Understanding Cognitive Load Theory Makes Teachers More Effective

Medical school curriculums require students to learn complex information. To help students retain what they’re taught, faculty and staff can use teaching principles based on cognitive load theory, said Dr. Jennifer Spicer, during a recent Graduate Medical Education Grand Rounds.

“We have a lot of evidence about how we learn,” said Spicer, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. “We know a lot about the science of how we learn and take in and retain information.”

Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental energy it takes to learn new information or perform a task. The theory proposes that people have a limited amount of energy available.

When a student is taught something new, that information goes into their working memory. Working memory can store only 5-7 pieces of information for 30 seconds. If a student focuses on a piece of information, it will move into long-term memory, where it’s believed there’s infinite storage.

“Working memory is the bottleneck for us being able to take in and understand information,” she said.

According to cognitive load theory, there are three components of working memory that affect how a student processes new information: intrinsic, extraneous and germane load. Intrinsic load refers to the information’s complexity; extraneous load refers to outside distractions and germane load refers to effort it takes to organize information.

In many cases, teachers don’t have much control over the difficulty of a course’s content. “There are just some topics that are really complex,” she said. “We have to think really carefully about how to manage the intrinsic load.”

There are strategies teachers can use to help students with difficult material. First, they must consider what a student is capable of learning. A first-year medical student, for example, doesn’t have the baseline knowledge that experts have.

Teachers can let students “preview” course material. This gives students a chance to familiarize themselves with unfamiliar terms so they can digest and understand them before class.

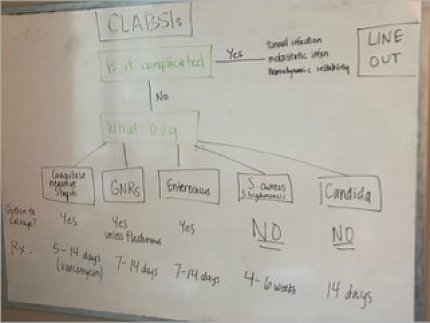

In the clinical setting, Spicer will give a 10-15 minute “chalk talk” before rounds. She structures these short talks around key concepts that students can build on later. Overwhelming students with too much too soon, she said, can interfere with their ability to learn.

She will also share relevant podcasts with her students in advance. To eliminate distractions, students turn their laptops and pagers off and put their phones away before class starts.

During multimedia presentations, Spicer limits the amount of text on slides so she can include complementary images, graphs and figures. She incorporates Mayer’s Multimedia Principles into her slide design. These principles state that people learn best when words are paired with images rather than words alone.

She prefers to give lessons using a conversational style, instead of scripting her lessons. “A conversational tone is much easier for people to take in and understand compared to a formal script.” Non-experts will also review her course materials to make sure she isn’t making assumptions about students’ knowledge.

Retrieving information from memory is an important skill for doctors when they make clinical decisions. During rounds, Spicer asks her students questions as a learning tool. “We’re forcing them to retrieve and apply information to patients in the future,” she said.

In the classroom, she gives students partial outlines of lectures. Data suggests that filling in partial outlines in their own words increases students’ long-term retention. Flash cards featuring questions that are harder than what’s on an exam also increases retention.

As students learn more, Spicer continues to challenge them. “We need to make things a little more difficult to really enhance learning.” She thinks about where she can stretch each student’s knowledge. For instance, a current student is learning how to deliver bad news to patients. She’ll prep her student about how to speak to a patient, role play a scenario and then bring her student into a patient room.

Before the visit, she tells the student: “I know this is going to be uncomfortable, but let’s try it. I’m here for support and you can turn to me if you get to the point where you can’t move forward.” These experiences are much more effective learning experiences, she said.

“Learning isolated facts doesn’t help unless we can apply them to situations,” she explained.

Finally, the best doctors are always working on something, even if they have long graduated medical school. Experts set goals for their learning and then practice and ask for regular feedback from colleagues. These high performers take the feedback and refine their approach over time.

Teachers must simplify and organize their content to help students learn, Spicer concluded. “We then want to engage in effortful, repeated practice on realistic and varied scenarios with targeted feedback.”