The Big Read

Mukherjee Provides Intimate Look at the Gene

Photo: Bill Branson

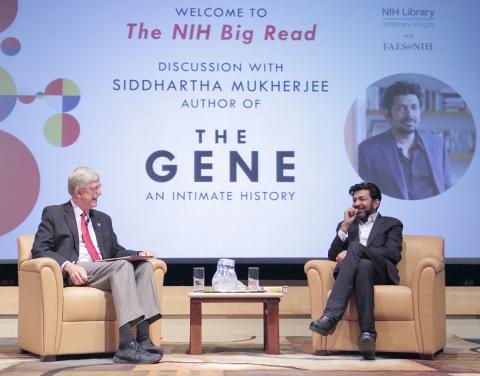

The best book discussions raise thought-provoking questions, spark lively debate and leave us grappling with profound subjects. So it was most fitting that the inaugural NIH Big Read featured Pulitzer Prize-winning author Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee talking about his latest book The Gene: An Intimate History.

Mukherjee, a cancer physician at Columbia University Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia, described the prospects of gene editing, which are both exciting and ominous, and leave many unanswered questions. Speaking recently to a packed Masur Auditorium, including many NIH’ers who attended the four book discussions at the NIH Library leading up to the Big Read, he followed up his presentation by joining an informal conversation with NIH director Dr. Francis Collins.

As a cancer geneticist, Mukherjee said he wrote The Gene as a prequel to his award-winning The Emperor of All Maladies. Understanding cancer, he said, requires understanding how cells behave and mutate. Writing the book also was a personal journey, given his family’s history of mental illness. Its first pages discuss his visit to a mental hospital in India to see his first cousin, confined for severe schizophrenia.

But it was Mukherjee’s fascination with emerging technologies that compelled him to write The Gene.

“I began to really think that the extent of these technologies to transform human beings and human culture vastly outweighed the kind of things we discuss in technology today,” he said. And it begs a critical question: “What do we do,” he asked, “when we can decipher and potentially change our own codes of instruction?”

Photo: Bill Branson

To frame the debate, Mukherjee put the sheer size of the genome in context. If the human genome’s 3 billion letters were printed in standard font, he said, it would span 70 sets of an encyclopedia. But the difference between you and a random stranger might amount to less than a book, and the relative difference between you and your sibling with a genetic disease might be just a couple of letters.

“If you had the capacity, as we now do, to select certain volumes or potentially change—going through that encyclopedia collection and go to page 373, volume 7—one letter to another letter, and do so in a way that might have permanence for human beings, the question is: would you do it, under what circumstances and what are the limits and constraints—scientific, social and ethical?”

The ability to add or subtract genes holds the promise of treating, if not curing, disease and alleviating human suffering, said Mukherjee. But editing genes also opens the door to such controversial issues as selective breeding, genetic enhancement and cloning.

“If you think more deeply about genes, you realize that…you could move some forward into next generations while eliminating, or rejecting others, and thereby lay the basis for a powerful method…to create better human beings.”

But history has shown a dangerous side of eugenics, from the late Carrie Buck, who was sterilized against her will in 1927 because it was believed she carried a genetic propensity for imbecility—and for whom The Gene is partly dedicated—to Nazi genocide.

“As we [move] forward with our enthusiasm for the new genetics or changing the human genome for selecting healthy, happy new children, eliminating genetic diseases,” said Mukherjee, remember that eugenics “in fact should remain as a line on our spines to remind us that this history is very recent.”

During his discussion with Collins, Mukherjee said, “It’s not clear to me at all that individuals will act in any interest outside the self-interest of bearing what they consider the best child, the most prosperous child they could have. The question that faces our generation now...is should we enter these waters and how deeply?”

Mukherjee said he predicts the first genetically enhanced human will be born in the next generation, with the experiment revolving around height. “I was not enhanced!” interjected Collins, to laughter.

Photo: Bill Branson

There’s a healthy dose of history and science in Mukherjee’s 500-page tome, but his writing style makes The Gene accessible. “The most important thing in [writing] a book like this is to remember that every page has to have a human story,” he told Collins.

Unlike The Emperor of All Maladies, which began with stories of cancer sufferers and later explained the science, The Gene puts the science up front. “You need the vocabulary to make it to the second half of the book,” he said, to get to the questions that reverberate outside of medicine.

“But if you put in too much scientific information, the most important readers of this book will be lost,” he said. “You don’t [want to] write a book that will sit in the library of a cancer center and never be picked up. I wanted to stimulate a conversation that was wider.”

As technology progresses, so must dialogue about the bioethics and boundaries of germline manipulation.

“I want us to think and pause before we move forward,” Mukherjee concluded. “I’m a physician, so the idea of the suffering of people, partly caused by genes—cancer is a great example—is not lost on me. The capacity to alleviate that suffering, as someone who belongs to a family where genes have played a disproportional and rather cruel twist, is not far from me. I remind people that my stakes in this are just as human as anyone else’s.”