CC Epidemiologist Takes Note

What We Learned from Covid Response

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted both strengths and weaknesses in our public health infrastructure and beyond. What can we learn from it? And how can we use it to prepare for future threats?

Former Clinical Center hospital epidemiologist and 41-year NIH veteran Dr. David Henderson recently took the (hybrid) stage to deliver what he called “the gospel according to Henderson,” or his assessment of the U.S. response to the 3½-year health crisis. His talk, “The Covid-19 Pandemic: Looking Back and Looking Forward,” was a recent installment in the Contemporary Clinical Medicine: Great Teachers lecture series.

Henderson opened with what appeared to be a familiar scene: a graph showing the progression of viral cases over time. “[This is] the kind of epi-curve most of us sweat bullets over in the last 3 years,” he said.

In this case, however, the virus in question was not Covid-19, but the 1918-19 flu.

Just over 100 years prior to the pandemic of our time, this public health situation looked very similar: 675,000 people died in the U.S. alone and health care workers urged people to wear masks to limit the spread of disease.

Covid “seems like déjà vu all over again,” Henderson said. About one-third of Americans have had documented infections, and the death toll at the time of the lecture stood at about 1.17 million people in the U.S. alone. Henderson expressed incredulity at the numbers.

“Consider this,” he said. “In a time when science and medicine have made astounding diagnostic, therapeutic and preventative interventional strides, we did not fare much better in the Covid pandemic than we did in 1918, when we didn’t have diagnostic tests or any therapeutic interventions other than supportive care.”

This is not to say that there were no triumphs in our Covid response, Henderson acknowledged. Vaccine development was an “astounding success” in many aspects.

The virus was sequenced on Jan. 12, 2020, and the first vaccine emergency use authorizations (EUA) were issued on Dec. 11 and 18 of that same year. There were also numerous platforms for the vaccines, from the familiar protein subunit and adenovirus vector to the new and incredibly successful mRNA vaccines.

Finally, the vaccines themselves were safe and effective, and still provide protection from severe disease and death as new Covid variants continue to evolve.

But, as Henderson’s Covid/1918 flu comparison showed, the U.S. still has many opportunities for improvement. Many of these problem areas “could have been obviated by availability of aggressive testing, contact tracing and quarantine,” he said.

The first at-home test kits were not approved until November 2020. In the meantime, states and municipalities scrambled to implement rapid, widespread testing efforts. Health care workers also ran into difficulties obtaining personal protective equipment (PPE), especially masks and gowns.

The Strategic National Stockpile, which was created in 2006, had limited PPE inventory and could not distribute enough supplies to states beyond the first three months of the pandemic.

Henderson said, public health infrastructure in the U.S. is “antiquated, understaffed, under-resourced, under-incentivized and [in need of] revitalization.”

Only 187 health care facilities reported electronically to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the start of the pandemic. That number has risen to 25,000, but still only accounts for one-quarter of health care facilities in the country.

Our public health systems are “light years behind where they need to be,” Henderson estimated.

He said misinformation and poor communication also played an outsized role in the country’s pandemic response.

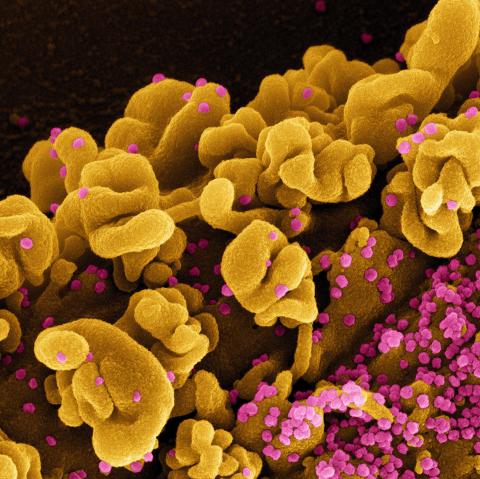

Photo: niaid research facility fort detrick md

One early example was the mixed messaging over mask recommendations. Masking was initially discouraged for the general public in order to save supplies for health care workers, with the recommendation changing in early April 2020. That “likely set us back a bit,” said Henderson.

The thorny issues of politics quickly became entangled in pandemic policy as well, to the detriment of public health. Public figures downplayed the severity of the virus, cast doubt on the efficacy of masking and social distancing, expressed support for conspiracy theories and unproven treatments and shared inaccurate information about side effects of Covid vaccines.

Henderson wants to “get everyone on the same page—we’re all facing the same foe.”

Some effects of the pandemic response may be here to stay: working from home, source control masking, hand hygiene dispensers, individualized risk assessment and focus on vulnerable populations. These changes are for the better, Henderson said.

Experts agree that Covid will not be the last pandemic the world faces. How can we prepare for the next one?

Start with a federal government-led response, Henderson said. The response should be centralized and coordinate with state and municipal health departments. The public health system should also be well-funded and equipped to handle the strain of a prolonged pandemic response.

Transparency is of the utmost importance; communication with the press and the public should “[emphasize] the difference between what we know and what we think,” Henderson said, noting that this was a point of weakness in the U.S. Covid response.

Additionally, the response should balance between protecting health while still minimizing disruption to normal societal functioning. It is better to begin with more restrictive policies and be able to relax them later, Henderson opined.

He also emphasized institutional preparedness. Most pandemic preparedness plans were developed from H1N1 and the 2003 SARS outbreak, and need to be updated with new knowledge from Covid.

During the 2014 Ebola epidemic, for example, the Clinical Center staff created a pandemic response plan for treating a symptomatic patient.

“We drilled with [a mock patient]…and met every afternoon at 3 for a month or two describing what went right and what went wrong,” Henderson explained.

“We were very prepared” to keep immune-compromised CC patients safe while treating symptomatic Ebola patient Nina Pham in October 2014.

There are still lingering societal complications for which Henderson has no solution, he admitted. Science denialism, anti-vaccine sentiment and extreme politicization are more hurdles that must be addressed to successfully weather future pandemics.

As British chemist and X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin once said, Henderson quoted, “Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.”

The archived lecture can be viewed at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=49891.