‘Bring It On! I’m Ready’

CSR Division Director Hit the Ground Running

It’s never too late to make a healthy lifestyle change. One motivated NIH’er turned his personal fitness challenge into a hobby he loves—one that truly cured what ailed him.

When Dr. Dipak Bhattacharyya was in his early 40s, he knew something had to change. He was sedentary, fatigued and highly diabetic.

“Being a scientist, I tended to spend so much time in the lab doing research and didn’t figure out I needed to take better care of myself,” said Bhattacharyya, a biochemist by training who formerly worked in an NCI cancer lab and later moved into information technology. He currently is director of the Division of Planning, Analysis and Information Management at the Center for Scientific Review.

Bhattacharyya decided to try running. But on his first outing, he only had the endurance to run a quarter mile.

“Running became a challenge to me,” he said. “I started gradually, running a little bit every day, and in a year went up to 15 miles over each weekend. I started liking it and seeing the health benefit.”

In 2014, his children encouraged him to try running a marathon. That year, at age 51, he ran his first marathon.

“I’m an achiever type,” Bhattacharyya said. “If I’m sticking to something, I want to see it to the end.”

But it didn’t end there. Not long after his first, he began running a marathon a month. Unsurprisingly, he enrolled in a club called Marathon Maniacs and eventually was running a marathon per weekend.

Next, Bhattacharyya ran a 50-miler and, on Dec. 31, 2016, he attempted his first 100-mile run: the Pistol Ultra in Tennessee. Racers had 30 hours to complete it, and he finished.

“The beauty of these ultramarathons is they offer support,” said Bhattacharyya. “Every 6-10 miles, we’ll get water and food.” But after running numerous ultramarathons with such support, he decided it was time to kick it up a notch.

“I wanted something even more challenging with no one to support me, where I had to figure it all out for myself,” he said. So far, he has finished more than 120 ultra races, many of them with no support, where runners carry their belongings and find their own food, water and lodging.

It’s fair to say Bhattacharya has become addicted to running and the resulting health effects. While running keeps him physically fit and reinvigorates his mind, he also has experienced another profound health change.

“Running took care of my diabetes [type 2]. It’s completely gone. I’ve been diabetes-free for 15 years,” said Bhattacharyya, who also made dietary changes and is now vegan.

“The good thing about picking up healthy habits is you gradually expand,” he said. “Because I already achieved this goal, I think: what’s the next thing?”

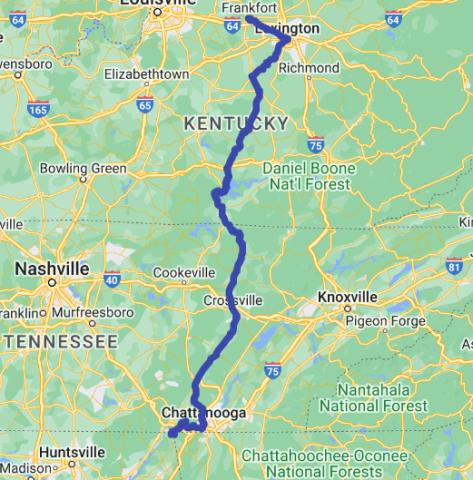

That next thing was a whopping 328-mile run in June that started in Kentucky. This run—the Heart of the South—traverses the Tennessee mountains. It’s so hot that runners pound the pavement at night and rest during the day.

“I was trying to discover myself, what I am made up of, whether I can really do this,” said Bhattacharyya, who was selected in a lottery for the race. “The major problem was the heat…It’s so hot. You get many blisters; your feet hurt. It’s very, very challenging. So I wanted to do that!”

Another major challenge was planning to stay fed and hydrated. Runners have 240 hours to complete the run. Barring an emergency, there’s no support and runners initially have no idea what they’re getting into.

“The beauty of this run is they won’t tell you anything in advance,” he said. “You don’t know the course. You park the car at the finish line. A bus picks you up. They put you in a hotel the night before and give you a map.” Then, runners fend for themselves back toward the finish line.

The run began with 90 people; 56 completed the race. Bhattacharyya was one of them, finishing in the middle of the pack.

One day, his 3-liter bottle leaked in his backpack and all the water had drained out. He was 23 miles from his motel and 8 miles from any place selling drinks. Mercifully, a driver going by saw him and, without a word, sped off and returned with a bottle of water and a Gatorade.

On the trail, up and down the mountains on the highway shoulder, the asphalt scorching hot, he would run all night, rest a few hours, shower, pick up a sandwich and forge on for the next 40+ miles.

“I learned through this process that the human body is extremely powerful,” he said. “You can do anything with your mind.” Despite the intense heat, thirst and hunger, “I was able to handle it.”

And he wants to do it again. “Bring it on! I’m ready,” he said, having put his name into the lottery, and gotten accepted, to run Heart of the South, summer 2023.

Now 58 years old, Bhattacharyya still runs 10 miles every day and tries to inspire others to run. He encourages colleagues to participate in NIH runs and relays and has even persuaded a few to try running a marathon.

“I’m not telling everyone to run 350 miles,” he said. “Run 2 miles a day or 1 mile. It will change your life. It changed mine.

“You just have to make the time. When you begin a fitness journey, it will become second nature, like breathing. Running has become such a part of my life that I feel tired if I don’t go out and do it.”