History May Judge Harshly

End of AIDS Pandemic in Sight, Fauci Says

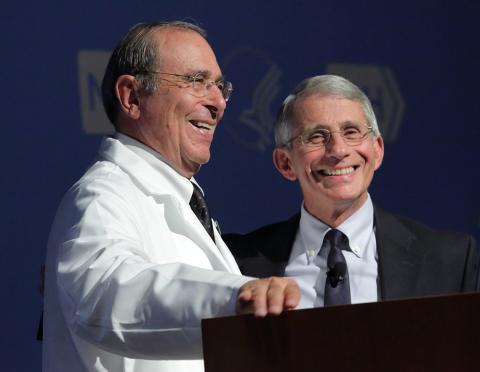

Photo: Ernie Branson

It is the global pandemic that has defined his life and career, and NIAID director Dr. Anthony Fauci says it is now within the realm of possibility that society can bring HIV/AIDS to a close, if we “follow the science.”

Speaking at Clinical Center Grand Rounds on the 35th anniversary of the first two reports about unusual infections killing gay men, Fauci credited NIH, and specifically its hospital, with having the latitude to let scientists drop everything and pursue a new field.

He reviewed “nothing short of breathtaking” advances in science since 1981 that have a made a historically unprecedented vista possible: a global infectious disease killing millions that is defined and corralled within a single generation.

But we are not there yet, he warned.

Fauci was working on the CC’s 11th floor when he read the first two articles in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, published within a month of each other, about a strange new disease affecting gay men in large U.S. cities.

“For the first one, I scratched my head,” he said. “I didn’t know what to make of it. I thought it might be some drug people were taking that affected their immunity.” The second paper “really changed the tenor of my professional career and life.”

Gradually erupting was a disease on a par with smallpox, measles and the flu. But as stunning as the research has been to define the virus and develop agents against it, there remains a stubborn level of HIV infection in the U.S. of 40,000 to 50,000 new cases annually that has persisted for the past 15 years.

“This is embarrassing and tragic and sad,” said Fauci. Of an estimated 1.2 million Americans infected with HIV, 13 percent are unaware they are infected; this population is responsible for transmitting about 30 percent of new HIV infections each year.

And the number of people who are diagnosed with HIV infection but are not being treated for it is responsible for transmitting more than 61 percent of new infections each year.

“We have a real implementation [of therapy] situation going on,” Fauci said. Botswana and Rwanda are managing their HIV burdens better than we are, he added.

“There is a degree of complacency in the U.S.,” Fauci said. “We really still have a major problem.”

Bearing the greatest burden of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. are young black men who have sex with men. “If you are a gay African-American, you have a 1 in 2 chance of HIV infection within your lifetime,” Fauci said. “That is a totally unacceptable public health statistic.”

Because June rounds lectures include so many summer students, Fauci’s talk served as both exhortation and history lesson. Here was an authority on hand in the early 1980s—when all 11 of the world’s experts on what was then known as GRIDS (gay-related immune deficiency syndrome) could meet on the sixth floor of the HHH Bldg.—and who now attends international HIV/AIDS gatherings involving 22,000 scientists.

Photo: Ernie Branson

When Fauci began seeing AIDS patients, most survived 8-15 months, he said. Today’s newly diagnosed 20-year-old patient, if he or she “follows the science,” can expect to live for 50 more years.

“That has to go down as one of the most transforming advances in the history of medicine,” said Fauci.

His formula for closing the curtain on the pandemic is founded on proven methods.

“Number one is test everybody,” said Fauci, and repetitively test those at risk of acquiring HIV.

Those who test positive follow a defined care continuum. Likewise, those who test negative follow a strict prevention continuum.

“Where we slip is in implementation of medical care that we know works,” he lamented. Only continuous therapy can affect the kinetics of the epidemic.

“There is no excuse whatsoever for not treating everybody,” Fauci said.

He described the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target for 2020 to end AIDS by 2030: 90 percent of all people living with AIDS knowing their status; 90 percent of those testing positive being on sustained antiretroviral treatment (ART); and 90 percent of those on ART having undetectable viral load.

If you follow that formula, 73 percent of all infected people would have an undetectable viral load and the trajectory of the epidemic would decrease dramatically, Fauci said, but globally we are only at around 32 percent. Botswana is now at 70.2 percent. “We can do better than that,” Fauci insisted.

But the fact that 1 in 3 primary care physicians in the U.S. have not even heard of pre-exposure prophylaxis dampens Fauci’s optimism.

“There really are no more excuses,” he said. “We are never going to be able to eradicate HIV, but we can end the epidemic as we know it.”

His current faith is bolstered by fresh scientific advances in several arenas—toward an HIV vaccine, the promise offered by new gene-editing techniques and efforts toward a “cure,” which really means an effective way to address viral persistence. A cure, he emphasized, would have to be simple, safe and scalable. “You would have to treat people very early in order to control viral rebound. However, right now, if you discontinue therapy, virtually all patients rebound.”

As for vaccines, he said, “There are some really very interesting approaches, but you have to remember that this is one of the most daunting scientific challenges we have ever faced in the field of vaccinology.”

The kind of vaccine that worked so well for polio, measles, mumps and smallpox by mimicking natural infection is not going to work for HIV, Fauci explained. A different approach involves understanding the physical features of the virus so well that vaccines could be developed that properly engage the B cell lineage and induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV.

“It may be that we will need sequential immunizations to coax along the immune response,” said Fauci. Whereas the measles vaccine is 98 percent effective with a shot at age 1 year and again at age 4 to 5 years, “we are not going to get that with HIV,” Fauci said. He concluded, “I think maybe 50 to 60 percent vaccine efficacy is within our purview.

“We have followed the science to where we are now. We do have the tools, but we need to implement the science, and do more science and discovery to reach a durable end to the pandemic.”

He continued, “We have the opportunity of being the generation that was there when the disease was first recognized, and we could be there when it is over. That has never been done before with a disease of this magnitude. I believe that history will judge us harshly if we do not take advantage of that opportunity.”

The full talk is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=19231&bhcp=1.