NIH Researchers Uncover Drain Pipes in Our Brains

By scanning the brains of healthy volunteers, researchers at NIH saw the first, long-sought evidence that our brains may drain some waste out through lymphatic vessels, the body’s sewer system. The results further suggest the vessels could act as a pipeline between the brain and the immune system.

“We literally watched people’s brains drain fluid into these vessels,” said Dr. Daniel Reich, senior investigator at NINDS and senior author of the study published online in eLife. “We hope that our results provide new insights to a variety of neurological disorders.”

Reich is a radiologist and neurologist who primarily uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders thought to involve the immune system. Led by postdoctoral fellows Dr. Martina Absinta and Dr. Seung-Kwon Ha, along with researchers from NCI, the team discovered lymphatic vessels in the dura, the leathery outer coating of the brain.

Lymphatic vessels are part of the body’s circulatory system. In most of the body they run alongside blood vessels. They transport lymph, a colorless fluid containing immune cells and waste, to the lymph nodes. Blood vessels deliver white blood cells to an organ and the lymphatic system removes the cells and recirculates them through the body. The process helps the immune system detect whether an organ is under attack from bacteria or viruses or has been injured.

In 1816, an Italian anatomist reported finding lymphatic vessels on the surface of the brain, but for two centuries, it was forgotten. Until recently, researchers in the modern era found no evidence of a lymphatic system in the brain, leaving some puzzled about how the brain drains waste and others to conclude that the brain is an exceptional organ. Then in 2015, two studies of mice found evidence of the brain’s lymphatic system in the dura. Coincidentally, that year, Reich saw a presentation by Dr. Jonathan Kipnis, a professor at the University of Virginia and an author of one of the mouse studies.

“I was completely surprised,” said Reich. “In medical school, we were taught that the brain has no lymphatic system. After Dr. Kipnis’s talk, I thought, maybe we could find it in human brains?”

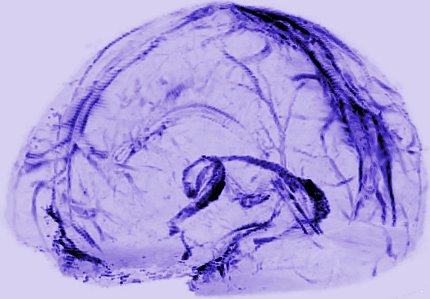

To look for the vessels, Reich’s team used MRI to scan the brains of five healthy volunteers who had been injected with gadobutrol, a magnetic dye typically used to visualize brain blood vessels damaged by diseases such as multiple sclerosis or cancer. The dye molecules are small enough to leak out of blood vessels in the dura but too big to pass through the blood-brain barrier and enter other parts of the brain.

At first, when the researchers set the MRI to see blood vessels, the dura lit up brightly and they could not see any signs of the lymphatic system. But, when they tuned the scanner differently, the blood vessels disappeared and the researchers saw that dura also contained smaller but almost equally bright spots and lines that they suspected were lymph vessels. The results suggested that the dye leaked out of the blood vessels, flowed through the dura and into neighboring lymphatic vessels.

“These results could fundamentally change the way we think about how the brain and immune system inter-relate,” said NINDS director Dr. Walter Koroshetz.