Youth with Conduct Disorder Show Differences in Brain Structure

Photo: GAO, STAGINNUS, ET AL., THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

A neuroimaging study of young people who exhibit a persistent pattern of disruptive, aggressive and antisocial behavior known as conduct disorder, has revealed extensive changes in brain structure. The most pronounced difference was a smaller area of the brain’s outer layer, known as the cerebral cortex, which is critical for many aspects of behavior, cognition and emotion. The study, co-authored by NIH researchers, is published in The Lancet Psychiatry.

A collaborative group of researchers examined standardized MRI data from youth ages 7 to 21 who had participated in 15 studies from around the world. The group analyzed 1,185 youth diagnosed with conduct disorder and 1,253 youth without the disorder.

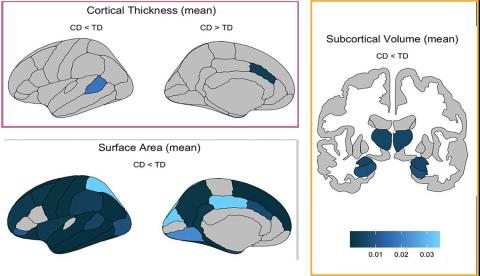

Youth with conduct disorder had lower total surface area across the cortex and in 26 of 34 individual regions, two of which showed significant changes in cortical thickness. Youth with conduct disorder also had lower volume in several subcortical brain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus and thalamus, which play a central role in regulating behaviors that are often challenging for people with the disorder. Although some of these brain regions, like the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, had been linked to conduct disorder in previous studies, other regions were implicated in the disorder for the first time.

Youth who exhibited signs of a more severe form of the disorder, indicated by a low level of empathy, guilt, and remorse, showed the greatest number of brain changes. The study also provides novel evidence that brain changes are more widespread than previously shown, spanning all four lobes and both cortical and subcortical regions.

“Conduct disorder has among the highest burden of any mental disorder in youth. However, it remains understudied and undertreated,” said Dr. Daniel Pine, chief, Section on Development and Affective Neuroscience, NIMH. “Understanding brain differences associated with the disorder takes us one step closer to developing more effective approaches to diagnosis and treatment, with the ultimate aim of improving long-term outcomes for children and their families.”