Unraveling Health Disparities

Valantine Discusses Genomics in Organ Transplantation

A decades-long career in medicine and research never occurred to an adolescent Hannah Valantine. Born in Banjul in the small West African nation of The Gambia, 13-year-old Hannah and her family relocated to London, where she was the only youngster of color in her high school. Within a student population of 500 adolescents, her sense of isolation took a toll.

“My academic struggles at age 18 were such that I had zero aspirations to go to university,” recalled Valantine at a recent Clinical Center Grand Rounds. “[High school] was my first encounter with being excluded. I attribute the lapse in my career path to my feelings of being excluded.” That and other teen distractions at the time—“the Swinging Sixties, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles”—also may have contributed to her less than enthusiastic embrace of textbooks.

“That’s my story and I’m sticking to it,” Valantine quipped, smiling.

A job in a microbiology lab put her back on an achievement-filled educational trajectory that has led to an M.D. degree, cardiology fellowship at Stanford University, her own lab and principal investigator authority on numerous grants, authorship of 200-plus peer-reviewed publications and more than 30 years pursuing medical research as a full-time profession.

No stranger to NIH, Valantine served for 6 years since 2014 as the agency’s first chief officer for scientific workforce diversity while also maintaining a lab as a senior investigator in NHLBI’s intramural research program. She returned to her post as professor of medicine and cardiology at Stanford Medical Center in spring 2020.

In her NIH virtual lecture, “Inclusive Excellence in Biomedical Research—Applying Genomics to Unravel Health Disparities in Organ Transplantation,” she used evidence from some of her NHLBI clinical studies on organ rejection to make the case for diversity in the scientific workforce. Arguably, Valantine’s own career could be Exhibit A.

It was at Stanford in 1985 that she first became “fascinated by the idea of transplantation”—extracting an organ from a deceased person and getting it to work effectively in a living person. “Quite frankly, I’m still in awe of the idea,” she admitted.

Valantine gave several reasons that the world’s biomedical investigation workforce ought to include professionals and trainees from diverse racial, ethnic, minority and underserved communities: To achieve excellence in research, improve the quality of patient care and expand participant inclusion in clinical research.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“All of these are in the NIH mission,” she noted.

Valantine cited journal articles documenting the impact of diversity. Physicians from underrepresented groups in medicine are twice as likely to work in underserved communities. Patients are twice as likely to adhere to recommendations and advice—about diabetes, cholesterol screening, flu shot, for example—from physicians of similar racial and ethnic backgrounds.

In addition, she noted, “physician-scientists are more likely to focus their research on topics/diseases that disproportionately affect their communities.”

The quality and applicability of clinical research, including clinical trials, increase when the investigator and patient populations are diverse, Valantine pointed out.

“These factors put together point significantly to reducing racial disparities in a wide spectrum of disorders, including hypertension, cancer, diabetes, maternal and infant mortality, Covid-19 and organ transplant rejection,” she said.

Turning to her own specialty—organ transplantation, specifically development of chronic heart rejection—and the focus of her recent research, she set out to answer a series of questions: What is the role of genetic distance between donor and recipient? Is the organ rejection due to mitochondrial DNA mismatch, even when the genetics of the nuclear DNA are absolutely identical? What might be the contribution of social determinants of health?

About 10 years ago before coming to NIH, Valantine initiated a collaboration with preeminent Stanford geneticist and biophysicist Dr. Steve Quake, who developed diagnostic technologies using next generation sequencing. The Valantine and Quake groups worked together on a technique to identify potential signs of organ rejection using donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) in solid-organ transplantation.

“We were able to do the proof-of-concept experiments and publish a range of articles indicating that indeed [dd-cfDNA] was a significantly important marker of graft injury and therefore rejection.”

Subsequently, Valantine and colleagues were able to use the technology to predict which transplant patients might develop an infection, which is one harbinger of organ rejection and poorer survival.

