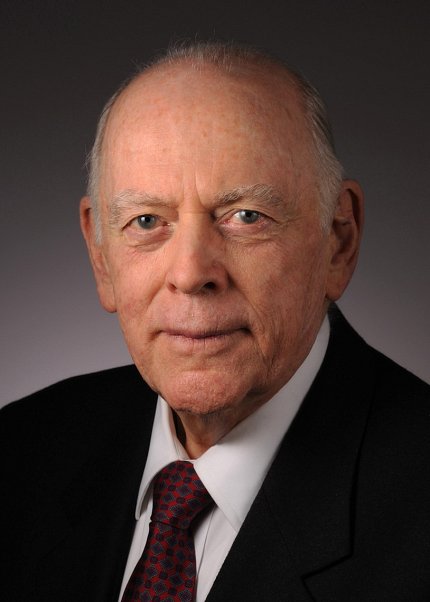

NINDS Mourns Scientist Emeritus Brady

Dr. Roscoe Owen Brady, scientist emeritus and retired chief of the Developmental and Metabolic Neurology Branch, NINDS, died on June 13 after a long battle with cancer. He was 92 years old.

Brady was a pioneer of modern medicine. For more than 50 years, he conducted research on hereditary metabolic storage diseases, also called lipid or lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) such as Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Fabry disease and Tay-Sachs disease. His work defined much of what is known about the biochemistry, enzymatic bases and metabolic defects of these disorders. He inspired colleagues throughout the world to define the causes of many other related disorders and to pursue further investigations in the field of metabolic neurology.

Born in Ambler, Pa., in 1923, Brady attended Pennsylvania State University and earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1947.

After graduating, he interned at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and later became a National Research Council fellow and a Public Health Service special fellow in the department of biochemistry at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He worked with Dr. Samuel Gurin, a biochemist, on research using radioactive isotopes to study the biosynthesis of testosterone, fatty acids and cholesterol.

One of Brady’s early scientific contributions was discovering the role of gonadotrophin on testosterone synthesis. This work not only spurred his desire to do research, but would eventually lead to his interest in lipid storage diseases.

In 1952, Brady was called to active duty in the Korean War and, for 2 years, served in the U.S. Naval Medical Corps at the National Naval Medical School in Bethesda as officer-in-charge of the department of chemistry.

Brady was recruited by Dr. Seymour Kety in 1954 to join NINDB (now NINDS) as chief of the section on lipid chemistry in the Laboratory of Neurochemistry. Kety wanted to establish a research program focused on myelin—the lipid coverings of nerves-—and he knew of Brady’s research at Penn. Brady would remain with NINDS for his entire career, later becoming chief of the Developmental and Metabolic Neurology Branch and eventually retiring in 2006.

While there is a great deal of research on LSDs today, there was virtually none before Brady’s investigations at NIH.

In addition to identifying the enzymatic bases, he and his research team developed diagnostic tests, carrier identification procedures and methods for prenatal detection of these disorders that provided the basis for genetic counseling to at-risk families. In 1991, they established the first effective treatment—enzyme replacement therapy—for Gaucher disease.

“As soon as we identified the missing enzyme in Gaucher disease and Niemann-Pick disease, I thought about enzyme replacement therapy,” said Brady in a 2008 interview. “Although it took many years to bring enzyme therapy to fruition, the ultimate benefit was amazing. It showed the way enzyme replacement therapy can work for human diseases.”

His studies on Gaucher disease and success with enzyme replacement therapy led to breakthroughs in other areas of LSD research, including a treatment for Fabry disease and the identification of new types of LSDs.

By taking their discoveries from bench to bedside, Brady and his team brought enormous relief to patients, who without treatment suffer from a wide range of symptoms including liver and spleen enlargement, severe anemia, thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count) and painful skeletal deformities.

“Dr. Brady’s work with enzyme replacement therapy launched an important part of the biotech and pharmaceutical industry and it brought effective treatment to patients who had none,” said Dr. Kenneth Fischbeck, chief of NINDS’s Neurogenetics Branch. “I remember meeting with him when I first came to the NIH and he showed me pictures above his desk of patients who would not have been alive if not for the treatment he helped to develop. That’s a worthy goal for all of us who are still working to fulfill the promise of safe and effective therapy for patients with hereditary diseases.”

In 2002, NINDS held a 2-day symposium to honor Brady’s research career. The meeting, which gathered top scientists to discuss past accomplishments and future directions of hereditary metabolic disorders research, celebrated the remarkable progress that has been made in understanding and devising therapies for these disorders and recognized Brady for his leadership.

At the time he retired, he had served as chief of the branch for 34 years. His work, however, continued as he transitioned to an emeritus role in the institute. Even after retirement, he kept searching for other ways to treat LSDs, including looking at molecular chaperone therapy—which provides a template to guide and stabilize the abnormal enzyme—and at gene therapy as a possible cure. He maintained an office adjacent to the NINDS Surgical Neurology Branch.

“Dr. Brady biked or drove his convertible to NIH at least 3 days per week,” said SNB chair Dr. John Heiss. “He worked all day, keeping up with developments in the field of LSDs and becoming an expert in the biochemistry of tumorigenesis. His office door remained open and through it passed all levels of scientists, from principal investigators to IRTAs. They left his office with scientific insights, manuscript editing and valuable mentorship. His keen intellect defied the aging process.”

Throughout his career Brady received numerous accolades: the Lasker Foundation Award (1982), the Kovalenko Medal from the National Academy of Sciences (1991) and the Alpert Foundation Prize from Harvard Medical School (1992).

In 2008, he received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, the highest honor for achievement in science and technology bestowed by the President of the United States. He had been nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology by other Nobel laureates.

Brady published hundreds of research articles and authored or co-authored nearly 50 scientific manuscripts after “retiring.” He trained many doctors and, until recently, regularly attended and contributed to NINDS grand rounds and scientific conferences. He served on editorial and advisory boards for many journals and organizations and was an adjunct professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Brady was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine. His work is featured on the NIH Office of History web site, www.history.nih.gov/exhibits/gaucher/index.html.

Brady is survived by his wife Bennett, sons Roscoe Jr. and Owen, and granddaughters Elinor and Beatrice.