When Dead Cells Talk

NCI Investigator Discovers Signals that Spur Metastatic Cancer

One of the toughest challenges in cancer therapy is treating a relapse, when cancer cells become more stubborn and resistant, and the prognosis more precarious.

Earlier this year, Dr. Li Yang and her lab colleagues at the National Cancer Institute discovered a mechanism that may underlie cancer relapse. They found that dying cancer cells emit signals that can trigger the growth of nearby cancer cells.

The implications are vast, and she urges the cancer research community to follow up.

“We need an effort to investigate how dying cancer cells can also be a problem for the patient,” said Yang, senior investigator in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics. “Our studies show there’s an unexpected side to the story of killing tumor cells, and we need to be aware.”

The Bursting Balloon

It was somewhat of an accidental discovery, Yang recalled. “It was in the back of our minds that dying cancer cells are interesting by themselves,” she said. Many tumor cells die naturally in the body—during circulation or in a hostile immune microenvironment—and many more die during cancer treatment. But treatment rarely kills all malignant cells. Some survive, hide and stay dormant, then evolve and resurface, tougher than before, and often resistant to therapy.

“My lab became interested in the epigenetic [how the environment influences genes and cells] component of cancer cells because we believe that understanding these epigenetic changes may provide the answer for how cancer cells change when challenged with treatment and how they create diversity between each other.”

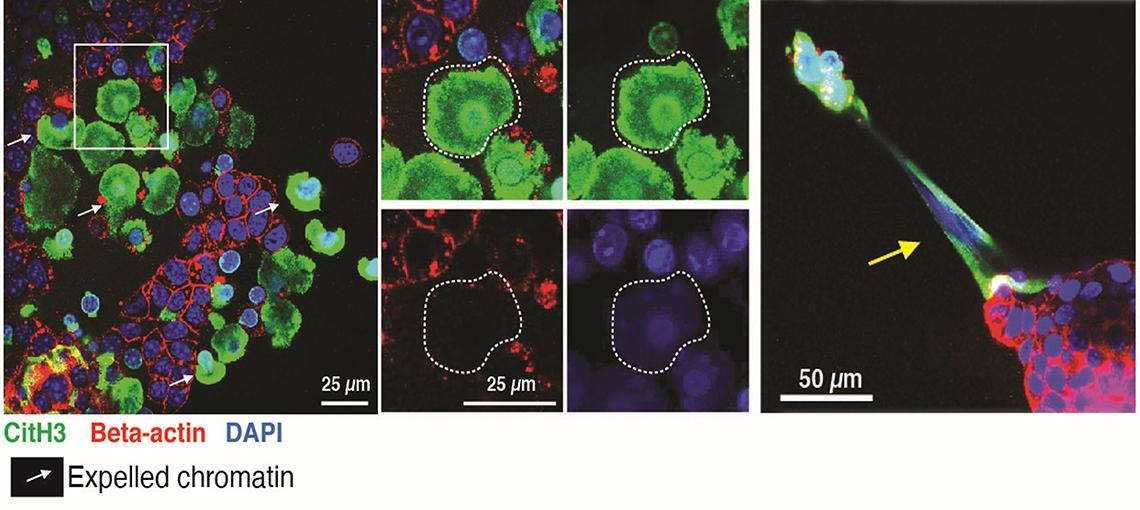

In the lab, her team discovered an epigenetic modifier called PAD4, which they found modifies chromatin—protein-encased strands of DNA.

“We found that dying cancer cells modify their chromatin,” Yang said. “The chromatin becomes expanded and then bursts. When they burst, they’re expunging out their contents.”

Photo: Yang lab

She further explained, “Imagine the cell as a balloon filled with things. When it expands beyond its limits, it bursts. Then all of the stuff inside—the nuclei, chromatin, DNA, proteins—gets spread out, far away.”

This was the start of a groundbreaking discovery. What they found surprised them.

Cancer’s Last Words

Photo: Yang lab

Upon further study, “We found out that the dying tumor cells have a way to support their community,” Yang said. “Perhaps they’re not dying in vain. In their death, they communicate to the surviving cancerous cells, ensuring the community’s survival.”

That was an unexpected revelation. They observed dying cancer cells sending signals to surviving cells, making them more resistant and enabling them to spread. “Cancer cells don’t act alone. Rather, they have quite a sophisticated network of communication,” she said.

Yang’s lab then traced these effects to a molecule, chromatin-bound S100a4, a factor that can stimulate the outgrowth of the living cancer cells. Is this mechanism of last words, of chromatin releasing from dying tumor cells, responsible for cancer relapse? This opens up an untapped avenue for exploration, toward reducing the chances of cancer recurring after treatment.

“Our investigations have found a molecular pathway containing key components that can be targeted therapeutically so that the cancer cells will not leave out the traces of chromatin that promote metastatic outgrowth,” she said. Building on this research, it might be possible to interrupt the conversation, to prevent dying cancer cells from sending the signals that provoke the spread of remaining cancer cells.

Yang recommends further study toward potential clinical trials. “The importance of our discovery goes beyond what we discovered. We hope that fellow cancer researchers, including principal investigators and young researchers, will join this effort and look into this uncovered area” that could identify new opportunities for cancer treatment and ultimately save lives.