a scientific jam session

Panelists Collaborate to Develop Toolkit for Music-Based Therapies

Performers and music lovers the world over will attest that music moves and rejuvenates us, affecting our brains in profound ways. But can investigators prove it?

Four years ago, world-renowned soprano Renée Fleming spent 2 hours in an MRI scanner that tracked her brain activity as she sang. The experiment was part of Sound Health, an NIH-Kennedy Center initiative that Fleming helped launch to study the impact of music on health and healing.

Since then, Sound Health has hosted performances, scientific workshops and community activities while also supporting investigative research into the science of music. Now, NIH’s music and health working group—a medley of scientific minds from across NIH—is orchestrating a toolkit to help researchers conduct rigorous music-based interventions for brain disorders of aging.

“The field has incredible potential to provide new insights into how our brain works, along with noninvasive and cost-effective treatments using creative arts therapies,” said Fleming, during a recent virtual gathering of researchers, clinicians, music therapists, patient advocates and creative arts representatives.

It was the first of three meetings—a prelude to start hammering out the components of the toolkit—in this new phase of Sound Health, in partnership with the Renée Fleming Foundation and the Foundation for the NIH. The 26 panelists spent the afternoon developing guidelines and methodologies to spur rigorous, data-driven research on the impact of music on health.

“Musicians and creative arts therapists have, through personal experience, always been aware of the holistic value of music for healing,” said Fleming. “But to improve and expand individualized care, and engage the support of policymakers, insurers and health care institutions, we need this incremental process of research to solidify knowledge of the concrete impacts of music on health.”

In welcoming this working group session, Fleming said she’s excited to take part in this process, hopeful the research could yield therapies that will improve millions of lives. “I hope to keep singing this to the rafters in the coming years,” she said.

Three sponsoring institutes are also singing its praises. NIA director Dr. Richard Hodes underscored the potential of music therapy to help treat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, stroke and other disorders of aging. There’s great interest in finding effective interventions that could intercept neurodegenerative processes and maximize quality of life with age.

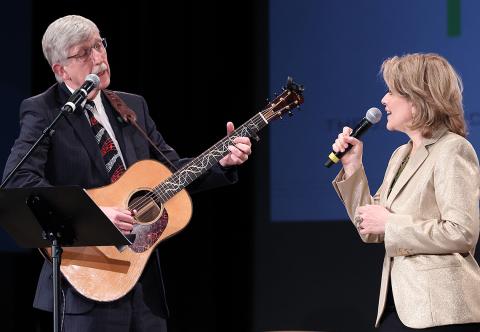

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

This initiative is also an opportunity to study the therapeutic benefits of music across the lifespan. “Many of us at NINDS have been hypothesizing that…engaging with music during early life may in fact build the resilience that allows one to thwart the forces that would lead to neurodegeneration in aging,” said NINDS deputy director Dr. Nina Schor. The goal is “not just to treat [these] disorders, but also to prevent them in the first place.”

Music therapy has little risk of negative side effects. It’s a natural, nonpharmacological intervention with the potential of becoming more integrated into mainstream health care, said NCCIH director Dr. Helene Langevin. “Singing and playing a musical instrument clearly involves both the mind and the body.”

Even listening to music, or thinking about music, can have physical and psychological effects. Interestingly, when Fleming was in the MRI machine, the scans showed her brain was most active not while singing or talking, but while imagining she was singing.

Music may have medicinal powers, but don’t make assumptions to fit your hypothesis, cautioned NINDS program director Dr. Shai Silberberg.

A particular intervention may benefit some study volunteers, but what if some participants are tone deaf or hard of hearing? Will the intervention be therapeutic if the subject is tasked with listening to opera but—gasp—(apologies to Fleming) despises that musical genre?

In designing studies, beware of unintentional bias, said Silberberg. He cited a decades-old psychology study in which students were told certain rats were bred to be smarter. The students repeatedly found those rats to be fastest at their task; but there were no trained rats.

“There was expectation bias on the side of the students,” he said. “They expected the bright rats to learn faster, so that’s what they found.”

Silberberg said his toolkit would include a mirror, a balance, blindfolds, dice and a statistician. The mirror is to reflect on unconscious biases; the balance represents taking measures to minimize their impact. Blinding all participants in a clinical trial can prevent expectation bias, he said. Randomizing participants among the groups can increase the chance that comparison groups are balanced. But be careful how you roll the dice.

In a pilot study on music therapy to enhance mobility for Parkinson’s patients, investigators randomized the participants. The test group was exposed to specific life activities and received multiple music sessions per week, while the control group did not participate in the music or activities. Was the music itself beneficial and restorative? The study was inconclusive.

“We should do our best to adjust the groups to be equal except for the one intervention being tested and, importantly, try to use objective, reliable outcomes,” advised Silberberg.

Aim for transparent data, he added, and large effects that make the research worth pursuing and may attract broader support.