Soul Man

Moreland Speaks at First ‘Science & Philosophy’ Event

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Perhaps neuroscientists should focus solely on the brain and leave matters of the mind to philosophers. It’s a popular view held by many academic philosophers as well as neuroscientists. After all, both heady disciplines are equally fascinating and multi-faceted, and some investigators of each may only agree that one may never fully understand or explain the other.

On the other hand, both fields are subject to investigation, testing and the laws of logic. Research in neuroscience can’t avoid ultimate implications in the realm of philosophy.

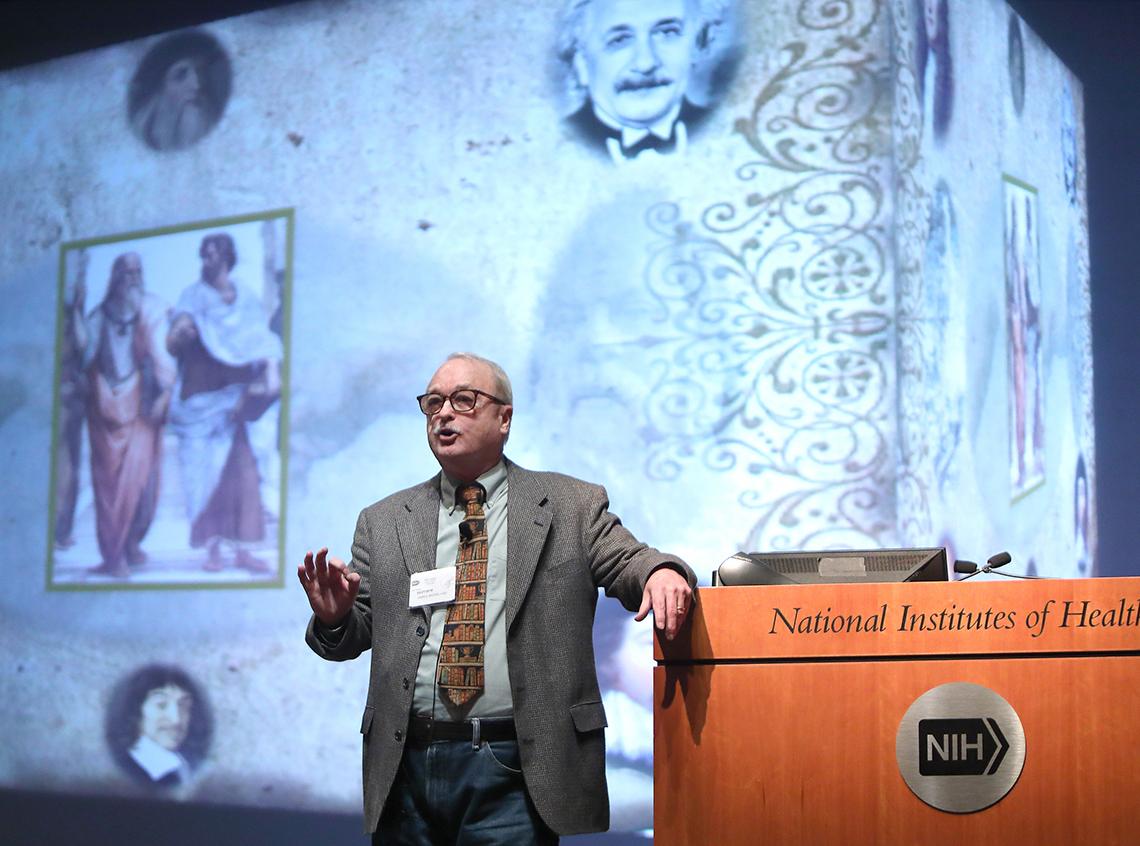

Philosopher Dr. J.P. Moreland explored such dueling perspectives recently in his talk “Philosophical and Empirical-Neuroscience for Determining the Nature and Existence of Consciousness and the Soul,” the first lecture in a series hosted by the newly formed NIH scientia et philosophia interest group.

The philosopher began by citing a few prominent neuroscientists, including DNA structure co-discoverer Dr. Francis Crick and his colleague Dr. Christof Koch, who co-wrote articles two decades ago on studying consciousness. Moreland said Crick and Koch acknowledged in a 1998 Cerebral Cortex article “that the main attitude among neuroscientists is that the nature of consciousness is ‘a philosophical problem and best left to philosophers.’ Elsewhere they claim that scientists should concentrate on questions that can be experimentally resolved and leave metaphysical reflections to philosophers.”

Koch, it should be noted, is world- renowned for his research on the neural bases of consciousness and his articles touting the latest neurobiological tools scientists are using to study it.

