Cataract Surgery in Infancy Increases Glaucoma Risk

Photo: NEI

Children who undergo cataract surgery as infants have a 22 percent risk of glaucoma 10 years later, whether or not they receive an intraocular lens implant. The findings come from the NEI-funded Infant Aphakic Treatment Study, which recently published 10-year follow-up results in JAMA Ophthalmology.

“These findings underscore the need for long-term glaucoma surveillance among infant cataract surgery patients,” said NEI director Dr. Michael Chiang. “They also provide some measure of assurance that it is not necessary to place an intraocular lens at the time of cataract surgery.”

At the time of cataract removal, the 114 study participants (ages 1-6 months) had been born with cataract in one eye. In the operating room, the infants were randomly assigned to receive an artificial lens implant or go without a lens, a condition called aphakia.

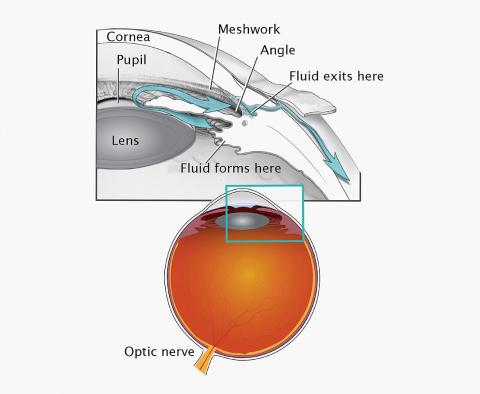

Annually, fewer than 2,500 children in the U.S. are born with cataract, a clouding of the eye’s lens. Surgery is used to remove and replace the cloudy lens. To allow the child’s eye to focus light properly following cataract removal, an intraocular lens implant may be placed at surgery, or the eye may be left aphakic, and a contact lens (or glasses, if both eyes have had a cataract removed) may be used to provide the needed correction.

Children who undergo cataract removal have an increased risk of glaucoma, a sight-threatening condition that damages the optic nerve—the connection between the eye and brain. Scientists speculate that surgery to remove the cataract interferes with the maturation of how fluid flows out of the infant’s eye, leading to increased eye pressure and optic nerve damage in some of these eyes.

After 10 years, 40 percent of the followed children had developed glaucoma or were glaucoma-suspect, due to elevated eye pressure. But due to close patient monitoring, any sign of glaucoma was aggressively treated and researchers found no evidence of glaucoma-related eye damage.

The findings also confirm that the timing of cataract surgery is a balancing act: Whereas surgery at younger ages increases glaucoma risk, delaying surgery increases risk of amblyopia, a leading cause of visual impairment in children.