Science Stays Center Stage

After 50-Plus Years, Gallin Steps into Next Phase

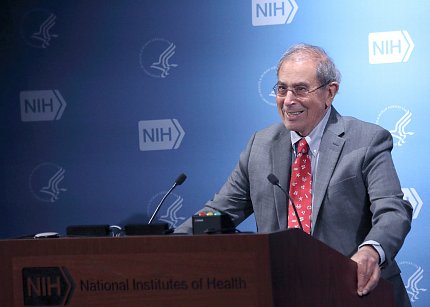

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

From an early age, John Gallin gravitated toward a career in science. He was five years old when he spied a garnet stone, about the size of a half dollar, on the ground. He’s been fascinated with the structure of crystals ever since. Instead of mineralogy and the study of gems, however, it’s been medicine and clinical research that captured both his heart and mind. He pursued research in microbiology and clinical research as a medical student at Cornell Medical College (now Weill-Cornell).

On Mar. 25, his 80th birthday, Gallin stepped into a new phase of the career into which he invested more than a half century: He retired as NIH associate director for clinical research and chief scientific officer of the Clinical Center (CC) in route to designation as a scientist emeritus.

“The bottom line is that for me, it’s the patients,” he said. “Ask me what’s most special about NIH? It’s the ability to work with the patients and then have the luxury of doing the science as it relates to trying to make things better for them.”

After an internship and residency in internal medicine at NYU-Bellevue Hospital, Gallin first arrived at NIH in 1971 as a clinical associate, to get training in infectious diseases and research in the NIAID laboratory of physician-scientist icon Dr. Sheldon “Shelly” Wolff.

“I fell in love with the clinical research,” explained Gallin. “I came to an environment with tremendous mentors and colleagues, who exchanged scientific information and developed lasting friendships. We didn’t have to worry about how we were going to get our next dollar to support our research or patient care. We could bring in patients as scientific opportunities arose. We had the Clinical Center where we could provide outstanding care while conducting our clinical research.”

In early days at NIH, Gallin encountered the fellow physician-scientist who would become one of his closest associates—retired NIAID director and President Biden’s former chief medical advisor Dr. Anthony S. Fauci. They first met outside their respective labs in the Clinical Center and became not only scientific colleagues and confidantes, but also best friends away from NIH.

“There are so many happy moments that I associate with my 51-year friendship with John Gallin,” said Fauci. “One is that for as long as I can remember, every year my wife Christine and I shared a quiet New Year’s Eve dinner with John and Elaine where we would reflect on the accomplishments and challenges of the prior year and our hopes for the coming year. Another is when John and I go fishing together—too infrequently. He almost invariably catches more fish than I do…One time, I hooked what was probably a rather large fish and I yanked the pole so hard that I tipped over our canoe and we both found ourselves swimming in the Potomac River.”

After three years of training, Gallin left NIH in 1974. He’d been named senior chief medical resident at Bellevue Hospital at New York University. In 1975, he promptly returned to NIH for good. Over the course of five decades here, he’s seen remarkable breakthroughs in clinical research, particularly in his own field of study.

“Advances in immunology and understanding how the immune system works to defend us against infections have been dramatic, resulting in the vaccines that you’ve heard about—most recently, the Covid vaccine, but before that, the Ebola vaccine, and improvements in other vaccines,” he observed. “Another big advance—the ability to modulate the immune response against diseases that cause inflammation, like autoimmune diseases, has been nothing short of dramatic over 50 years, enabling patients to live better lives…helping us to understand new diseases.”

Science itself and the biomedical research enterprise have evolved in that time as well.

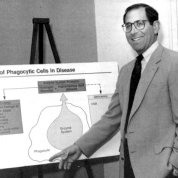

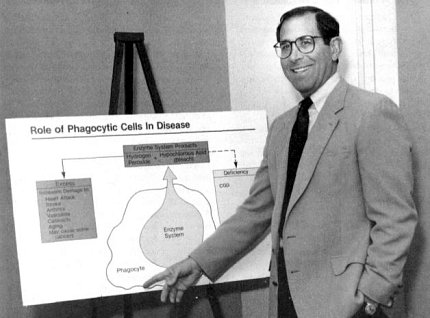

“When I started my clinical research at NIH, Shelly Wolff suggested I focus on patients with disorders of phagocytic cells—neutrophils and monocytes,” Gallin pointed out. “We defined the clinical phenotype and molecular abnormalities in these patients. Our group described new molecular deficiencies in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood (CGD), but also discovered IRAK deficiency, neutrophil-specific granule deficiency, the molecular basis for the lazy leukocyte syndrome—an actin dysfunction disease—and Job’s syndrome of hyper IgE and recurrent infections. Being able to understand the genetics of diseases, which came later, is just a huge advance…the biochemistry of the diseases and understanding exactly what molecules are abnormal. Then, designing interventions based on the scientific knowledge, including bone marrow transplantation and gene therapy, has resulted in clinical cure of some patients.

“In science today,” he continued, “when somebody comes in the lab as a young person, they can get a very clean, specific answer to a question at a very precise level, much more finely tuned than we could before. And that’s wonderful, because then you can think about interventions.”