Listed by The Best Schools web site as “one of the world’s 50 most influential living academic philosophers,” Moreland is distinguished professor of philosophy at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University in La Mirada, Calif. He’s had considerable time and occasion to contemplate diverse perspectives on consciousness and his conclusion remains constant.

“I think neuroscientific contributions are best when dealing with correlations, causal relations or functional dependencies and discovering more and more details on those,” he said. “I think it is philosophical reflection that gets at the very fundamental heart of what exactly is consciousness and what it is that owns or possesses consciousness.”

Lest anyone be confused, Moreland defined the brain and brain events and the mind and conscious events as distinctly different. Just because something your brain does—call it a “brain event”—leads your mind to produce something—call it a “mental event”—does not necessarily mean that the two events are the same thing, he explained.

One—the brain—has definable and measurable physical properties that can be shown by electroencephalogram and positron emission tomography scan, for instance. Measurements of the mind’s properties, however, are far more elusive and difficult to document “from a third-person perspective, but have a distinct, qualitative texture or a ‘what-it-is-like’ to them that is made clear to focused, first-person introspection,” Moreland said.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Scientists and philosophers have been having mind-body discussions for many years, with all sides endeavoring to clarify and inform their own work as well as its relationship to the others. As a matter of fact, experts from several viewpoints have gathered for hours to debate the topic right here at NIH on at least a couple of occasions within the past 20-odd years.

On Feb. 27 in Masur Auditorium, however, Moreland flew solo and had just 60 minutes that he managed to stretch into 90 and beyond at a post-lecture reception in the FAES bookstore after the formal talk.

In what had all the elements of an advanced grad school course in philosophy—complete with syllabus and bibliography hand-outs upon entry—the professor talked about ontological questions and “the inadequacy of empirical neuroscientific methodology” to answer them.

Moreland discussed the Law of Identity (also known as Leibniz’s Law of the Indiscernibility of Identicals) and why you can’t just say the mind is the brain and the brain is the mind.

“Identity is not cause and effect, it’s not correlation and it’s not functional dependency,” Moreland explained. “Just because a mental state functionally depends for its obtaining on a brain state, that is not sufficient to show that the mental state is identical to the brain state.”

He went over such basic concepts as “mere property dualism,” “physicalism” and “substance dualism” and their differences. To illustrate, he explained how each theory would explain why someone might not be able to experience empathy.

The physicalist, for example, would say the person must have a misfiring neuron somewhere in his brain because otherwise a normal-firing neuron is identical to the feeling of empathy; locate/fix the mechanical problem and his ability to feel empathy should be restored. Not so fast, say the other camps.

Moreland said the two dualists would agree with each other, but for different reasons.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

The mere property fan would argue that although empathy is a mind event—“a state of consciousness that can’t be reduced to anything physical”—it happens in the brain and relies on a properly functioning brain in order to occur. “Just like if your eyes get put out, then you can’t have visual sensation, the sense of sight.”

The substance dualist, Moreland noted, would say, “I don’t think the brain is the kind of thing that can have consciousness. The proper nature of the owner of consciousness would have to be a part-less unextended spiritual entity of some kind, but while embodied, there will be an ontological cause-and-effect relationship that goes both ways. If your neurons [in the brain] don’t work then you will not be able to have feelings of empathy in the ego or the self. Occurrences of those feelings still rely on a properly functioning brain, but they are owned by a soul or self. ”

Moreland also described the nature of phenomenal consciousness and its five states: sensations, thoughts, beliefs, desires and volitional exercises of active power.

Phenomenal consciousness, he explained, is what people experience as they’re coming to in the recovery room after surgery. Slowly they’re gaining an awareness that only they can experience.

“For any physical object, property or state, we all have equal access to that—including brain measurements—because they’re publicly accessible objects,” he explained. “Consciousness, however, has a way of being known that is not true of any physical state…The person who’s having the state is directly, uniquely aware by way of introspective, private access to the state of consciousness.”

Moreland closed with several arguments for the soul being distinct from the physical body. A person is separate from the gray matter that makes up his or her brain. For one thing, the brain can be divided and even have parts removed, but the individual—the person, the soul—remains the same throughout the diminished capacity of cognitive abilities or loss of brain function.

“The soul is an immaterial substance or thing that contains consciousness and enlivens or animates the body,” Moreland said. “If you don’t like the word ‘soul’ just substitute the word ‘self’ or ‘I’ or ‘ego’ or ‘mind.’”

For details about the new interest group and its upcoming meetings and events, visit https://oir.nih.gov/sigs/scientia-et-philosophia-interest-group.