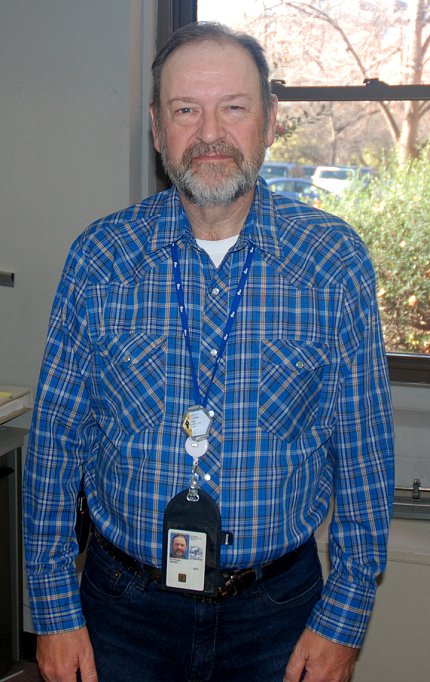

Putnam Retires After 42 Years at NIH

The Cal Ripken Jr. of radiation safety has hung up his cleats.

On Jan. 2, Israel Putnam retired as radioactive material supply management officer in ORS’s Division of Radiation Safety, Materials Control and Analysis Branch. His wife nicknamed him the Ripken of radiation safety because both men spent their entire careers in one place.

Putnam was in charge of the radioactive material inventory used in biomedical research at NIH. Radioactive materials are used for cancer treatments, biological research and in medical imaging. Most of the radioactive material at NIH is not dangerous if handled properly, he noted.

He kept track of all radioactive materials coming in and out of NIH and how they were used. He also helped ensure that NIH was in compliance with Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulations.

“Israel has been a stalwart employee of DRS and long ago established himself as the subject matter expert on radioactive materials shipping/receiving,” said Cathy Ribaudo, director of the Division of Radiation Safety. “Over the past 40 years, he has likely spoken with every single principal investigator who has ordered radioactive material for his or her lab and every purchasing agent who has procured it. He’s had an amazing career and I’m deeply appreciative of his many years of service to NIH.”

After he graduated from Paint Branch High School in Burtonsville, Md., Putnam began working at NIH as a radioactive waste physical science aid. He worked part-time and took college courses at night. Two years later, he became a full-time employee.

“I got married young, so I had kids young. I had to work,” he said.

When he first started, his division handled 35,000 shipments of radioactive material a year. They don’t process that many anymore, but Putnam was just as busy as ever. The NRC requires more information about NIH’s nuclear materials than before. He didn’t enjoy enforcing the rules, but knew that he had to in order to advance NIH’s mission.

When a shipment of radioactive material for patients arrived, Putnam and his staff delivered it as fast as possible. Some drugs, for example, have a half-life of 3 hours, which means they become ineffective quickly. Putnam ensured that the packages arrived on time—even if he had to deliver them personally.

Last winter, a snowstorm dumped 2 feet of snow on campus. Although federal offices were closed for 2 days, the Clinical Center stayed open. Researchers still needed their shipments. Putnam dug himself out of his neighborhood in Burtonsville, drove to Bethesda and delivered the goods.

“If I need to be here, I’m going to be here,” he said.

Once, he came into work to solve a problem on the same day his daughter was born. When his daughter was getting married, he oversaw the shipment of a 35-ton cyclotron from NIH to a laboratory in Idaho.

In retirement, he plans on fixing up his townhouse in Burtonsville. A year and a half ago, his wife passed away, so he’ll spend time with his children, Andrea and Michael, and his two grandchildren. In 2017, he’ll spend January in Las Vegas and March in Daytona Beach. And in August, he’ll be in Wyoming to watch the total solar eclipse.

“I get to miss most of winter this year,” he exclaimed.