Rizzi Appeals for Accessible, Usable, Functional Digital Environments

Much of the digital world is inaccessible to people with disabilities, said Albert J. Rizzi, during the final DDM Seminar of 2023. That prevents them from living their life to the fullest.

“When we make things universally accessible and usable for people with disabilities, we wind up making it a better place for people of all abilities,” said Rizzi, founder and CEO of the My Blind Spot, a non-profit that ensures digital environments are accessible, usable and functional for people with disabilities.

Rizzi is one of the 62 million Americans living with a disability. In 2006, he contracted fungal meningitis, a rare, life-threatening infection that causes swelling of the areas around the brain and spinal cord. As a result of the infection, he lost his vision. It could’ve been worse.

“I could’ve been blind, deaf and paralyzed,” he said. “Only being blind was a good thing.”

Until then, he didn’t know any other people with blindness. He only knew of celebrities with vision loss, such as Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Helen Keller and José Feliciano. He quickly realized he had to overcome digital barriers.

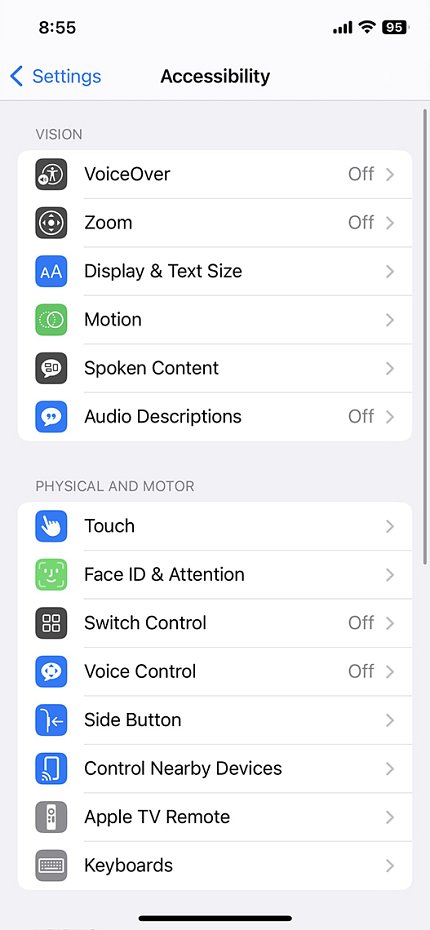

“I had to learn a whole new way of navigating the internet,” he said. “I have a computer that talks to me called a screen reader. Unless the world is coded that way, I can’t access anything, ostensibly disabling the world to me.”

Additionally, he faced “low expectations about his ability.”

Rizzi was an accomplished business owner and educator, but, once he lost his sight, he became “persona non grata.” He was told he’d never work with children or be an executive again. “Nothing about that made me feel good about being blind,” he recalled.

Rizzi’s parents didn’t raise him to give up. So, he started his non-profit to advocate to “make sure the digital platforms we’re inextricably tied to in the 21st century work seamlessly” for people with disabilities.

People with disabilities need support, not sympathy. Everyone—whether disabled or not—has their own challenges and limitations. If people with disabilities are given reasonable adaptations and held accountable, Rizzi believes more of them will be visible at school and work.

“Going to work cures so many ills,” he said. “It improves our mental health, makes us feel like valued contributors and gives us a reason to wake up in the morning.”

Telework during the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that working from home is a way of life, not a reasonable accommodation for people with a disability. As much as 50% of work can be done remotely.

“That is opening up avenues to employment and academic enrichment for the disability community like never before,” he said. “We need to challenge our design and development teams to make sure our platforms work.”

Accidents and unexpected illness are the leading causes of disability, he said. Just about everyone will join the disability community at some point in their lives. Learning to live with a disability is traumatic, but it’s not a life-ending event.

Some members of the public believe that people with disabilities “need assistance all the time.” This view prevents them from becoming independent taxpayers. In many cases, however, they just need access to the right tools “to promote their ability and allow them to create and restore infinite possibilities.”

Rizzi challenged companies and academic institutions to perform “disability-friendly audits” to identify ways to make technology and physical locations more accessible. For instance, could a person with a mobility impairment take their identification badge and hold it up to an access reader? Or are rooms clearly defined with Braille?

There are benefits to committing to making a workplace disability-friendly and ready. Including people with disabilities in the workforce improves morale and competition and increases brand and image awareness.

“We need to let people with disabilities rise to the heights of greatness,” Rizzi concluded. “We need to support them as individuals and we need to demand it in our society.”