End-of-Life Frankness

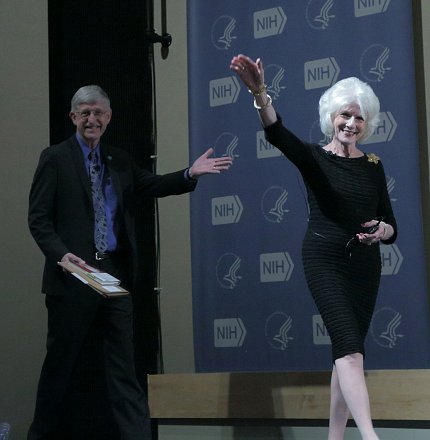

Rall Lecture Features Host-Guest Swap

Photo: Bill Branson

Maybe the key to being a longtime successful radio show host is being, oneself, quite interesting. That insight was gently excavated by NIH director Dr. Francis Collins over the course of an hour-long conversation with Diane Rehm at the Rall Cultural Lecture Apr. 7 in Masur Auditorium.

Part of the reason their public dialogue seemed so effortless is that Collins has been Rehm’s guest on NPR’s The Diane Rehm Show at least 10 times. Rehm said on-air interviews flow most smoothly when guests know their subject fully, and name-checked exemplars from NIH, including Collins, NIAID director Dr. Anthony Fauci and NIAMS director Dr. Stephen Katz.

Collins cheerfully acknowledged that turnabout is fair play at the outset of their conversation. “I step into the role she would normally play,” he said, admitting to feelings of pressure. It was now on him to make a guest feel at ease. He needn’t have fretted.

Collins first asked about Rehm’s non-traditional path to journalism. From there, the dominos fell.

Photo: Bill Branson

A native Washingtonian, Rehm graduated from high school in 1954. Neither of her parents thought college was for girls, so she became a secretary at the D.C. department of highways, deploying workers to fill the potholes her boss had noticed on his commute to work.

Recruited to another secretarial position at the U.S. Department of State, she found herself “surrounded by intellectuals,” including a particularly learned and handsome young man named John Rehm. “He became my teacher,” Rehm said, and eventually her husband.

She spent 14 years at home rearing two children before realizing, in 1973, that with kids growing up, she needed something to do.

Rehm enrolled in a class called “New Horizons for Women” at George Washington University, joining 19 other women who were segregated, by prior education, from the top of the building (graduate-level education) to the basement (where Rehm found herself, with other high school grads).

“They all said, ‘You really ought to be in broadcasting.’ I thought that was the craziest thing I’d ever heard,” said Rehm.

Within 2 weeks of finishing the course, Rehm talked with a friend who volunteered at a tiny radio station at American University. She encouraged Rehm to join her there.

The station was housed in a Quonset hut on campus. “If you went off the curb, you lost the signal,” Rehm joked. “This was when NPR was in absolute infancy.”

Offered a volunteer position, Rehm said, “A little light bulb went off in my head, and I accepted.”

On her first day on the job, the manager met her with bad news—the host was sick.

“I thought she was going to send me back home, but she said, ‘I want you to come in the studio with me.’ For 90 minutes, we interviewed a representative of the dairy council…Well, I knew about butter…”

Rehm’s husband was sure Diane had found a career, and predicted she would become the show’s host. “He had total faith in me.”

Rehm remained at the station as a volunteer for 10 more months, then spent 2 years as associate producer on the program, developing two health-related shows during that same period. She left that position to do some television and then was hired by the Associated Press as a freelance reporter specializing in medical research.

Rehm’s mother had died of liver cancer when Diane was 19, and her father died 11 months later, “literally of a broken heart. I wanted to know why.”

John Rehm’s father became diabetic, suffered from retinopathy and committed suicide; his wife, too, later killed herself.

“Death and illness and medicine have always been something I’ve had great interest in,” said Rehm.

She returned to WAMU as a full-time salaried employee in 1979, hosting the morning talk show Kaleidoscope, which was renamed The Diane Rehm Show in 1984.

Photo: Bill Branson

In the mid-1990s, Rehm began experiencing problems with her voice. “I felt my voice clutching and clamping. It started with a tiny little cough.”

It became repetitive, and guests, including Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), noticed it. Rehm recalls, “I couldn’t do the show [with Mikulski]. I had tears in my eyes. And she said, ‘If you need help, I’ll get you to NIH.’”

By February 1998, Rehm’s voice had become a choked stutter and she left the air. For 4 months, she sat at home “not answering the phone, not speaking to anyone except my husband, not leaving the house.”

A neurologist and an otolaryngologist at Johns Hopkins diagnosed her with spasmodic dysphonia, a vocal cord problem amenable to treatment with the then-new therapy of Botox injections. Ironically, the same neurologist who made this discovery also diagnosed her husband’s Parkinson’s disease.

While waiting for her voice to return after the Botox injection, Rehm was invited by Slate to keep a diary of her recovery, which proved to be therapeutic.

That skill served her most acutely as she came to grips with her husband’s advancing illness.

“At the end, John Rehm could no longer use his hands, no longer feed himself, stand, walk to the bathroom or care for himself in any way.” The family gathered to hear his decision: “I am ready to die.”

John asked his doctor to help him die, but the doctor said he could do nothing, noting that it was against Maryland law. “Only you can make this happen,” said the doctor, advising him to suspend food, water and medication.

“We all left, not knowing what John’s decision was going to be,” Rehm recalled. The next day, Rehm took him a photo album she had long ago created of his early years in Paris, where he was born, through his prep school years in New York.

“He looked so well that day. He said he had not eaten or had anything to drink or taken any medication, ‘And I feel great!’

“I know why he felt great—he felt like he had taken his life back into his own hands.”

Rehm and her husband, who was 6 years older, had spoken a great deal about end-of-life issues and had promised that they would help each other die when the time came.

Assured that he was doing what he wanted, Rehm stood by his side as he proceeded on his end-of-life journey.

“For the next 2 days, his face was pink and he looked wonderful,” Rehm said. “At the end of the second day, he fell asleep and never woke again.”

Photo: Bill Branson

Rehm addressed the audience: “I ask all of you—have you talked with your family about what you want?”

Rehm, who has written a book—On My Own—about losing her husband, says she’s not an advocate of anything other than having the discussion about the end of life, regardless of faith or other considerations.

“In St. Louis, there’s now a group called Coffee & Death,” she said. “These are friends and neighbors who gather to talk about exactly what they want [at the end of life]. Everyone in the neighborhood knows, not just family and friends.

“This country has been death-averse,” she charged, urging Collins and the medical profession to find ways to surrender the heal-at-all-costs mindset. “We need to talk more openly,” Rehm said, noting that several states have already adopted right-to-die statutes.

For his own part, Collins said he was grieving Rehm’s decision to retire The Diane Rehm Show after the 2016 elections. He asked her why.

“Because I turned 79 last September,” she said. “It struck me that 80 was a good time…I’ve had that real estate for 37 years, 2 hours a day. Dr. Collins, don’t you think that’s enough?”

After she leaves the microphone, Rehm plans to “talk a great deal about the right to die, also about Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease.”

The audience gave her a standing ovation as she left the stage. The entire conversation is archived at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=18852&bhcp=1.