Painful Expectations

Atlas Investigates the Role of Placebo in Pain Management

Many of us have heard of the “placebo effect,” a beneficial health outcome resulting from a person’s anticipation that an intervention will help. Placebo effects tend to be the strongest in pain, leading researchers such as Dr. Lauren Atlas to wonder how the phenomenon might be harnessed to offer more effective pain relief.

Atlas, chief of the Affective Neuroscience and Pain Laboratory at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), also holds joint appointments with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Her lab focuses on characterizing the psychological and neural mechanisms by which expectations and other cognitive and affective factors influence pain, emotional experience and clinical outcomes.

In her recent Director’s Seminar series lecture, “Neural and Psychological Influences on Pain and its Assessment,” Atlas sought to understand how psychological factors shape pain.

“More than 30 million people in the U.S. live with some form of chronic or severe pain—more than cancer, heart disease and diabetes combined,” she said. Atlas believes psychologists such as herself can offer insights into understanding the relationships between pain, social processing, decisions and more.

“We think the placebo effect depends on the combined psychological processes of expectations for pain relief, shifts in emotions (like less anxiety) and the actual interpersonal social treatment context,” Atlas explained. By both manipulating and measuring each of these processes, she can isolate their effect on pain, and possibly answer other key questions about where and how it happens in the brain.

Atlas elicits pain responses in the lab using a thermode—a computer-controlled device that heats up and can cause mild pain. Each volunteer creates their own pain tolerance scale, with ratings one through 10, but they only experienced intensities they identify as tolerable (up to level eight) in follow-up experimental trials. In order for each volunteer to participate in further experimental trials, they had to be consistent in their self-reported scoring.

Several of Atlas’s postbac fellows analyzed the data of participants who had returned for multiple visits. Overall, these participants were reliable in their scoring of pain threshold and tolerance but, interestingly, the investigators found women were more reliable than men across all measures and across all visits.

“These findings contradict the assumption that female participants will be less consistent due to hormonal factors,” Atlas said. Instead, one might ask “Why are men more variable?”

After establishing her pain elicitation model, Atlas moved to the next step: looking to identify pain biomarkers. Brain imaging such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is one promising method. Atlas and her colleagues developed a statistical classifier model called the Neurologic Pain Signature (NPS), which measures brain activity associated with pain and uses those signals to predict pain intensity.

In an fMRI study, participants experienced heat or liquid solutions with an unpleasant or pleasant taste (different concentrations of salt or sugar, followed by a neutral rinse). During an initial visit, participants experienced all stimuli and were asked to rate their level of pain and also the perceived intensity of the taste they experienced. Interestingly, participants with a higher heat tolerance could also tolerate higher concentrations of salt and sugar. When two negative stimuli occur together, Atlas said, we can use classifiers such as the NPS to distinguish their separate contributions. Indeed, when a postdoc in Atlas’s group, Dr. Yili Zhao, compared the NPS response to painful heat to equally intense salt, she found that the NPS showed greater expression in the heat group, confirming specificity to pain.

With these baselines established, how can placebo shape pain and emotional reactions?

In the first test, patients received either a control cream or a “potent analgesic,” both of which were actually inert. The patients were conditioned to expect a certain pain stimulus—high intensity for the “control” and low intensity for the “potent analgesic”—and then both groups received a moderate intensity pain stimulus in the test phase.

Upon analysis, the fMRI scans showed “reliable reductions in pain,” but there appeared to be no placebo effect on the NPS. “This suggests placebos are reducing pain,” Atlas said, “but not via changes in the NPS.”

Other areas of interest are the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and nearby ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC). “These regions are hubs that receive input from limbic and sensory areas, and they also project to other areas of the brain critical for affective processing,” Atlas explained.

In short, this brain region is fundamental for prediction, expected value and learning. To study the OFC/VMPFC’s response to pain, patients were taught to expect certain pain levels when predicted by certain auditory cues. Next, in a test phase, patients either experienced the auditory cue with the matched pain (low or high), or an auditory cue with medium-intensity pain.

When the moderate pain was preceded by the low-pain cue sound versus the high-pain cue sound, Atlas found, the reported pain readings showed “reliable reductions” of about 20%. “We’ve seen over and over again that the OFC is critical for this type of cue-based expectation and pain modulation,” she said.

Atlas also examined the data from the study comparing pain with salt and sugar in the context of the VMPFC, and saw similar reductions in the intensity ratings and shared responses to predictions in the VMPFC across all three types of stimuli.

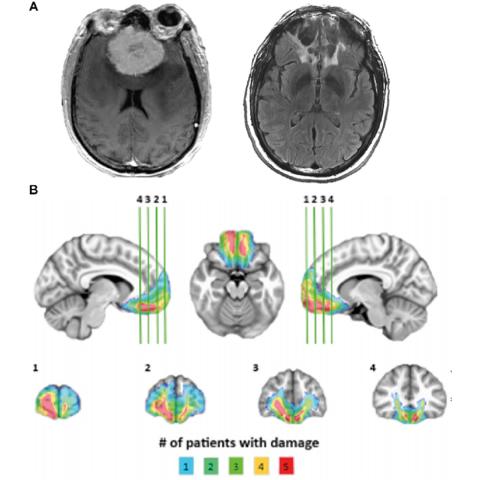

Finally, she compared five patients who had surgical lesions of the VMPFC (due to orbital meningioma tumors) with 20 healthy controls. All participants underwent the same pain calibration procedures from the earlier trials, but the VMPFC lesion patients seemed to experience stronger placebo effects than the healthy controls.

“VMPFC lesions enhance expectancy effects on pain, particularly pain unpleasantness,” summarized Atlas.

She also presented findings on social influences on pain expectations and assessment. The more similar a prospective provider looked to a patient, for example, the less pain the patient expected to experience during a medical procedure.

Racial biases are an obstacle patients may face when seeking treatment for pain. Research conducted by Atlas showed that volunteers were less likely to report facial expressions as painful when the target was Black, and even more so when the target was a Black male. However, she also found that volunteers improved their accuracy when they got to see the target’s own pain assessment.

Ultimately, Atlas said, we still have much to learn about the placebo effect and ways to improve patient pain outcomes. “Placebo analgesia seems to reflect shifts in emotion, learning and expectations, rather than changes in physiological signals, but this doesn’t mean placebo effects aren’t real,” she summarized. “Shifting someone’s anxiety can have real effects on their health.”

A recording of the lecture can be viewed here: https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=55366.