‘Zoom Fatigue’

Psychologist Discusses Ways to Recover from Virtual Exhaustion

“Can you see me?” “You’re muted.” “My internet cut out. Would you repeat that?”

The annoyances and flubs that commonly occur during virtual meetings seemed less frustrating during the pandemic when virtual platforms such as Zoom were a lifeline to the outside world. Now, in this hybrid world, our tolerance appears to be waning. Why are virtual meetings so exhausting? A psychologist recently offered some reasons for the fatigue and tips for recovery.

“It’s not lost on me that I’m talking about Zoom fatigue on a Zoom meeting; I apologize if I’m feeding into the fatigue,” said Dr. Allison Gabriel, an organizational psychologist and the Thomas J. Howatt chair in management at Purdue University’s Mitchell E. Daniels Jr. School of Business. She spoke at a recent NIH Deputy Director for Management (DDM) seminar.

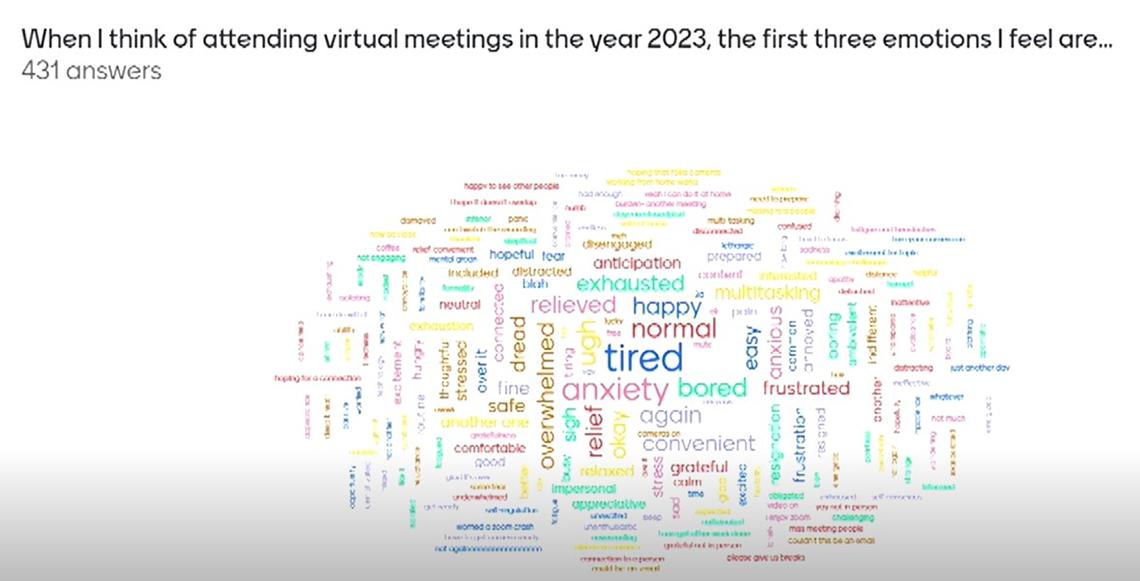

Gabriel asked attendees to name their first three emotions when thinking of attending virtual meetings now. Seconds later, hundreds of NIH’ers submitted their responses. The most common included tired, overwhelmed, anxious, dread, frustrated, annoyed, bored and disengaged. Another frequent response: “ugh.”

But many replies were positive: normal, relief, happy, safe, appreciative. This dichotomy is seen across the board when Gabriel speaks to different groups. Yes, there’s frustration, but many also express gratitude for the convenience of virtual meetings.

Whether people view online meetings favorably or with dread, Zoom fatigue is real. Interestingly, according to Gabriel’s research, it has little to do with the number of virtual meetings or the amount of time spent in them on a daily basis. Instead, one of the biggest culprits is being on camera.

Photo: Girts Ragelis/shutterstock

“We suspected that being on camera heightened the sense of being watched,” she said, and the need to make a good impression, which compels people to constantly check themselves—their hair, mannerisms, the lighting—on camera.

