Fast, Reliable, Universal

Corbett Recounts Quest for Covid Vaccine

Long before Covid-19 became a global crisis, scientists at NIH’s Vaccine Research Center were examining the fundamental mechanics of coronaviruses. Already the world had witnessed the damage SARS and MERS could do, and veteran virologists knew it was only a matter of time before the next threat emerged. VRC investigators had devised a strategy, however, and their proactive research provided a much-needed jumpstart in the race for a vaccine.

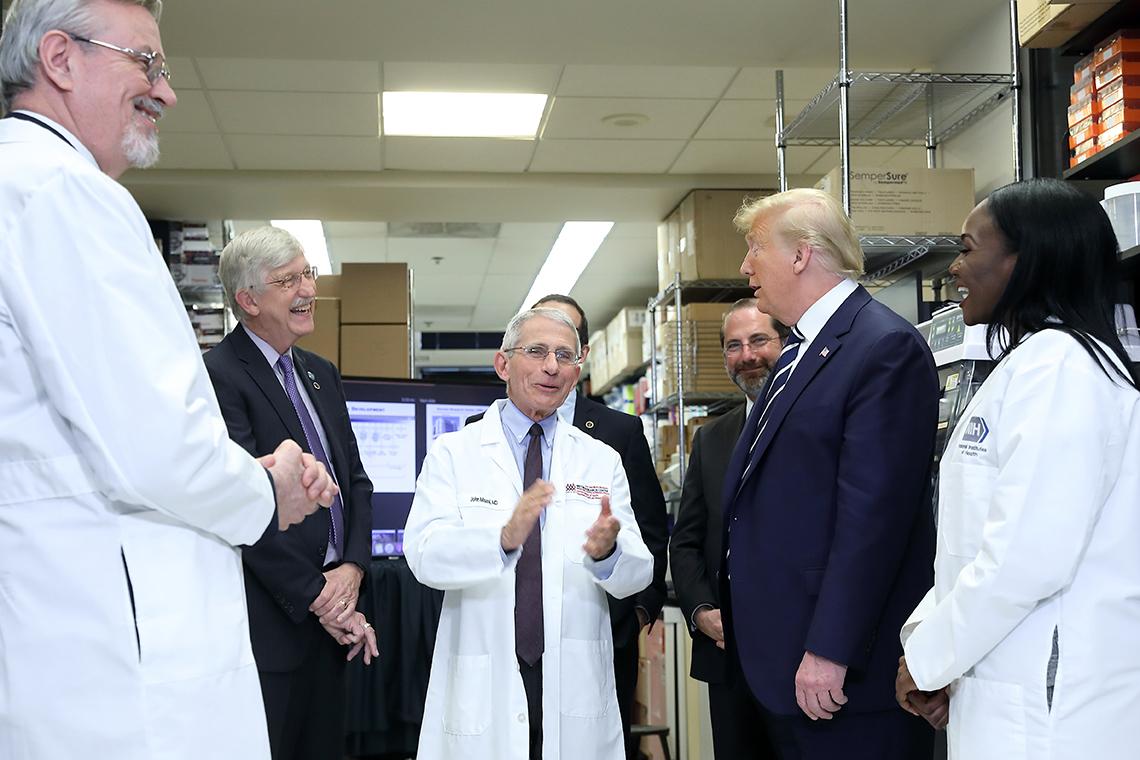

Recounting those efforts, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, a senior research fellow who’s spent the past 6 years working with VRC strategists in NIAID’s Viral Pathogenesis Laboratory (VPL) and who’s become a central figure in covid vaccine science, recently discussed “SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness.”

She said three key words describe her group’s approach—fast, reliable and universal.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“The way we think about coronavirus vaccine development is fairly simple,” Corbett explained during her recent virtual Covid-19 scientific interest group lecture.

“Because coronavirus is always poised for human emergence, we need a vaccine that is fast—something that has the technology to be produced in vast quantities very quickly…Also reliable—a technology that has been tested in humans and upholds some level of manufacturability standards…[and lastly] universal—not necessarily preemptive and totally protective against all future outbreaks, but something that could at least provide a ‘plug-and-play strategy’ if an outbreak should occur.”