Dr. Maureen Gormley, former NINDS deputy director for management, met Gallin in the early 1990s when she was a CC assistant hospital administrator and he was NIAID scientific director. She became his special assistant when he was appointed CC director.

“He helped my career flourish,” she recalled. “Dr. Gallin is a highly disciplined, hard-working and visionary physician- scientist. His leadership inspired me and our whole team to fully commit ourselves and always look for ways to improve the hospital for patients and investigators. [He] also is a caring mentor who invests significant effort in developing the careers of all members of his team.”

In a 50-plus year NIH career, Gallin has served as NIAID lab chief and scientific director for nine years; CC director for 22 years and for the last six years CC chief scientific officer; and for 28 years NIH associate director for clinical research.

At 22 years, his directorship of the Clinical Center is the longest in NIH history. Of course, there were challenges as well as triumphs. Funding, staffing and oversight were all examined thoroughly by insiders and outsiders, with Gallin steering the largest research hospital in the world through storms and calm waters.

Some of his proudest achievements include creating the Patient Advisory Group; helping to construct the first Clinical Research Information System and Biomedical Translational Research Information System that combine patient information into a common database that scientists can access; and building the first bioethics department, which Gallin said “has really flourished.”

He and his CC team were also instrumental in opening the doors of the Clinical Center to the extramural community. They created “Bench to Bedside and Back Awards” and other mechanisms to usher projects between basic science and clinical activity.

In addition, he focused on education and training in his tenure as CC leader.

“We built a curriculum in clinical research that started as a seminar with 15 students and today is reaching 25,000 students a year and over 160 countries throughout the world,” he said. “To watch that grow and to see some of its impact has been very satisfying.”

Gormley noted, “Over the 22 years we worked together, Dr. Gallin led the Clinical Center through countless remarkable events including the planning and activation of the new Clinical Research Center, the creation and opening of the Safra Family Lodge, construction of a dedicated campus entrance for patients and installation of modern electronic medical record and integrated patient scheduling systems. He ran command centers in response to furloughs, floods, fires and blizzards. He hosted presidents, politicians, world leaders and entertainers. In 2011 he accepted the Lasker Bloomberg Public Service Award on behalf of the generations of clinical researchers who contributed to the legacy of accomplishments at the Clinical Center.

“One of the most significant memories I have of his leadership was his steadfast focus on the patients, their care, their safety and the ways in which he developed services, like a huge reception desk at the entrance of the Clinical Center to make them feel welcome and to ease their fears,” Gormley continued. “Dr. Gallin’s leadership style is a seasoned blend of humility and humanity. His legacy will be long remembered.”

Clinical Center CEO Dr. James Gilman, who succeeded Gallin at the CC helm, agreed, “As one might expect from someone with my military background, I am very much unaccustomed to seeing organizations thrive under the same leader for 22 years as the CC did under Dr. Gallin’s leadership. I felt that way when I arrived on the scene in 2017. If anything, I am more amazed at his achievements now than I was then.”

In the last few years in his post in Bldg. 1, Gallin was able to take a bird’s-eye view of NIH’s clinical research enterprise. He helped build the scientific review process for all clinical protocols and expanded data sharing through clinicaltrials.gov. He made data sharing plans a requirement in the clinical protocol scientific review process he developed.

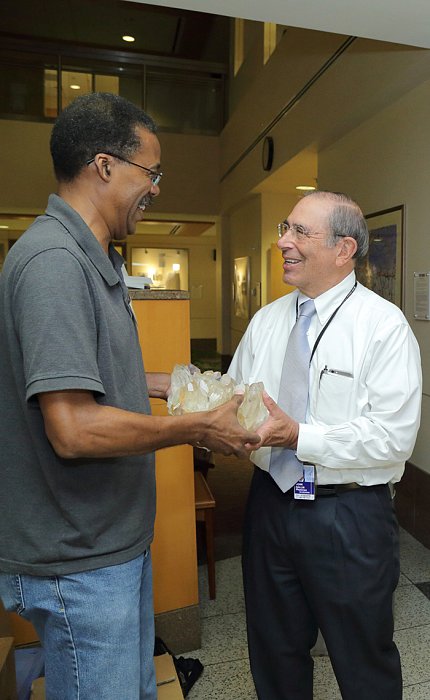

Photo: Ernie Branson

In essence, the enchantment with crystallography that started Gallin’s scientific pursuits never faded. In fact, he managed to combine his love of minerals with his day job. In 2016, he orchestrated a collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution that installed a “Minerals in Medicine” exhibit in a corridor of the Clinical Research Center. The installment is now permanent.

As he began life as a retiree, Gallin recommended that his successor focus on inspiring and nurturing would-be investigators of the next age. And he’s ready to help, because he fondly recalls that 5-year-old who picked up a shiny rock and followed a path of discovery ever after.

“We need to be very sensitive to young people,” he concluded. “We have to make sure we have an environment that cultivates the next generation of scientists and clinical investigators, so that it’s optimal for them to succeed.”