Could hiding self-view be a solution? Possibly. But another challenge is picking up nonverbal cues, such as nodding, that are easier to detect when in the same room. “Being on camera is also really distracting,” Gabriel said, making it harder to process those cues online.

To investigate the phenomenon of Zoom fatigue, Gabriel and her colleagues conducted a study in 2020 with a remote organization called BroadPath. Working with 103 people over a four-week period, they manipulated and compared camera use and surveyed each person daily about their experience. The researchers considered gender, job tenure and duration and frequency of meetings among the variables.

“We found that being on camera was positively related to feeling fatigued,” Gabriel said. And the fatigue hindered participant engagement and the likelihood that they spoke up during meetings.

“That’s pretty shocking because that means the very thing that being on camera is supposed to promote—being engaged and being able to speak up more—is inadvertently getting hurt because people are exhausted from being on camera constantly,” she said.

Women reported more fatigue than men. And recently hired staff were also more fatigued, as they struggled to navigate the dynamics and the jargon.

“This suggests that constant virtual meetings can really upend experiences for certain groups of employees who may be more susceptible to interpersonal challenges,” Gabriel said.

Beyond being on camera, Gabriel described several other irritants unique to virtual meetings. One is interpersonal time theft—hogging attention or talking too long without seeking input. Another is disrespect for time—meetings starting late or running over. “This is easy to do with nobody standing to physically leave the room,” Gabriel said. Yet another: distracted or zoning-out participants.

Those who are actively participating often struggle with how to break into the conversation, short of interrupting. Of course, there are reaction buttons, such as raising a hand. Gabriel also suggested leaving the chat open and rolling live so participants can enter questions and feedback in real-time, allowing the speaker to integrate responses along the way.

“As leaders,” she said, “we underestimate our responsibility to cue people into the conversation versus just being the ones who drive the conversation.”

Offering more recovery tips, Gabriel reiterated the responsibility of leaders. “We have a huge impact on people’s well-being from the norms we set and encourage.”

In the first few minutes of a virtual meeting, she said, small talk can reduce anxiety, create a supportive environment, and help people connect, especially those newcomers. And in those first minutes, leaders should help set expectations for the meeting to reduce ambiguity and help people feel included and engaged.

Give employees their autonomy back, she advised. Limit forced camera use and consider whether a series of emails could replace a scheduled meeting.

On a broader level, she said, leaders should encourage staff to physically and mentally separate from work. “Recovery only works when supervisors support time away from work being truly away from work,” she said.

But while working, employees need breaks. When virtual meetings are stacked back-to-back, for example, people lose those micro breaks that they often got in person when walking between meetings or stopping to chat with a colleague. Help people reclaim time by staggering or shortening meetings and building breaks into them. “Let people stretch.”

Photo: Deborah Henken/NICHD

In spare time, people need to psychologically detach. Switch off work-related thoughts. Relax the mind. Exercise. Learn a new skill. Get out in nature.

“When [people] took time after working hours to enact their recovery in this way, they had increased sleep quality…lower emotional exhaustion the next morning and next workday,” she said. “They were more engaged, they helped people more and had greater personal initiative. They were really thriving when they came back to work.”

Norms keep changing, but virtual meetings are here to stay. That doesn’t mean it’s any less important to get to know and support colleagues.

“Emotions have a place at work,” said Gabriel. “They are cues into how people are feeling about productivity and well-being.” If colleagues say they are fatigued or anxious, leaders should ask how to better support them.

“There can be real value in creating cultures of authenticity, allowing employees to bring more of their full selves into the workplace, to talk about how they’re thinking and feeling, to understand who people are inside and outside of work,” Gabriel said. “I think that’s really powerful when it comes to recovery.”

Celebrate everything. Whether in-person or virtual, “Take nothing for granted,” she said. “Being at work should bring joy, not stress. Remember this when we gather.”