The Way Science Thrives

Former NIH Molecular Biologist Singer Remembered

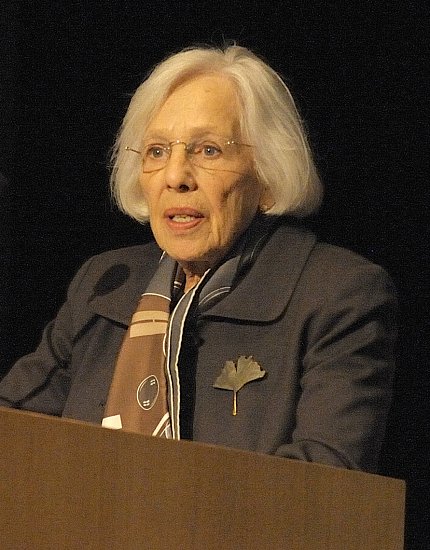

Dr. Maxine Singer, in Masur Auditorium during NIH Research Festival 2010 for a memorial tribute to Nobelist Dr. Marshall Nirenberg.

Early days of the molecular biologist in an NIH lab.

Singer, at a meeting called by NIH Director Dr. Donald Fredrickson on Feb. 19, 1977, to inform the scientific community and the media of legislation pending in Congress that was designed to regulate recombinant DNA research

“Science thrives under conditions where individuals of talent and skill have real independence,” Singer observed in a 1998 interview for an oral history of NCI.