‘Tulipmania’

Exhibit in CRC Reveals Flower Genome, Art of Science

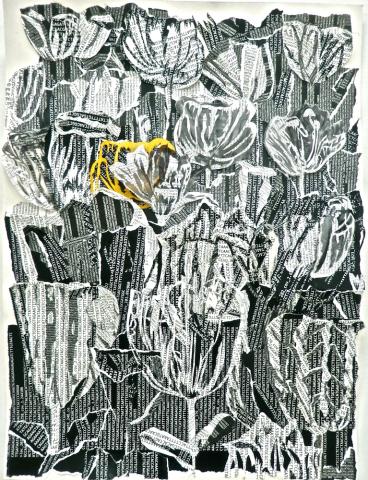

The more no’s she heard, the more motivated artist Anna Fine Foer became. Her latest exhibit, which combines art, genomics, history and horticulture, was born essentially of dismissal. Nearly 2 years in the making, “Tulipmania and the Tulip Genome” is now on display in the Clinical Research Center.

“I’ve been inspired by scientific concepts for awhile after watching episodes of NOVA, the [Public Broadcasting Service] show on TV or listening to [WNYC’s] Radiolab or reading articles in the press,” Foer said.

When she learned she’d won the opportunity to show work at NIH, she shared the news with long-time friend and NIH’er Dr. Henry Levin, senior investigator and head of the section on eukaryotic transposable elements in NICHD’s cell regulation and development group.

“I knew immediately that I wanted to collaborate with him,” she said.

Levin’s lab studies “the biological impact of transposable elements using high-throughput DNA sequencing,” he explained. “Recent projects include the finding that transposable elements in fission yeast are the major drivers of adaptation when cells are exposed to stress. We also study the role of transposable elements in human disease, including mental illness.

“I’ve known Anna for over 20 years and have been intrigued by her artistic interests,” Levin continued. “In particular, I have been fascinated by her collages portraying social and scientific concepts. When the draft sequence of the human genome was first published, I thought she might be inspired by the images in the special issue of Nature that described the breakthrough. I think that sparked her interest in DNA and the coding potential it had to portray all of biology.”

Indeed, Foer was enthused by genomics, taking in all she could learn about the topic through books and lectures. At about the same time, she also was reading up on the 16th century Dutch tulip craze that had brought the flower into worldwide prominence. Foer determined to combine the two pursuits in her art.

“Over the years we have talked about her projects, including her passion for tulips,” Levin recalls. “When Anna showed me the images of broken tulips, I immediately thought their sectored petals were the result of transposable elements. I’ve come to recognize the typical sharp lines of color variation they produce in plants when, during tissue growth, they damage pigment genes. The sharp lines of color in maize kernels were the clue that led [Nobel laureate] Barbara McClintock to discover transposable elements. In reading more about broken tulips, I discovered that mosaic virus, not transposable elements, was responsible for the stunning patterns of these highly prized plants.”

“I decided to find the genome of tulips and use the code as the material for my collages,” Foer explained. That’s when she began meeting resistance. The tulip genome would be too big and too expensive to sequence, she was told repeatedly by scientists and experts of most every stripe. Foer kept searching for ways it could be done, however.

After a lecture on CRISPR/Cas gene editing, held in late 2017 at the National Academy of Sciences in D.C., Foer raised a question about genome sequencing to the speaker, whose response was, basically, “It’s a science thing—you wouldn’t understand it if you saw it.” Foer replied, “I have to see it to understand it.”

Foer was hurt and discouraged, but not deterred. “I really couldn’t believe it,” she said. “Artists can use a concept in their work without understanding it the way that scientists do.”

Then, serendipity stepped in.

“I was introduced to Nicholas Schurch, a computational biologist, at a SciArt conference in December [2017] in New York City,” Foer recounted. “It was a result of my comments about being dismissed by the geneticist working with CRISPR at the NAS—that was the instigation.”

Schurch knew of someone who had sequenced the tulip—in Leiden, South Holland, no less, the proverbial home of the flower. Did the artist want to be put in touch?

Foer immediately contacted the sequencer, Dr. Christiaan Henkel, who was happy to share his group’s raw data, which amounted to 45 pages of black type on 8.5 x 11 paper. Someone familiar with genetic code told Foer she probably had not received the flower’s entire genome—just a relevant fraction.

“When I first saw the tulip code, I was excited because it looked like it could be tulips, turned on its side,” said Foer. For the next year, she developed a collection of 12 collages illustrating the tulip genome, which eventually would be framed, mounted and shown for the first time at NIH—home to scientists responsible in part for publishing the human genome sequence in the Feb. 15, 2001 issue of Nature that Levin gave Foer.

Her exhibit incorporates materials such as hand-dyed rice paper, watercolor and vellum as well as mirrored and metallic papers to give viewers a sense not only of the beauty and science of tulips, but also of the history of their popularity and importance economically to Holland specifically and Europe in general.

Beyond a typical viewer’s appreciation of aesthetic, Levin sees Foer’s work—and fine art in general—providing much more to researchers on any number of levels.

“My interest in Anna’s work comes from her keen ability to see patterns when others don’t,” Levin said. “I have always wanted her help in developing imaging software that would portray the complex patterns of repeats [that] transposable elements make across chromosomes. This is just one example of how the talents of a gifted artist can help scientists decipher the mysteries of natural patterns.”

“Once this information is made available, there’s no telling how it will be used,” Foer agreed, explaining her own aspirations for the work beyond the 8-week NIH show. She’s also uploaded the collection to her website.

The last piece—“Boeket Tulpen,” Dutch for bouquet of tulips—is a culmination of what the artist learned throughout the nearly 2 years it took to research and produce the exhibit. “It’s the only one that I knew what it was going to be when I started,” Foer said. “The tulip genome is part of the landscape. The vase was inspired by a 17th century cabinet of curiosity. [Boeket Tulpen] puts the genome in historic context.

“I really want to emphasize three aspects that make this significant—especially now,” she concluded. “First, it’s the intersection of art and science. Also, it’s using and viewing the genome in an unintended way. And finally, the international aspects of scientific research—it’s the perfect example of why we need to keep people from all over the world coming here to the United States.”

Without cross-pollination of many different cultures from many different countries, the science of tulips, and Tulipmania, could not occur, she said.

The historic nature of her work is not lost on Foer either. “A hundred years from now people are going to look at the first images of the tulip genome,” she noted, “and I’m going to be a part of it.”

Financially supported in part by the Randall Frank Contemporary Artist Grant Program and the Giving Spirit Foundation Unicorn Barn Project, Tulipmania will be on display in the CRC main entry through Mar. 1.

See Foer’s work online at www.annafineart.com/art/.