NIH Grantees Win Nobel Prizes

Three NIH grantees won 2018 Nobel Prizes, one in physiology or medicine and two in chemistry.

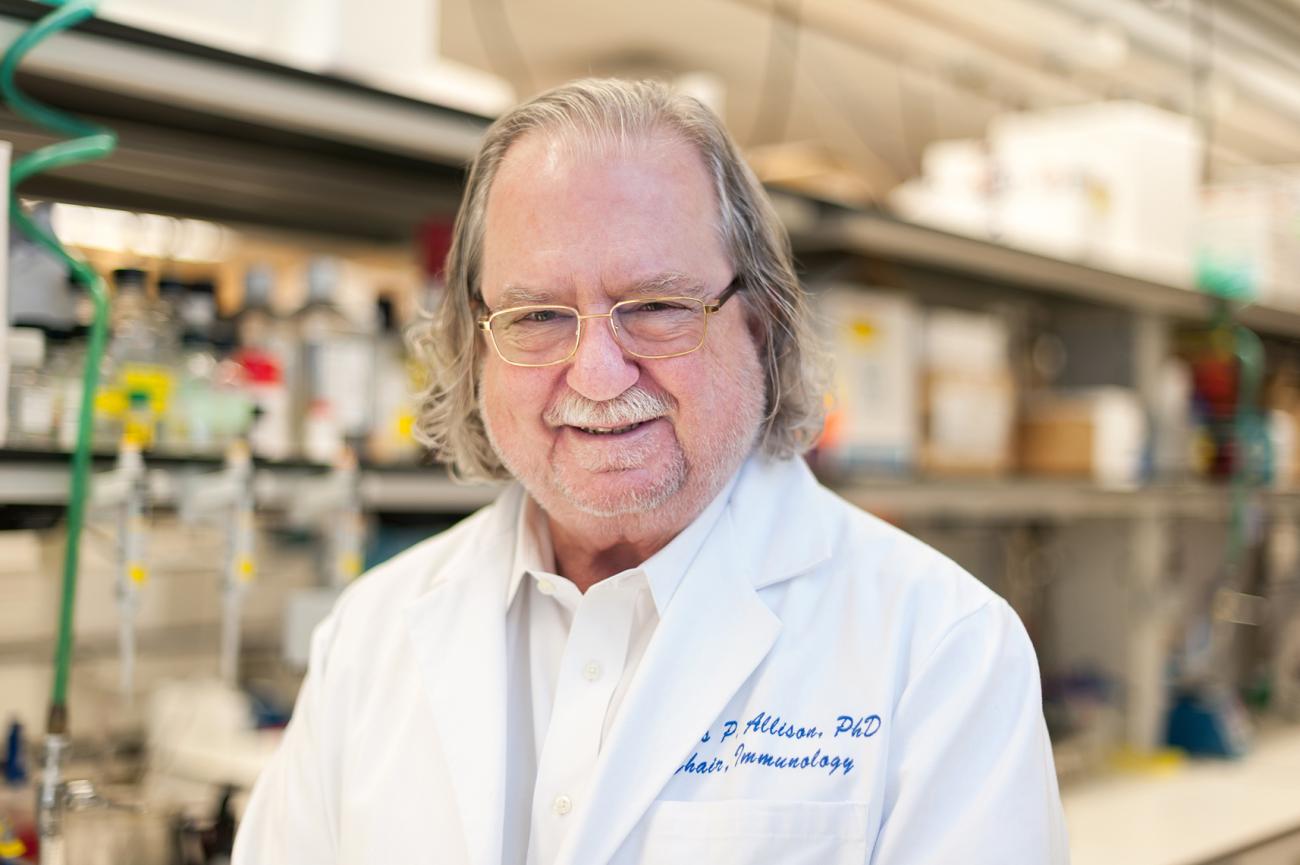

In medicine, Dr. James P. Allison of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center shared the prize with Dr. Tasuku Honjo of Kyoto University Institute, Japan, for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said, “By stimulating the inherent ability of our immune system to attack tumor cells, this year’s Nobel laureates have established an entirely new principle for cancer therapy.”

Allison discovered that a particular protein (CTLA-4) acts as a braking system, preventing full activation of the immune system when a cancer is emerging. By delivering an antibody that blocks that protein, Allison showed the brakes could be released. The discovery has led to important developments in cancer drugs called checkpoint inhibitors and dramatic responses to previously untreatable cancers. Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells and revealed that it also operates as a brake, but with a different mechanism of action.

Allison has received continuous funding from NIH since 1979, receiving more than $13.7 million primarily from the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Honjo was a postdoctoral fellow at NIH for a year early in his career, and also was a visiting fellow intermittently thereafter.

The chemistry award went to grantee Dr. Frances H. Arnold of the California Institute of Technology, for directed evolution of enzymes, and to grantee Dr. George P. Smith of the University of Missouri-Columbia, who shares the prize with Dr. Gregory P. Winter of the University of Cambridge, U.K., for the phage display of peptides and antibodies.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said, “This year’s chemistry laureates have taken control of evolution and used the same principles—genetic change and selection—to develop proteins that solve humankind’s chemical problems.”

Arnold conducted the first studies on the directed evolution of enzymes, which are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. These studies have demonstrated how rapidly some proteins can evolve under selection pressure to develop new properties such as faster catalysis or the ability to act on non-natural molecules. Enzymes produced through directed evolution are used to manufacture everything from biofuels to pharmaceuticals.

Smith developed a method known as phage display, where a virus that infects bacteria called a bacteriophage can be used to evolve proteins with new functions. Winter has used phage display to produce new drugs. Today, phage display is a fundamental technology used for drug discovery and has resulted in several important medications.

Both Arnold and Smith each have received more than $2.5 million, primarily from the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences. Smith’s early work was also funded by NIAID.

How Shiny Is a Nobel Prize Medal?

You don’t need sunglasses, but seeing a Nobel Prize in person is an awe-inspiring experience.

It’s bright. It’s beautiful. It’s impressive.

Anyone curious about what exactly a Nobel Prize looks like is welcome to visit the Reading Room of the National Library of Medicine’s History of Medicine Division, where the Nobel Prize awarded to Dr. Marshall Nirenberg is on permanent display.

The medal can be viewed upon request during library hours, Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m.–5 p.m.