Decidedly Fast

To appreciate how quickly the VRC vaccine made it to clinical testing, you have to look back at inoculation history and the stages of modern vaccine development. Often it takes 10 to 15 years to put a vaccine in place. The exploratory and pre-clinical stages alone can last up to 6 years or more. Covid-19 couldn’t wait that long.

“It goes without saying that the 2019 emergence of SARS-CoV-2 has been devastating—this pandemic has caused over 38 million cases worldwide,” Corbett acknowledged, describing the “prototype pathogen approach to pandemic preparedness.”

Using that method, she said, researchers choose “a prototypic virus from among the 24 viral families that have the potential to infect humans, study in depth the immunogenicity and development of a vaccine for one of the viruses in that family and [thereby] generate enough knowledge that can be applied widely across viruses within that family.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“The work we’ve done on SARS-CoV-2 is a proof of concept for that approach,” she continued. “I like to call it the plug-and-play approach, but the basic idea is that we had so much knowledge based on previously done work by ourselves and other labs that we were able to pull the trigger on vaccine development and start the ball rolling toward a phase 1 clinical trial.”

The Covid-19 respiratory illness outbreak was reported in Wuhan, China, on Dec. 31, 2019. On Jan. 10, researchers published the sequence of the novel coronavirus that causes covid; 66 days later, on Mar. 16, the VRC vaccine candidate “mRNA-1273,” which was developed in collaboration with biotech firm Moderna, entered phase 1 clinical testing in humans.

Determined Reliable

Corbett’s boss, VRC deputy director Dr. Barney Graham, a veteran virologist who also serves as VPL chief and an architect of NIAID’s Prototype Pathogen Preparedness Plan, introduced Corbett’s lecture.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“For the past 6 years,” he said, “her work has focused on coronavirus biology, especially spike structure, antibodies, mechanisms of neutralization and vaccine development…[her team] made the first spike protein that was the basis for diagnostic assays, antibody discovery and vaccines. She’s been central to the development of the mRNA vaccine and Lilly monoclonal antibody that were the first to enter phase 1 and phase 2 trials in the U.S.”

As the vaccine immunobiology unit’s team leader for coronavirus research, Corbett credited scientific groundwork for mRNA-1273’s virtual sprint to clinical trial.

VRC investigators and colleagues, she noted, were able to “use new technology to continuously transform vaccinology in both precision—by understanding structure-based vaccine design and protein engineering of nanoparticles, and speed—by employing different platforms to deliver the antigens that can be manufactured quickly, like messenger RNA.”

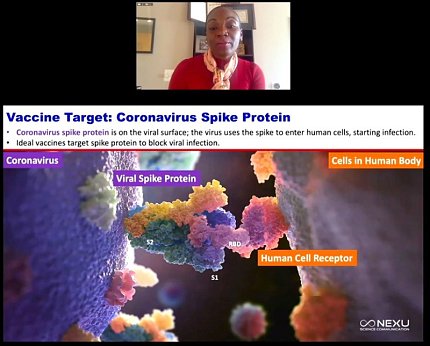

Corbett’s group chose the coronavirus spike protein as a vaccine target. The protein is located on the viral surface and the virus uses the spike to latch onto and bind to the host cell.

Designing ‘Universal’

Over the course of about 50 minutes, Corbett led viewers through the basics of coronavirus spike structure and function, and detailed the step-by-step research that led to the 2-dose vaccine known as mRNA-1273.

She also shared some positive initial findings from two phase 1 clinical studies: importantly, the vaccine, then in phase 3 efficacy testing, drew strong immune responses in both younger and older adults.

For Corbett and colleagues, however, a universal vaccine that can battle multiple coronaviruses on many different fronts remains their holy grail. Toward that end, she said her team foresees finding ways to optimize antigen designs so that they latch on to more potent immune system handles and to use gene-based delivery so vaccine manufacturing timelines can be shortened.

“While we were able to elicit robust responses [with mRNA-1273]…those responses were largely monospecific to the particular virus,” she concluded. “We have some hypotheses around that, but essentially as we think forward in coronavirus vaccinology, it’ll be important to not just start on the onset of a pandemic with what are universal strategies for vaccines, but to think outside the box to eliciting more cross-reactive and cross-protective immune responses.”

A brief Q&A session followed her talk. To watch the full lecture, visit https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=38864.