Sixth Intramural Laureate

NIH’s Alter Wins Nobel Prize

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

When the phone rang at 4:15 a.m. on Oct. 5 at Dr. Harvey Alter’s house, he ignored it.

“It got me out of a deep sleep, and woke my wife, too, but we decided not to answer it,” he said.

Five minutes later, it rang again, and the Alters once again blew it off.

“It rang a third time, and I got out of bed rather angrily, figuring it was either a political solicitation or an offer to extend the warranty on my car,” he said. “But it was a man from Stockholm. It left me dead in my tracks.”

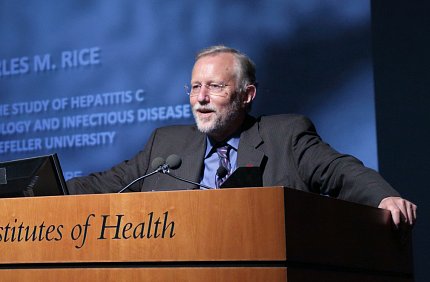

Alter learned he had won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions to the discovery of the hepatitis C virus. He shares the award with longtime NIH grantee Dr. Charles M. Rice of Rockefeller University and Dr. Michael Houghton of the University of Alberta.

“I’m really humbled by this whole event,” said Alter at a 10 a.m. conference call with reporters, during which he reviewed a half-century of work that he called “a tribute to non-directed research…You don’t know where you’re going, but you just keep going.”

“This is a source of great joy and pride,” said NIH director Dr. Francis Collins, who opened the telebriefing. “In a career of more than 50 years at the Clinical Center, Dr. Alter has done work that is not just beneficial, but now curative…He is the perfect person for this honor—persistent, dedicated, creative. He cares deeply about saving lives. We are just thrilled.”

“This is a great day for the NIH Clinical Center,” said hospital CEO Dr. James Gilman, “and a great day for science…[Alter] is somebody that everybody at the Clinical Center has not only respect, but also affection, for. He’s one of the really good guys, with a sense of humor, approachability and accessibility. I couldn’t be prouder of the Clinical Center or the department of transfusion medicine. We are very grateful for having had the chance to get to know him.”

“What a treat!” enthused Dr. John Gallin, who directed the CC for much of Alter’s career and is now NIH associate director for clinical research. “He is the consummate clinical investigator, a wonderful physician who cares passionately about his patients...I believe that his work could not have been done easily anywhere else in the world.”

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Alter had planned on a career in clinical medicine when he arrived at the NIH blood bank in 1969. But while working with Nobel laureate Dr. Baruch Blumberg, he found an interesting antigen. “It was the surface coating of the hepatitis B virus,” he said, and it proved to be the basis for a test to keep donated blood safe.

The excitement of the discovery changed his career path. He and his blood bank colleagues began following patients after they had undergone open-heart surgery at NIH, because about a third of such patients later developed liver abnormalities resembling hepatitis. The scientists were keen to discover the cause.

For 6 months, they checked on these patients weekly and stored their blood samples.

“We were astounded to find that 30 percent later got hepatitis,” said Alter.

Further investigation revealed that, if the patients had received blood from paid donors, they had a 51 percent chance of acquiring hepatitis, versus only a 7 percent chance if the donors were volunteers. So in 1970, the NIH blood bank adopted a policy of all-volunteer donations if patients were to be later transfused. That year, the first test for hepatitis B debuted, causing “a precipitous drop [in post-surgical cases of hepatitis], to 10 percent,” said Alter.

But it didn’t go to zero. What else was going on?

“In the ensuing years, we didn’t know where we were going,” he said, but the scientists kept up their search for all causes of post-transfusion hepatitis. In the mid-1970s at NIH, researchers discovered the hepatitis A virus. That enabled Alter and his team to take advantage of the “enormous value of stored samples” to tease out hepatitis cases unrelated to either the A or B forms—and there were a lot of those. They dubbed the culprit “non-A, non-B hepatitis.”

