‘A hard pivot’

Sadtler Pauses Tissue Engineering Project to Launch Antibody Protocol

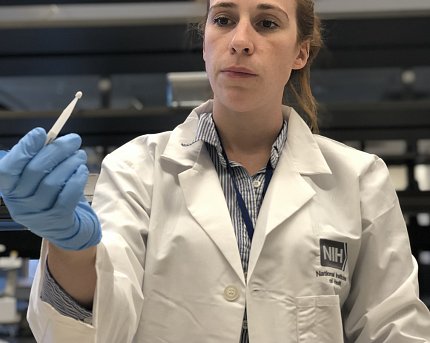

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Dr. Kaitlyn Sadtler arrived at NIH in September 2019, energized to study ways to regenerate injured tissues. She had her laboratory set up, ready to go in January 2020 but, 2 months later, when the pandemic struck, she soon found herself working on a completely different project.

“It was very much a hard pivot,” said Sadtler, an Earl Stadtman tenure-track investigator and chief of NIBIB’s section for immunoengineering. “I didn’t plan for infectious disease to be the main part of my lab. I had to change my mindset to start developing serologic assays for processing antibody tests.”

The new project began with scientific curiosity and some chitchat. Wouldn’t it be interesting to evaluate asymptomatic Covid infections, wondered Sadtler and NCATS colleague Dr. Matthew Hall over Twitter, of all places. Could they study people with potential undiagnosed infections? “Sure! We can do ELISAs!” she told Hall.

An ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay) is a common lab technique to measure viral proteins and antibodies. A robotic setup can automate the steps to increase testing capacity.

“Little did I know that was a huge commitment on my end,” Sadtler said. It required temporarily casting aside her original project. “But go big or go home, I guess!”

Sadtler and Hall connected with NIAID clinicians and soon launched the Covid protocol, enrolling 11,000 people nationally to test for Covid antibodies at multiple time points. In the collaboration among NIBIB, NCATS, NIAID and NCI’s Frederick National Lab for Cancer Research, study participants received home-testing kits and mailed their dried blood samples to Sadtler’s lab for analysis.

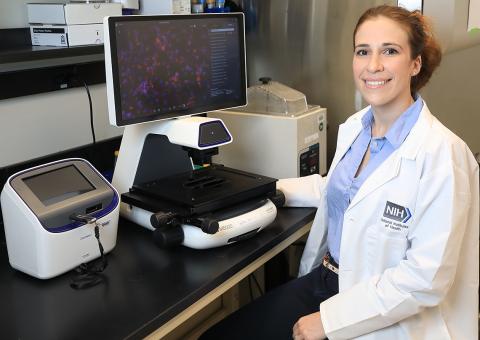

Photo: NIBIB

It was almost fate that Sadtler came to work on a Covid project. Before the pandemic, she did her postdoctoral fellowship in immunology and bioengineering at MIT with Dr. Robert Langer, a cofounder of Moderna. There, she learned a bit about nanoparticle therapies and mRNA vaccines.

During her time in Boston, she connected with investigators at the Ragon Institute, one of whom was doing antibody testing research.

“So, while I was in the co-founder of Moderna’s lab for my postdoc, I met somebody we’d [later] collaborate with to get an antigen construct to do our serology work down here at NIH,” Sadtler said. “He wound up happily sending us the plasmid for the protein, and that’s the one we used.”

The biggest challenge early on was a technological one. “We were running so many assays, we broke the [ELISA] robot!” said Sadtler. A couple of replacement parts later, it was back up to speed.

“We’re going to learn a lot from this study beyond just the proportion of people with antibodies,” she said. Along with sending physical specimens, each participant answered demographic, health and vaccination questions.

From all of this, Sadtler and the team of NIH scientists hope to gain more insights about the geographic distribution of Covid and about antibody decay rates, since the study follows the same people over time. Did people with asymptomatic infections have vaccine reactions? Are antibodies from prior infection protective against Covid variants?

“We can correlate all of this within the subgroup analyses of different demographics, geographics, health and socioeconomic factors,” she said.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

As all the specimens and demographics rolled in and the assays were run, Sadtler found help managing and interpreting the large datasets from NIAID statisticians. “They do math that’s far beyond me,” she said.

Now, Sadtler is continuing this protocol while resuming her original project, studying how the immune system—which gets activated to prevent infection—can help build back damaged tissue following injury. Ultimately her group is working toward developing new materials and medical devices that can heal wounds faster.

She’s also helping with 2 related projects: 1 looking at antibody responses in patients with rare diseases, and another working with 6 trauma centers to study infectious diseases, including the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, among trauma patients.

Sadtler’s unexpected pandemic project started with curiosity and took her on a research journey that kept getting bigger.

“I do think it shows the strength of having an interdisciplinary research community,” she said, “so individuals coming in with, say, a bioengineering background [could apply their skills where needed during the pandemic]. Ultimately, it’s that interdisciplinary nature of research that drives things forward.”