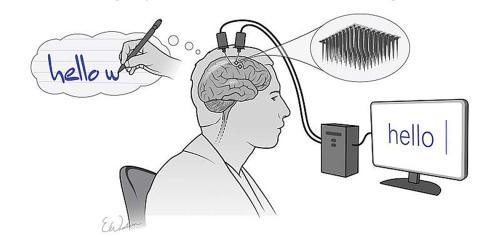

Turning Imagined Handwriting into Text

Photo: ERIKA WOODRUM (ARTIST), SHENOY LAB

Researchers developed a system that quickly translates brain signals for handwriting into text. While preliminary, this technology could help people with spinal cord injuries and neurological disorders who have lost the ability to write and speak to communicate.

The study, funded by NIH’s BRAIN Initiative, as well as NINDS and NIDCD, appeared online in Nature.

Brain-computer interfaces, or BCIs, enable a direct link between the brain and an external computer. Using BCI technology, people who are paralyzed can control a robotic arm or type with a computer cursor. But point-and-click typing using BCIs can be a slow process, making it inefficient to use.

In the new study, researchers developed a BCI that translates thoughts of handwriting movements into text in real time. They assessed the speed and accuracy of the system with a person who was paralyzed from a spinal cord injury. The participant was told to imagine he was holding a pen on a piece of ruled paper. He attempted to copy letters displayed on a screen, as well as symbols for spaces and stops, as if his hand was not paralyzed.

Electrodes implanted in the brain recorded activity from roughly 200 neurons that responded to the “writing” of each character. A machine-learning algorithm used these signals to learn to identify the neural patterns representing individual letters. After a series of training sessions, the system allowed the participant to form new sentences, with the computer displaying letters in real time.

Using the new system, the participant could compose sentences at about 90 characters per minute with 94 percent accuracy. This speed is comparable to someone of a similar age typing on a smartphone. In contrast, “point-and-click” interfaces have only achieved about 40 characters per minute.

“This study represents an important milestone in the development of BCIs and machine learning technologies that are unraveling how the human brain controls processes as complex as communication,” said Dr. John Ngai, director of the NIH BRAIN Initiative. “This knowledge is providing a critical foundation for improving the lives of others with neurological injuries and disorders.” —adapted from Research Matters