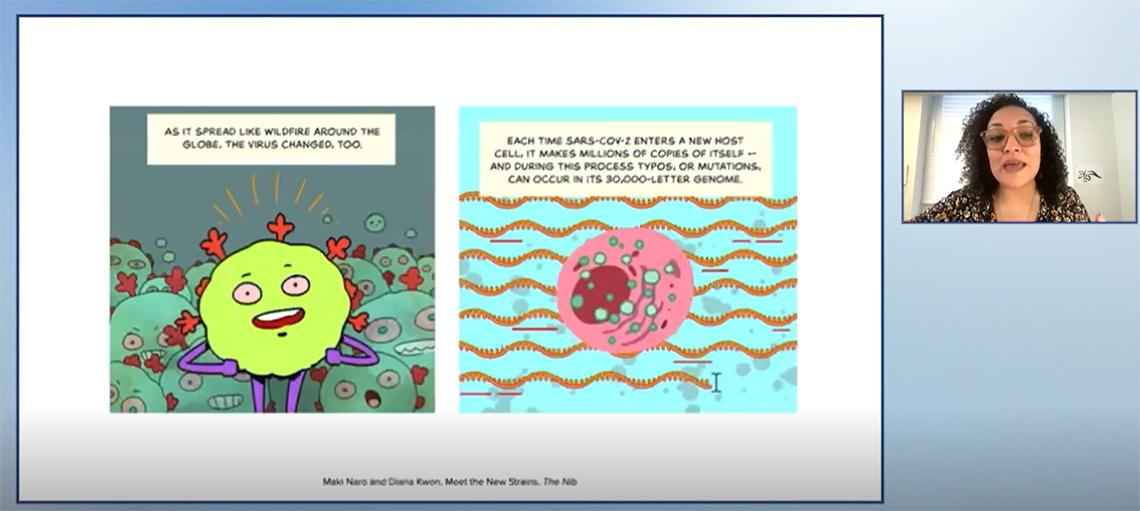

The combination of text and images in comics can also allow the author to convey points in a concise and effective manner. And the images can be emotionally evocative in ways that are difficult for words to accomplish. Graphic medicine allows the author to “depict the ‘objective’ world while [simultaneously] depicting the patient’s inner perception,” Bayoumi explained.

For patients, graphic medicine can represent a way to exert control over their own narrative, Bayoumi said. Patients may feel as though they have lost control over what is happening within their own bodies, but telling their story in their own words can be empowering and even “cathartic,” according to Bayoumi.

Scholars have even coined a term for the subgenre of biographies (in comic form) that focus on a person’s illness: graphic pathography. These works help diversify the depiction of diseases. Formerly the domain of doctors and medical illustrators who standardized the way diseases were visualized, graphic medicine gives patients and caregivers the power to share how they are individually affected.

Medical comics also can serve an instructional purpose—consider, for instance, the informational posters in your doctor’s office. Providers have also begun writing their own graphic narratives. Annals of Internal Medicine began publishing comics written by health care workers in 2013, for example. Provider narratives touch on a wide range of topics, from the struggles of being a working parent to the lingering guilt of losing a patient.

‘Why So White?’

Bayoumi and other scholars of graphic medicine observed a trend in the pre-pandemic makeup of authors: they were overwhelmingly White and middle class. But, why?

The majority of editors and publishers in the U.S. are White—about 76 percent, which may lead to an unconscious preference for White stories.

Graphic narratives are incredibly time-consuming to produce—time and effort that ill writers may not be able to commit to easily. Additionally, Bayoumi hypothesized, BIPOC individuals may be more likely to have multiple jobs and lower socioeconomic status, with less free time to devote to intensive topics on top of having a serious illness.

The weight of stigma might also be a roadblock; the stigma of illness combined with the stigma of racism often “compels [BIPOC] to keep their woes quiet.”

Common ailments for BIPOC (such as heart disease) are often disparaged as lifestyle diseases caused by poor choices alone, Bayoumi said, “so few people of color are likely to find a space that would allow them to share their experiences of illness without fear of judgment.”

Graphic narratives written by White authors are often what scholars deem “confessional narratives.” How might works such as Rachel Lindsay’s Rx, which feature a White author’s struggle with bipolar disorder, be viewed differently if the author was of a different race?

Bayoumi quoted Christopher Grobe’s The Art of Confession: “Who will be celebrated for confessing?”

‘Covidity’

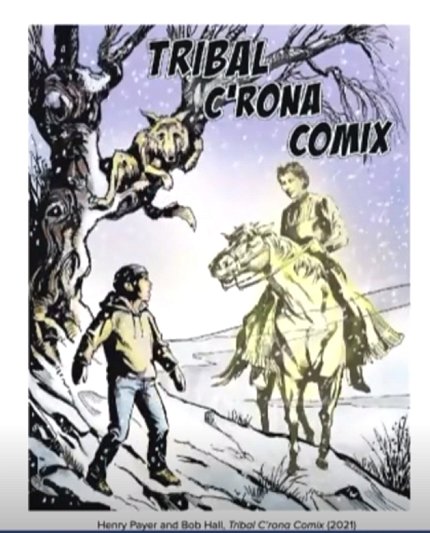

A term denoting the individual and collective philosophical, material and wide-ranging emotional responses to the pandemic, “covidity” has become a major feature in graphic medicine since the beginning of the health crisis. This trend has been accompanied by a significant increase in the diversity of graphic medicine creators.

Bayoumi posited that the “twindemic” of Covid and systemic racism contributed to this rise in diversity. Covid was “almost an invitation to write about how it was affecting communities of color disproportionately,” they said. “Racial inequalities [were] exacerbated.”

Authors wrote about the effects of the pandemic on indigenous communities, the rise of anti-Asian hate, how hospitals in underserved communities often had poorer outcomes—to name just a few topics.

Photo: NLM

Bayoumi referenced The Graphic Medicine Manifesto throughout her talk. The book is a significant development in graphic medicine because it established the principles of graphic medicine and began to map the field.

The graphic medicine ethos defined by the book aligned particularly well with Bayoumi’s talk: “‘Graphic medicine is also a movement for change that challenges the dominant methods of scholarship in health care, offering a more inclusive perspective of medicine, illness, disability, caregiving and being cared for.’”

As Bayoumi observed, the field’s inclusivity has grown substantially since the start of the pandemic. “I hope these changes induced by Covid will be lasting,” they concluded.

To view the archived lecture, visit https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=48675