Zero in at Zip Code Level

Find ‘Actionable Targets’ in Diabetes Disparities Research, Egede Advises

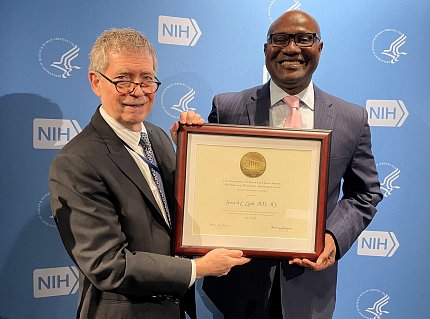

Nationally recognized health disparities researcher Dr. Leonard Egede recently visited NIH to deliver the 2024 Robert S. Gordon Jr. Lecture in Epidemiology. Egede develops and tests innovative interventions to reduce and/or eliminate health disparities for chronic health conditions. His talk—part of the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series (WALS)—focused on his diabetes research.

Diabetes is “a good marker for the work we do because of its prevalence,” Egede explained.

The condition affects about 15 percent of the U.S. population on average, but the burden of disease is unequal when broken down by racial group. Black Americans have the highest occurrence at 17%, followed by Asian Americans at 16% and Hispanic Americans at 15%. White Americans have the lowest incidence of diabetes: 13%.

What causes the disparity in disease burden? Egede believes social determinants of health (SDOH) play a role, and is researching ways to measure its effects. SDOH are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

Factors such as food insecurity, for example, can impact diabetes control through psychosocial factors such as stress, guilt, denial and other negative emotions—a phenomenon known as “diabetes distress.” Via this pathway, Egede found, food insecurity has a direct impact to glycemic control.

A significant marker Egede identified in evaluating SDOH is redlining, a discriminatory practice dating from the mid-1900s in which financial services were withheld from neighborhoods that have significant numbers of racial and ethnic minorities. Most marginalized populations in the U.S. still live in redlined areas today and feel its legacy.

Egede decided to use redlining as a surrogate measurement for structural racism in order to investigate the direct and indirect relationships between redlining and diabetes prevalence.

However, “we weren’t satisfied with [just] finding results,” he said. “We wanted to find…actionable targets.”

Photo: Diana Gomez

First, he and his collaborators reviewed the literature to see what had already been done. Once they had narrowed down their results, they saw that studies did show a measurable link between structural racism and poor diabetes outcomes. Individuals in these environments tended to have poorer clinical outcomes, such as higher HbA1C and blood pressure, worse self-care behaviors (diet and exercise), lower standards of care, higher mortality and more years of life lost.

Then, Egede conducted his own study to understand the impact of historical redlining and structural racism on diabetes prevalence.

Using a sample that was representative of all U.S. adults, he found that individuals in redlined neighborhoods were more likely to experience discrimination and/or be incarcerated, both of which can lead to poor health and disability.

He is currently studying the impact of structural racism on hospital closures in urban communities. There is an “absence of health care in inner city environments” that was worsened by the pandemic, he explained. He hopes to use his research to engage stakeholders to prevent future health care facility shutdowns, and help lower adverse impacts felt by communities that have experienced nearby clinic closures.

Egede wants his research to inform targeted interventions that address the direct and indirect pathways between structural racism and diabetes outcomes. Find the actionable targets, he advised, so “we can see what needs to be done at a zip code level.”

To view the archived lecture, visit https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=53833.