Lard of the Flies

Rajan Studies How Fat Cells Communicate with the Brain

Photo: Robert Hood/Fred Hutch Cancer Center

Fruit flies have fat—but not too much, said Dr. Akhila Rajan during a recent Judith H. Greenberg Early Career Investigator Lecture.

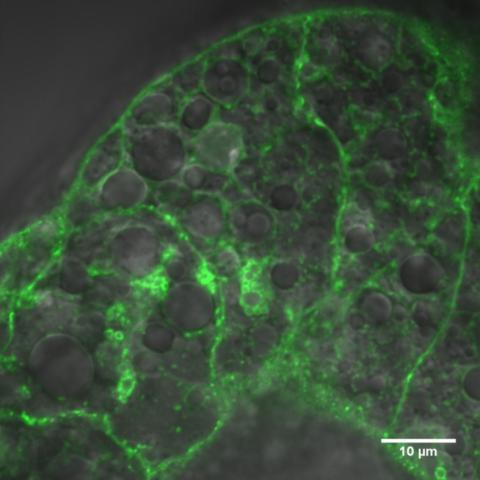

What little fat there is has helped scientists make unexpected findings about how fat cells communicate with the brain, said Rajan, associate professor in the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center’s basic sciences division. Fat cells, also referred to as adipocytes, are an organism’s primary energy storage organs.

All organisms are in a constant state of nutritional flux. Their brains communicate with fat cells to constantly balance food intake and nutrient storage with energy requirements. Rajan’s lab studies how the nutrient status—whether an organism is sated or starved—affects “our most primal functions like hunger, movement, sleep and immunity.”

A decade ago, she discovered fruit fly fat cells produce and secrete a protein called Upd2. The protein is a nutrient sensor. Upd2 communicates with a fly’s brain to control feeding behavior, growth and nutrient status. It affects the areas in the fly brain that are equivalent to the hypothalamus in flies, a region in the brain that regulates energy balance.

Photo: Rajan Lab

Upd2 is similar to leptin, another nutrient sensor that controls appetite in humans and other vertebrates. Signaling satiety is a primary function of these hormones, also known as adipokines. At the time, it was thought that humans and other mammals were the only organisms that produced a leptin-like protein. This proved fruit flies could be a model organism for the study of nutrient sensing.

In one experiment, Rajan fed flies a diet with 30% more sugar. When a fly’s sugar intake increased, so did Upd2. Conversely, Upd2 levels decreased when a fly wasn’t fed. The researchers also observed that flies cannot accurately sense their nutrient state when Upd2 production is altered.

“Our motivation in this particular work is to leverage this unexpected conservation between humans and flies to uncover biological principles that govern how organisms adapt to nutrient flux,” she said.

Photo: DALL.E

Most people think of leptin as an obesity signal. However, Rajan believes “we should be thinking about leptin during starvation.”

Studies in flies and mice have shown that adipokine levels drop when an animal doesn’t eat. In this starvation state, organisms begin conserving energy. A fly, for instance, won’t perform energy-consuming activities, such as laying eggs. This process must happen. Experiments have shown that flies that overproduce Upd2 have a shorter lifespan compared to control flies.

“We don’t fully understand how starvation status controls the release of adipokines,” she noted.

When a cell is starving, it begins a nutrient-scavenging process called autophagy. A protein called Atg8-LC3 plays an important part in the process. Right now, Rajan and her colleagues are trying to identify what happens when this process begins. She hopes to publish more on Atg8-LC3’s role in managing nutrient flux soon.

Photo: Christopher Wanjek

After her talk, Rajan participated in a brief question and answer session with Dr. Jon Lorsch, director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

In 2021, NIGMS renamed its Director’s Early Career Investigator Lecture Series to honor former deputy director Greenberg. The series was established in 2016 to encourage undergraduate students to pursue careers in biomedical research. The scope has since broadened to include graduate through postdoctoral students and other early-career scientists.

To watch the lecture, visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhzTApI-0BI.