Global Medicine in History

Soon Explores How the Chinese Diaspora Shaped Medicine in the Region

A group of overseas Chinese doctors brought Western medicine to China and Taiwan over the last century. They promoted transformative medical practices—blood banking, mass medical training and mobile medical units—and their efforts left a lasting impact in the region.

At a recent National Library of Medicine history talk, Dr. Wayne Soon, associate professor in the history of medicine program at the University of Minnesota, discussed two case studies to illustrate how the Chinese diaspora was integral in shaping biomedicine in China and Taiwan from 1937 to 1970.

“To make biomedicine work, I argue the members of the Chinese diaspora drew resources, ideas and support from the carefully cultivated contexts in international organizations and universities,” said Soon during the virtual lecture. “They tap into diasporic organizations in Southeast Asia, North America and Western Europe. These connections help them to deal with myriad local actors in China.”

Drawing from government documents, scientific and military reports, medical texts and other NLM sources and various archives and libraries across the world, he makes the case for a new definition of global medicine that highlights the multidirectional flow of medical practices and ideas.

This redefined concept of global medicine, Soon argues, “was made possible by the Overseas Chinese leveraging the multicultural identities, Western expertise, desire for medical intervention and transnational connections to make biomedicine visible and possible to a local and global audience.”

The First Chinese Blood Bank

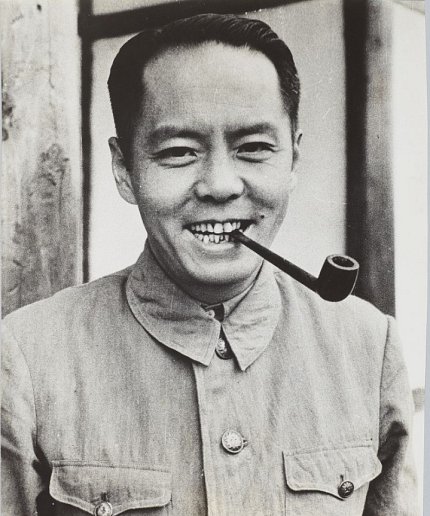

Photo: Columbia University rare book and manuscript library

Establishing the first Chinese blood bank is a story of cross-cultural outreach.

During World War II, Singapore-born and Edinburgh-educated Dr. Robert Kho-seng Lim—who headed the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps—solicited funding from the American Bureau for Medical Aid to China (ABMAC) to train Chinese American Dr. Helena Wong and Chinese Canadian Dr. Yi Chien-lung at Columbia in the latest blood banking technologies. Together with Chinese American Adet Lin, they then set up a trial blood bank in New York City, appealing to Americans of all races to donate blood.

One group that eagerly heeded the call was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

“African American activities in the NAACP were determined to challenge the existing segregation of blood donation by the American Red Cross by donating to the first desegregated blood bank in the United States,” said Soon.

Japanese and Chinese Americans also eagerly donated blood, wanting to support the war effort.

Photo: Columbia University rare book and manuscript library

Lim, Lin and Wong sought to replicate their success in China. They set up a blood bank in Kunming, a city in Yunnan province, but faced major challenges. Without reliable electricity, they could not employ the imported blood banking equipment needed to run the centrifuge, dehydrator and autoclave, used to sterilize medical equipment. As a result, contamination of blood remained a significant problem.

To improve conditions, a Chinese American engineer added a hand crank to many of the machines.

And despite outreach efforts, there was a shortage of donors. Few Chinese civilians or American soldiers donated blood in Kunming, noted Soon.

Furthermore, “Wong and Lin unnecessarily disqualified many soldiers from donating blood,” Soon said. “And they did not explain to the soldiers the philosophy and processes of blood banking and transfusion.” Unaware that their donated blood would help others in need, he said, “many soldiers complained their blood was taken away rather than put in their backpacks for later use.”

Photo: Columbia University rare book and manuscript library

The blood bank did succeed later by partnering with local universities and companies, drawing much-needed blood from students and workers.

“This donated blood helped to save many American and Chinese lives on the warfront,” Soon said.

The Chinese diaspora had established a military medical complex during World War II—the Chinese Red Cross, the Emergency Medical Service Training School and the first Chinese blood bank—that together trained more than 15,000 medical personnel and saved more than four million lives.

Moving a Medical Institution to Taiwan

After World War II, Lim sought to reconstruct the mighty military medical complex into a comprehensive postwar medical center. But for political and other reasons, funding from the Chinese diaspora and American aid organizations had greatly declined.

Photo: Columbia University rare book and manuscript library

Lim established the National Defense Medical Center (NDMC)—a military medical school—in 1946 and overcame funding woes by taking over abandoned Japanese medical buildings and supplies left over in Shanghai, Soon explained. But in 1948, as China’s ongoing civil war flared, the NDMC was instructed to relocate to Taiwan.

Many doctors were reluctant to move but a third of instructors and half of the students transferred to Taipei. The NDMC in Taiwan initially was encumbered by a lack of proper infrastructure, space and resources. But Lim and his Chinese American colleague, Allan Lau, secured millions of pounds of provisions, including more than 14,000 cases of medical supplies.

Still, problems persisted on the ground. “Personnel did not have enough food to eat, cadavers for research, physical classrooms to learn in and dorms to live in,” said Soon.

“To redress the NDMC’s long-term viability, the NDMC leaders developed the discourse of the center as an essential anti-communist medical institution for vulnerable overseas Chinese,” he said.

NDMC then enlisted U.S. President Eisenhower’s Foreign Operations Administration to secure funding and increase student enrollment. The center trained thousands of medical personnel in Taiwan. Funding from other U.S. agencies led to construction of NDMC’s teaching hospital—the Taipei Veteran Hospital—which remains a top hospital in the country today.

Generations of NDMC graduates have become prominent doctors and nurses who played a critical role in health care, including fighting the SARS and Covid-19 epidemics.

Another legacy of these efforts is the active participation of diasporic women medical personnel who provided care and promoted research in wartime China and postwar Taiwan and paved the way for many other women to take on increasingly prominent roles in health care today.

“The global history of medicine in China and Taiwan was predicated on the efforts of the Chinese diaspora, who leveraged international connections, medical expertise and linguistic talents to build medical institutions in 20th century China and Taiwan,” Soon said. Their efforts helped to save many lives during World War II and beyond.

For more on this topic, see the NLM's blog, "Global Medicine in China and Taiwan: A Diasporic History."