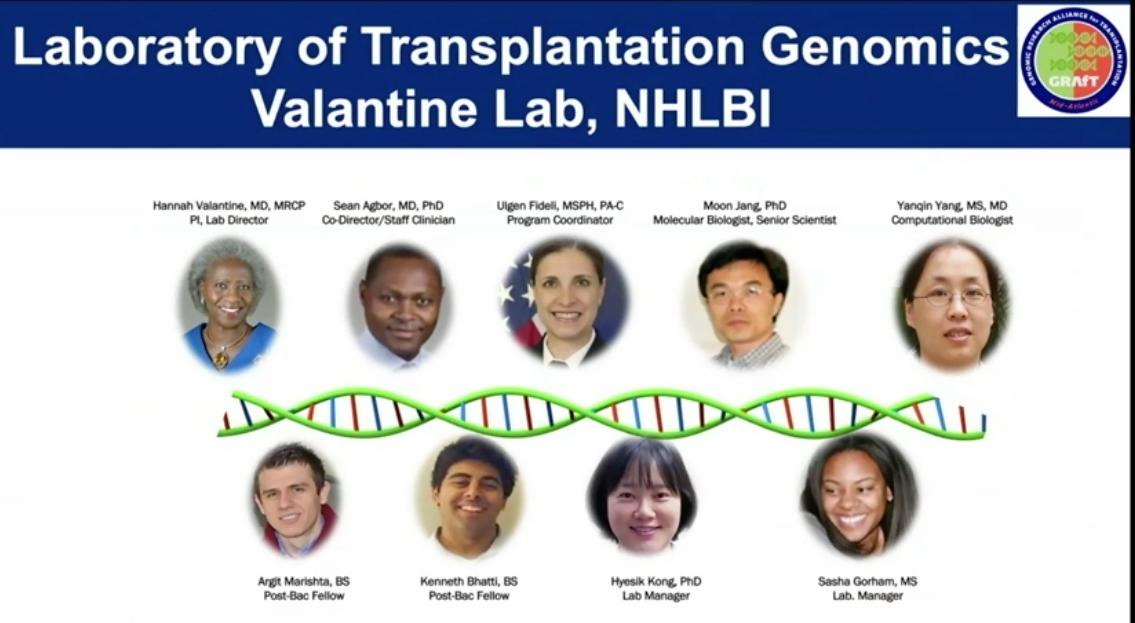

The Valantine Lab at NHLBI, the Laboratory of Transplantation Genomics, teamed with other like-minded investigators to establish GRAfT, the Genomic Research Alliance for Transplantation, a collaboration with health care organizations that offer organ transplantation and organ procurement centers. GRAfT provided measures of reproducibility and research rigor, in addition to mechanisms for long-term follow-up of patients. GRAfT also recruited a disproportionately large number of African Americans; that rare patient enrollment profile gave researchers a unique cohort to study how social determinants of health might impact diagnoses of problems related to organ transplantation.

Using the technology developed by Valantine’s team, investigators were able to detect signs of organ rejection 3 months before biopsy.

“This becomes very important,” she explained, “because it gives us the opportunity to act and treat those patients before they progress to chronic rejection” and poorer survival risk.

GRAfT results also revealed that Black transplant patients show evidence of the dd-cfDNA marker as early as the day after transplant. Importantly, levels of dd-cfDNA in Black patients remained higher than in White patients throughout the follow-up period, despite equivalent blood levels of the anti-rejection drugs.

“This eliminates the idea that [organ rejection in Black patients] is in some way related to non-compliance with medications or different metabolism of immunosuppressive drugs,” Valantine explained.

Conclusions drawn from GRAfT have led to a host of new questions to answer and avenues of research to explore, she pointed out.

“Which brings us all the way back to who is going to be doing this work and why attention to the scientific workforce—and the diversity of perspectives embedded in the scientific workforce—is so critically important…Our work is really cut out for us to achieve equity at all academic levels. Individual interventions are not sufficient to take us where we need to go. We must continue with institutional interventions…that means transparency and accountability as well as systematic review of hiring and promotion policies…The most important thing I learned from my time at NIH is that we must be linking the diversity and equity work to institutional reward systems.”

Valantine closed by countering the popular thought that great minds think alike. “Great minds think differently,” she emphasized, using oft-quoted words from Einstein to end: “‘We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.’”

Watch the full lecture with Q&A at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=41679.