“Fifteen years later, we still didn’t know what the agent was,” he related. But they knew something about it. Animal studies and filtration experiments suggested the agent was a small virus, likely an RNA virus.

“We were still stuck through the 1980s, without having really identified the agent,” said Alter. “But then, the field of molecular biology began to emerge…We were upstaged by [co-laureate] Houghton, working at Chiron, when they cloned the non-A, non-B agent,” later known as hepatitis C.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

The Chiron team developed an antibody assay that Alter put to the test by pitting it against a coded panel of stored blood samples. It found every single case. The test later became even more sensitive, so that by 1997, rates of post-transfusion hepatitis dropped virtually to zero, with no cases since, Alter said.

Co-laureate Rice provided the ultimate proof that this virus was responsible for hepatitis C by recreating its genome in the lab and showing that it could transmit the disease to animals. Years later, investigators at Gilead developed a game-changing drug whose effectiveness is now at almost 100 percent, said Alter. “We can cure almost all carriers. It may be possible even to eradicate this disease in the next decade, even in the absence of a vaccine. A vaccine is still the goal, though.”

During a Q&A session with reporters, Alter, 85, acknowledged, “I’m sort of on the downslope of my career” as he finishes work on his longtime cohort of patients. “All of them are cured,” he said. “It’s so dramatic. It was the greatest thrill, to be involved with the cure of the first patient, then all subsequent patients. I could never have imagined this—not in my lifetime.”

He thinks a vaccine will be tough to develop, because the hepatitis C virus “is constantly mutating. You could kill the dominant strain, but another will come up and keep the infection going. It’s like HIV in that respect…It’s a tough fight. I’m not sure we’ll get to a vaccine. But we don’t need it to cure patients.”

Alter said Blumberg taught him an important early lesson: “If you find something unexpected, keep looking, keep persisting…We were allowed to do research at NIH, to look for something where you didn’t know where you were going. It couldn’t happen anywhere else. You don’t apply for a grant and say, ‘I want to discover a new virus.’ NIH offers the freedom to pursue things without having an immediate effect. Nowadays, it’s hard to get funding without an immediate [payoff]. We need to change that dynamic.”

Going forward, Alter said, the issues surrounding hepatitis C “aren’t really about science. We don’t need better drugs, or tests. We need the political will to eradicate it. We need to make drugs affordable. We need the will to do it, and it will take a global effort.”

Hepatitis C is still with us, still spreading, especially in the developing world, he warned. “It’s mostly shared needle use that keeps it going. We need to help the drug addict population. They should use disposable equipment, if they are still using drugs.

“In the third world,” he continued, “we need to teach health care workers not to use needles or vials over again; for them it is an economic issue. Test and treat is the key.”

A native of New York City, Alter earned his medical degree at the University of Rochester Medical School and trained in internal medicine at Strong Memorial Hospital and at the University Hospitals of Seattle. In 1961, he came to NIH as a clinical associate. He then spent several years with Georgetown University before returning to NIH in 1969 to be a senior investigator in what became the Clinical Center’s department of transfusion medicine. He later became chief of DTM clinical studies and associate director of research in the department. His current title there is senior scholar.

In 2000, Alter was awarded the Clinical Medical Lasker Award. In 2002, he became the first Clinical Center scientist elected to the National Academy of Sciences. That same year, he was elected to the Institute of Medicine. In 2013, Alter was honored with the Canada Gairdner International Award for his critical contribution to the discovery and isolation of the hepatitis C virus.

Photo: Bill Branson

Alter is the sixth NIH intramural scientist to win the Nobel Prize, which had not gone to a campus investigator since Dr. Martin Rodbell won in 1994. The other intramural laureates are Dr. D. Carleton Gajdusek (1976), Dr. Christian B. Anfinsen (1972), Dr. Julius Axelrod (1970) and Dr. Marshall W. Nirenberg (1968).

Alter’s co-laureate Rice has received continuous NIH funding since 1987, totaling more than $67 million, primarily from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

For more on the prize, visit https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2020/press-release/.