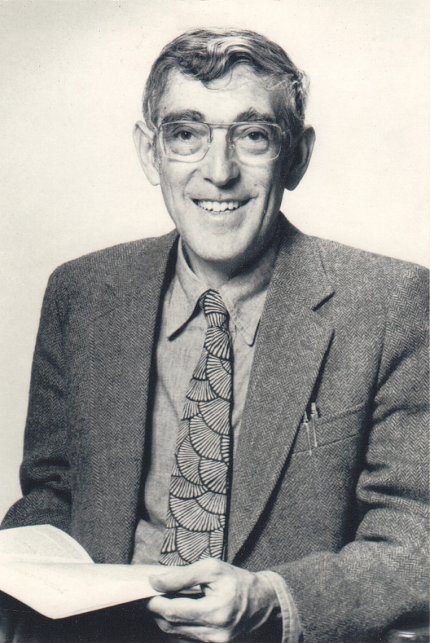

NIH Remembers Ames

Dr. Bruce Ames, creator of the simple and elegant Ames test to assess the potential carcinogenicity of chemical compounds in everyday products such as food and cosmetics, died on October 5, at the age of 95.

Ames worked at NIH from 1953 to 1967, first as a postdoc, then as a biochemist, and then as chief of the Microbial Genetics Section in the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in what is now the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). From his base in Bldg. 2, he created quite the stir among his NIH colleagues with his breakthrough biological assay employing strains of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium, which could develop mutations if “fed” certain chemicals.

The theory was if a chemical was mutagenic, it might also be carcinogenic, or cancer- causing because, as scientists (including Ames) were discovering at this time, cancer was linked to genetic mutations.

Fueled by their curiosity, Ames and his trainees fed the assay all types of substances, such as purified food additives, the urine of smokers and even wine. Ames left NIH in December 1967 for the University of California, Berkeley, where he further developed the test and published papers in the early 1970s on its potential for fast, inexpensive cancer assays that could be done in days, as opposed to carcinogenicity tests on rodents, which could take years.

The test was a sensation among trainees there as well. “They brought all kinds of things,” said Giovanna Ferro-Luzzi Ames, his wife, a scientist whom he met at NIH and is now professor emerita at UC Berkeley. “But memorably, one student brought his girlfriend’s hair dye. It was, as he said, ‘screamingly mutagenic.’”

The story goes that Ames sent his lab technician, a Japanese-American woman with raven-black hair, on a shopping spree to purchase every hair dye brand on the shelves, to the bemusement of the store cashiers. Many dyes tested positive for dangerous levels of mutagenic chemicals. Ames alerted the hair dye companies, which changed their formulas based on his testing.

Ames’ scientific contributions go well beyond the Ames test. During his time at NIH, peppered by a sabbatical year in 1961 as a senior fellow in the laboratories of Francis Crick in Cambridge and François Jacob in Paris, Ames specialized in the biochemistry of the histidine biosynthetic pathway in Salmonella bacteria. His work was foundational for understanding mutagenesis and mechanisms of gene regulation, and as such Ames was a major player in the rise of molecular biology, starting in bacteria but soon moving to eukaryotic cells.

Indeed, the Ames test was based on his observation that certain mutant strains of Salmonella unable to produce histidine, an essential amino acid, could acquire mutations that restored this ability, suggesting that carcinogenic agents stimulating such reverse mutations may do so at a rate proportional to their toxicity.

In the early 2000s, Ames turned his attention to the effects of nutrition on human health, which he developed into the concept called Triage Theory. He proposed that a shortage of an essential nutrient results in a redistribution of this nutrient to favor critical short-term metabolic functions at the expense of long-term health, and this tradeoff can lead to age-related diseases. Ames further proffered that vitamin D, rather than being a vitamin, should be seen as a hormone controlling thousands of genes.

Ames was honored with numerous accolades over the years. These include the 1998 National Medal of Science, more than 30 international honors and awards, and membership in the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is among the most cited scientists of all time.

The list of trainees that Ames had mentored is equally impressive and include Robert Martin, Gerald Fink, Harvey James Whitfield, John Roth, and Gisela Storz.

“Understand that Bruce never followed a straight and ‘logical’ course in his thinking,” said Martin, Ames’ first postdoc at NIH, who under Ames’ mentorship developed the process of sucrose gradient centrifugation. “If you fail to appreciate his flights of fancy, you would fail to appreciate the man and his imagination.”

While the Ames test revolutionized the field of toxicology, Ames did lament its overly zealous use. In a 2001 article in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Ames called himself a “contrarian in the hysteria over tiny traces of chemicals that may or may not cause cancer.”

“If you have thousands of hypothetical risks that you are supposed to pay attention to, that completely drives out the major risks you should be aware of,” he said. “I’m more interested in whether kids wear helmets when they ride their bikes, or if they eat enough fruits and vegetables.”

His wife, Giovanna, who hails from Italy, said she encouraged her husband to test all kinds of substances but once, jokingly, said “Don’t you dare test espresso.” Ames is survived by Giovanna, his daughter Sofia, his son Matteo, and his grandchildren, Dorotea and Giovanni.