Perspective Matters

Rare Cancer Survivor, Oncologist Discuss the Patient Experience

Frustrated. Isolated. Angry. Anxious, yet determined and hopeful. These are among the many emotions experienced by patients with rare cancers. Deanna Fournier knows firsthand.

Fournier was just 6 years old when she was diagnosed with a rare cancer. The prognosis was bleak, but she survived. Looking back, “I had to grow up rather quickly,” said Fournier, director of the Histiocytosis Association. She shared her journey at a recent NCI Office of Cancer Survivorship lecture that also featured Dr. Eli Diamond, a neuro-oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The symptoms Fournier had experienced—back pain, prolonged constipation, difficulty walking and a droopy eyelid—were not necessarily indicative of rare cancer. But when symptoms didn’t improve, doctors took a biopsy of a lesion on her spine and diagnosed her with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Looking back, “I think about the feelings my parents and I felt, this burden of navigating this journey alone, [of a disease] we had never heard of before,” said Fournier. The uncertainty was terrifying. Would treatment work? What quality of life would she have?

Fournier’s family contacted a doctor who offered the most advanced treatment available at the time, but they faced a distressing choice. The new treatment “possibly would be incredibly toxic and lead to negative outcomes,” she said. Fortunately, she had a positive outcome.

“But the journey doesn’t end when the disease goes into remission,” said Fournier. She continued experiencing mobility challenges and inflammatory responses to certain stimuli. The threat of relapse loomed. There are still many unanswered questions.

“Sometimes we don’t even know what questions to ask,” she said, “and we’re afraid of asking too many, fearful of the burden on our care partners, our family and friends.”

As with any rare cancer, the burdens are tough to navigate, from chronic pain to anxiety over treatment cost to the lack of information and resources.

“Patient research can really help with this so we can better understand all the gaps and challenges in the patient journey,” she said.

That’s what Diamond has come to work on—partnering with rare cancer patients and their caregivers to help manage the burden of living with rare cancer—while researching treatments for these diseases.

Photo: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

“I want to emphasize that, while individual rare cancers are of course rare, in aggregate, they are not rare,” said Diamond. “Probably about one in five individuals with cancer has a rare cancer, so what we learn about a single rare cancer really reverberates to other affected individuals.”

Histiocytic cancers (HC) are blood cancers caused by an excess amount of histiocytes—a type of white blood cell—within tissues. Symptoms are severe.

LCH, the kind that afflicted Fournier, can affect different organs—liver, lung, spleen—as well as lymph nodes, skin and bones of the spine and hips.

“I cannot overstate this,” said Diamond. “This disease can cause the most excruciating pain in all types of areas—the mouth, the groin, the skin, all over. It can be dreadful.”

In milder cases, affected areas can be surgically removed followed by radiation and observation. In more severe LCH cases, before gene-targeted therapies were discovered, chemotherapy was curative for some. Others needed many lines of chemo over years; a fraction went into remission.

Diamond focuses primarily on patients with another HC called Erdheim-Chester Disease (ECD), a multi-system disorder that’s also extremely painful. ECD causes tumors in the legs, organ dysfunction and uncontrolled inflammation, and often a range of neurological symptoms.

Research advances have led to newer medications—some with FDA approval and others in clinical trials—to help manage symptoms, though they come with serious side effects.

One such drug called Cobimetinib, approved by the FDA in recent months, worked wonders in almost all patients but side effects included heart problems, gastrointestinal issues, body rash, muscle problems and fatigue. For another approved drug, a third of patients in the clinical trial had to stop taking it due to intolerance.

Medications are “halting mortality, on the one hand, but have very difficult side effects on the other,” said Diamond. Only a tiny fraction of patients are cured without enduring effects. For most people, stopping treatment leads to relapse. “So it’s acting like an off switch, but it’s not a cure.”

And that is the conundrum, Diamond noted. “Many patients with these diseases now have this managed but incurable, chronic illness, balancing suppressing their disease on the one hand and side effects on the other.”

To better understand the burdens and challenges of rare cancer patients and their caregivers, Diamond started a registry for ECD patients.

“We on the clinician-scientist side came up with 27 symptoms that patients with this disease could possibly have,” said Diamond. After reviewing patient responses from focus groups and interviews, they ended up with more than 60 different symptoms.

Learning more about the array of symptoms has helped Diamond advocate better for his patients.

“Being able to report the frequency and severity of disabling pain and fatigue has allowed me to secure disability benefits for patients even when they don’t meet the conventional criteria,” he said.

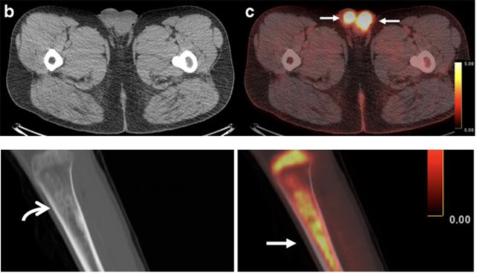

The registry also helped highlight the importance of PET scans—which detected almost every tumor—in fully evaluating and treating patients.

Diamond’s team then did a deeper dive with a subset of patients, conducting more detailed surveys and interviews.

“Patients in the study always said fatigue and pain were co-travelers,” he said. They described their fatigue as intrusive and exhausting; every little thing takes effort. The pain is “electrical.”

Further, he said, “it was sobering to learn that whether someone’s disease was in remission or what kind of treatment they were on did not have any association with more or less frequent pain.” The chronic symptoms make palliative care especially important.

“In the cancer caregiving world, [a vital coping factor] is how individuals are able to find meaning and purpose in the experience of providing care,” Diamond said.

A study his team conducted of 92 caregivers to patients with ECD and other histiocytic disorders revealed most of the caregivers had one and often multiple unmet needs, from resources to emotional support.

It’s a vicious cycle. The lack of information and expertise about the rare disease leads to unmet needs for the patient and caregiver, while both must navigate long-term symptom management amid an uncertain future. All of it creates “this unfortunate loop of decreased meaning and purpose” and rising anxiety for the caregiver.

“We need more longitudinal studies to test interventions to help incorporate patient-reported outcomes into trials, more symptom-directed interventions themselves,” as well as more informational and social support for caregivers, said Diamond.

“There is hope on the horizon,” added Fournier. “We have gratitude for the dedicated clinicians and researchers who are adamant about getting us ever closer to a cure.”

To view upcoming lectures in the series, see: https://bit.ly/3De7zg1.