New Links Discovered Between Brain, Surrounding Environment

Photo: NINDS

In a recent study of the brain’s waste drainage system, researchers from Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL), collaborating with NINDS investigators, discovered a direct connection between the brain and its tough protective covering, the dura mater. The links may allow waste fluid to leave the brain while also exposing the brain to immune cells and other signals coming from the dura.

This challenges the conventional wisdom that suggests the brain is cut off from its surroundings by a series of protective barriers, keeping it safe from chemicals and toxins lurking in the environment.

“Waste fluid moves from the brain into the body much like how sewage leaves our homes,” said Dr. Daniel Reich of NINDS. “In this study, we asked what happens once the ‘drain pipes’ leave the ‘house’—in this case, the brain—and connect up with the city sewer system within the body.”

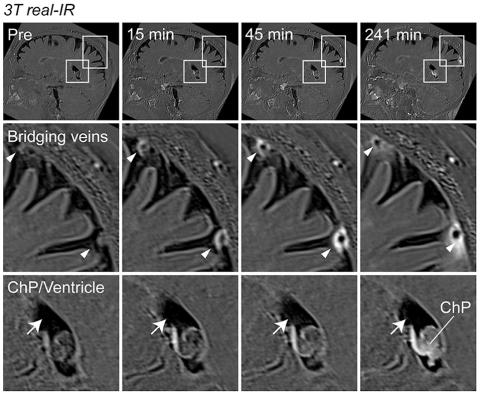

Reich’s lab used high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to observe the connection between the brain and body’s lymphatic systems in humans. Meanwhile, Dr. Jonathan Kipnis’s WUSTL lab was independently using live-cell and other microscopic brain-imaging techniques to study these systems in mice.

Using MRI, Reich’s lab scanned the brains of a group of healthy volunteers who had received injections of gadobutrol, a magnetic dye used to visualize disruptions in the blood-brain barrier. Kipnis’s lab injected mice with light-emitting molecules. Like with the MRI experiments, fluid containing these light-emitting molecules was seen to slip through the arachnoid barrier where blood vessels passed through.

Together, the labs found a “cuff” of cells that surround blood vessels as they pass through the arachnoid space. These arachnoid cuff exit (ACE) points act as areas where fluid, molecules and even cells can pass from the brain into the dura and vice versa, without allowing complete mixing of the two fluids. In some disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, impaired waste clearance can cause disease-causing proteins to build up.

“In the brain, clogs at ACE points may prevent waste from leaving,” Kipnis said. “If we can find a way to clean these clogs, it’s possible we can protect the brain.”

Reich and his team also observed more dye leaked into the surrounding fluid and space around the blood vessels in older participants, which may help explain why our risk for developing neurodegenerative diseases increases as we get older.