Maker in the Making

Bioengineer Uses Molecules to Study Diseases

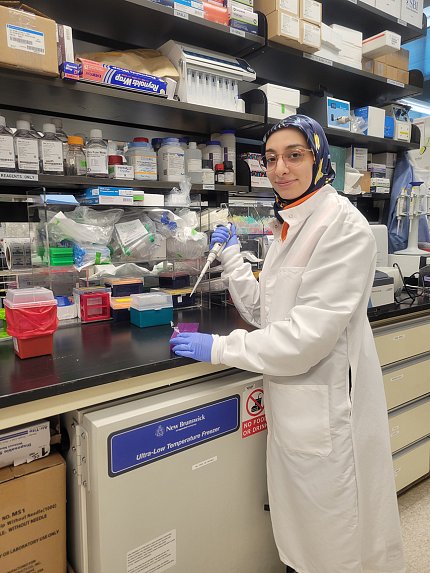

This mechanical engineer-turned-bioengineer is building her role as an NIH Maker.

In her unit for nanoengineering and microphysiological systems (UNEMPS) at the National Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering, Dr. Parinaz Fathi uses biological nanoparticles and miniscule organ models to study autoimmune disorders and cancer.

She received her undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering, but realized her interests leaned more toward biomedical fields.

“I liked my mechanical engineering classes but wanted [a career] with more immediate benefits to people,” she recalled.

Fathi went on to earn master’s and doctoral degrees in bioengineering and came to NIH as a postdoc in 2020. She began in Dr. Kaitlyn Sadtler’s lab, intending to start research projects in her chosen fields, but supply chain issues during the pandemic slowed her progress. In the meantime, Fathi spent time working on Covid-related research with Sadtler.

Fathi chose to see the delay as an opportunity rather than a setback.

“It gave me a chance to pivot and adapt to doing things that were more immediately relevant to public health,” she said.

She was able to return to her own research in time and progressed to independent research scholar in July 2022. She is now the principal investigator of her own lab, a goal she has worked toward since arriving at NIH.

Fathi’s lab is researching thyroid immune disorders through two avenues: studying nanoparticles and their communication with the thyroid and using microphysiological systems (MPS) to model the thyroid and its surrounding environment.

Biological nanoparticles called extracellular vesicles travel between cells and are used as a form of communication between them. Fathi is interested in how these nanoparticles might play a role in the development of thyroid immune disorders.

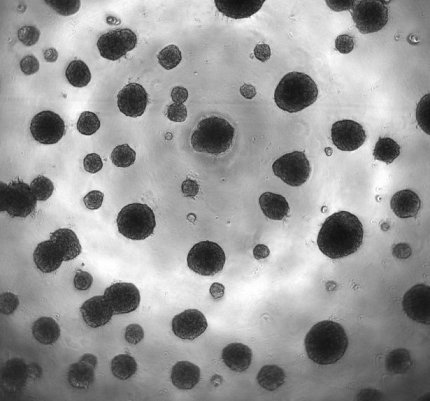

She also models the thyroid itself, by way of MPS. The technology allows her to mimic the thyroid’s biological environment on a small scale. She specifically develops “mini-organs” called organoids and spheroids to study how the conditions under which they are grown affect their morphology and functionality. Her end goal is to incorporate these models into more complex and physiologically relevant models in the future.

“We are developing these models…to study the thyroid immune microenvironment to better understand how diseases occur and maybe even come up with some new therapeutics,” Fathi explained.

Leading her own lab has come with other challenges outside of the science.

“I still feel that it’s a bit of a transition” almost two years in, she admitted, but the rewards are rich. Independent research scholars can mentor postbacs in their labs, and Fathi has a unique perspective as a mentor because she is not far removed from her own school days.

“I feel like I have an idea of what it takes to be a student and do research in different settings, and I think that definitely helps [relate to mentees],” she said. She is also still gaining insights from her own research collaborators and mentors at NIH.

“Everybody is constantly learning and we all have to be willing to adapt our mentoring styles and be open to learning new things.”