Copper’s Antimicrobial Properties Might Treat Bacterial Diseases

Photo: Mari Cleven

Doctors might one day use copper’s antimicrobial properties to treat bacterial diseases, said Dr. Michael D. L. Johnson at a recent NIGMS Director’s Early-Career Investigator Lecture.

“Copper is universally toxic to bacteria,” said Johnson, assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s department of immunobiology. “Our body uses copper to kill pathogens.”

For centuries, people have harnessed copper’s antimicrobial properties. They stored food in copper pots. Winemakers use a mixture of copper, slaked lime and water to control fungal infections on grapevines. In hospitals, copper doorknobs and bed frames can help reduce hospital-acquired infections.

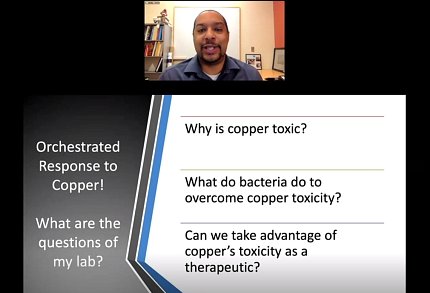

Johnson’s lab is studying how Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria, or pneumococcus, responds to copper. They are trying to answer the question: “If you punch bacteria with copper, how does it punch back?”

The bacteria cause many types of illness, including pneumonia, ear and sinus infections, meningitis and sepsis. There are two vaccines against pneumococcus, one for 13 strains and one for 23 strains. However, there are 100 strains and, for many, there are no vaccines. About 1.6 million people die each year from pneumococcus infection, mostly in developing countries.

S. pneumoniae has a copper export system to get rid of the metal quickly. The system features the proteins CopY, CupA and CopA. CopY prevents the system from turning on until it senses copper. CupA is a chaperone protein, meaning it guides copper to the exporter protein, CopA, which eliminates copper from the bacteria.

“A lot of these bacterial systems used to overcome copper stress can be used as therapeutic targets,” Johnson said.

Currently, he is trying to determine exactly how the system functions. In one experiment, he hypothesized that CopY is the master regulator of the export system. His experiments showed something different.

“A hypothesis can be proven incorrect. You should always try to prove it incorrect,” said Johnson. “Ultimately, you’re not defined by your hypothesis. If you weren’t correct, that’s okay—as long as you do the experiment to prove or disprove it and get data from it.”

He added: “You have to ask yourself, ‘Well, what are the assumptions that I made that were incorrect?’”

Although his hypothesis proved incorrect, he used the information from the experiment to continue investigating how to stop S. pneumoniae’s export system from functioning.

This past summer, Johnson created the National Summer Undergraduate Research Project, which matched 250 black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) undergraduate students with microbiology laboratory mentors who can provide remote summer research project experience.

He started the project because many BIPOC students missed out on research experiences due to the Covid-19 pandemic and due to potential bias in science.

“We’re very excited to move forward with this program,” he said. “We have to adapt the way we’re doing science, especially in these times.”

His lecture, aimed at those considering research careers, was followed by a Q&A chat with NIGMS director Dr. Jon Lorsch. NIH director Dr. Francis Collins introduced the talk.

Johnson received a B.A. in music with a minor in chemistry from Duke University. He said music gave him the confidence to pursue a career in science because “I was able to really learn how group dynamics work, as far as running a jazz band or being in a marching band.”

Additionally, he knew that, with hard work and practice, he could compete with more talented musicians in blind auditions. He thought he could bring that same mindset into another field.

When he was first hired to work in a lab, the researcher who hired him said, “You’re not the most qualified person for this job, but I figure you had a good ability to learn.”

In graduate school, Johnson’s apartment complex caught fire. The experience had a silver lining—it showed him what a supportive and welcoming laboratory looked like.

“My laboratory was there for me, my mentor was there for me, my department was there for me,” he explained. “People gave me their time, resources and effort. It created this family environment in the lab.”

During his time in school, he learned that not every scientific experience will be “joyful or pleasurable.” These experiences will, however, help “you define what type of researcher you might want to be.”

After Johnson opened his lab in 2016, he soon realized he wasn’t prepared for the human element of management. He advised those who might one day open their own labs to mentor others.

“Doing an experiment on the bench does not teach you how to deal with people. Coming up with a hypothesis does not prepare you to deal with people,” he counseled. “A lot of those things you learn on the fly.”

Finally, Johnson urged students to seek out allies who can help them, whether those are people of color or people of majority.

“Everybody is needed at the table for us to get through,” he said. “No one can do anything alone.”