Supported by NIH Interpreters

Deaf NCI Fellow Wins Awards for Research Presentation

Megan Majocha, a Ph.D. student in tumor biology in the NIH-Georgetown Partnership Program, received a travel scholarship to present her findings at the International Mammalian Genome Society Conference (IMGC) in Vancouver. She works in Dr. Kent Hunter’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics at NCI, where they use integrated genetic and genomic technologies to better understand the heredity factors that contribute to the metastatic progression of breast cancer.

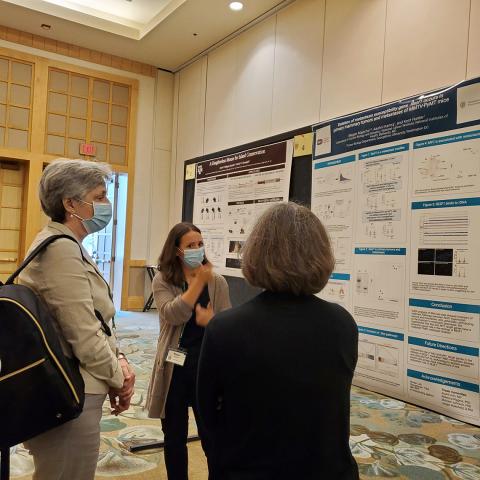

Majocha, who is deaf, requested that her team of scientific interpreters who are familiar with her research and signing style, accompany her to the IMGC. A partnership between the Office of Research Services and NCI made it possible for her to present her findings at the conference with her team of NIH interpreters. She won the Lorraine Flaherty Award for outstanding presentations at the Trainee Symposium. This award, given to the top three presenters, provides the opportunity to present at the plenary session. Her presentation there won her a second award for most outstanding talk.

“My thesis focuses on one understudied gene RESF1 and its role in suppressing tumors in ER-negative metastatic breast cancer—a less common type of breast cancer that’s more challenging to treat and has poor treatment outcomes,” explained Majocha in a recent chat with Linda Kiefer, manager of ORS’s interpreting services program. “Understanding this gene could lead to better treatment outcomes for these patients.”

In 2018, Majocha began as a post-baccalaureate fellow for 1 year in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics. Afterwards, she completed a few other training rotations before returning to Hunter’s lab as a Ph.D. fellow. IMGC was her first in-person conference as a graduate student and the first time she presented her work in front of fellow researchers.

“It provided me with the opportunity to network with others in my field,” Majocha said. “Having my interpreters there allowed me to listen to other presentations, participate in discussions and contribute to the daily conversations…which was the highlight of the conference experience for me!”

Interested in science communication, Majocha eventually hopes to find ways to share her research with the public, making it accessible and easy for anyone to understand.

“The Deaf community gets most of its information through ASL [American Sign Language],” she said, “and we need to communicate science in English and ASL in ways everyone can understand and receive equal access to information. We need more ways to share information through social media, and I want to help make those connections. At the same time, I want to pursue my cancer research where it leads.”

That’s one reason having her NIH interpreting team at IMGC with her was crucial.

“I have been working with my interpreting team for several years,” she said. “They know my signing style and understand my research conceptually. Even an experienced STEM interpreter might not be able to grasp what I want to say without being thoroughly briefed and/or having spent time with me in the lab.

“It’s different with ASL, which has standard signs making it easier for them to interpret even for someone they don’t know well,” she continued. “But scientific and technical terms don’t have standardized signs. Sometimes we make them up as we go, specific to our lab. Having to worry about how well the interpreter is interpreting what I am saying is a huge distraction from my presentation; that’s why I prefer to bring my own. I’ve spoken to other deaf scientists who say they’ve had to lower their expectations and settle for what they can get. Others have given up the struggle and avoid conferences altogether. I don’t think we should settle and encourage them to advocate for themselves and all of us in the Deaf community.”

Early in her science career, Majocha experienced what it’s like not to have the same access as her hearing peers.

“As a freshman, during my first summer research internship, I wrote notes back and forth to communicate with others until I learned how to advocate for myself,” she recalled. “Many of my graduate courses were audio-taped and shared with the class, which wasn’t useful to me as a deaf student. So, I started asking my professors for transcripts of the audio, which they were willing to provide. The turning point for me was when I had to practice my oral presentation with slides in front of my professor, without an interpreter. I had arranged for one, but he was too busy to wait for the interpreter to show up. So, I signed my entire presentation to someone who didn’t understand ASL. That was one of the most awkward and humiliating experiences I have ever had, and it was of no benefit to him or me—except I learned that advocacy was key to improving access.”

Majocha said other science-minded organizations can learn a lot about accessibility from her workplace.

“The interpreting program at NIH is among the best programs anywhere,” she said. “NIH provides top quality STEM interpreters that are easy to access on demand. My NIH interpreters understand NIH culture and Deaf culture. They have enabled me to be me, and because of that I’ve been able to get accepted into top graduate programs. This is one of the primary reasons I came back to NIH to do my Ph.D. program. Here, I don’t have to fight to be heard.”

NIH’s interpreting services program has been serving the community for more than a decade. It provides centrally funded, reliable and easy-to-access services for patients, visitors and the NIH workforce.

“Overall, the interpreting services NIH provides is top quality,” Majocha concluded. “One ask would be to provide more STEM interpreters so there are enough to go around. Even at Georgetown, there aren’t enough. It would be great too if scientific interpreters could get some formal STEM training to establish some standard signs.”