Developing a New Kind of Temporary Pacemaker

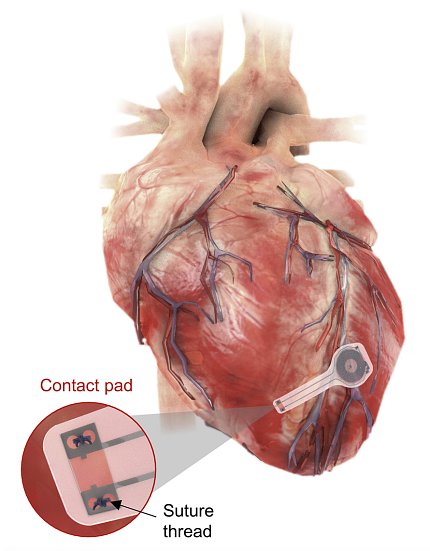

Photo: Northwestern/GWU

Researchers developed a wirelessly powered temporary pacemaker that breaks down in the body after use. The device can generate enough power to pace a human heart without causing damage or inflammation. The findings appeared in Nature Biotechnology.

Pacemakers send electrical pulses to help the heart beat at a normal rate and rhythm, or to help the heart chambers beat in sync. Sometimes people only need a temporary pacemaker, which uses wires connected to a power source outside the body.

But temporary pacemakers can cause complications, including infection from the wires crossing the skin, scar tissue formation and damage to the heart upon removal.

Now, researchers have built a new pacemaker entirely from components that break down in the body over time. The device gets power using technology like that used for wireless charging of portable electronic devices.

“Our wireless, transient pacemakers overcome key disadvantages of traditional temporary devices and eliminate the need for surgical extraction procedures,” said lead author Dr. John Rogers of Northwestern University.

The team first tested the new dissolvable pacemaker in heart-tissue samples taken from mice, rabbits and people. In these samples, the device could absorb and transmit enough power to control the rhythm of either the upper or lower chambers of the heart.

When implanted in live dogs, the pacemaker absorbed enough power to control the heart’s rhythm. This required the wireless charger to be about 6 inches from the chest or closer. The power generated was equal to that required to pace a human heart.

For longer-term studies, the team implanted smaller versions of the device into rats. The pacemaker was able to control the heart’s ventricles for 4 days after surgery. After that, its function began to break down. Using serial CT scans, the team found that the pacemakers broke down entirely in the body by the seventh week after surgery.

Further analysis of the scans showed that heart tissue was unharmed by the device. Blood tests also found no signs of inflammation. Further work will be needed before testing in people.—adapted from NIH Research Matters