Blocking Hormone Reduces Alzheimer’s Symptoms in Mice

Photo: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Women have a higher risk than men for developing Alzheimer’s disease and experience a broader range of cognitive symptoms—those related to thinking, learning and memory. The disease also tends to progress faster in women.

These gender differences have led researchers to study whether hormones play a role. A team led by Dr. Mone Zaidi of Mount Sinai and Dr. Keqiang Ye of Emory University has been examining the many roles a hormone called follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) plays in the body.

FSH levels rise sharply in women around the time of menopause. In previous work, researchers found that blocking FSH in mice can prevent weight gain and reduce bone loss—two other common changes in women’s bodies during and after menopause.

In a new study, the team investigated whether FSH is involved in the development of Alzheimer’s. Funded in part by NIA, the research was published in Nature.

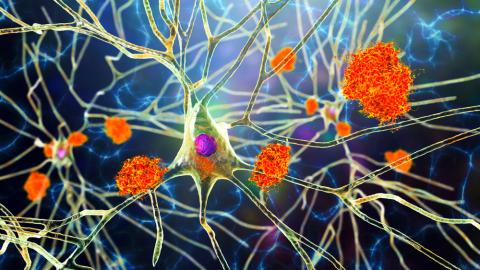

The lab team first put mice engineered to develop Alzheimer’s disease into a menopausal state. Levels of FSH rose in the blood of these mice. They also had accelerated cognitive decline and a buildup of amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles in their brains, which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

When the researchers gave the mice an antibody that blocked FSH, these effects were much less severe. Male mice, which produce some FSH, treated with the antibody also had less amyloid beta build-up in the brain.

In addition to the work in mice, the team found receptors for FSH in tissue samples taken from human and rat brains. Further work showed that that FSH can cross the blood-brain barrier and bind to these receptors on nerve cells.

The team has developed an antibody to block FSH in people and, after safety testing, hopes to test it in clinical trials for the prevention of Alzheimer’s as well as bone loss and obesity.

—adapted from NIH Research Matters