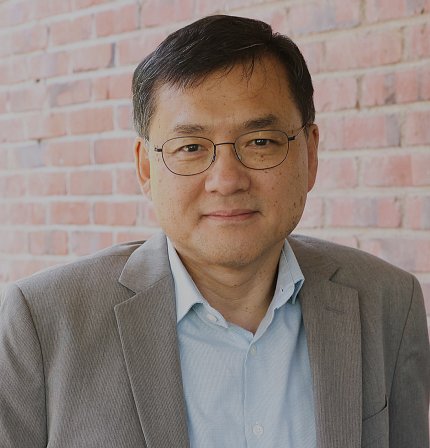

Historian Remembers NIH’s Role in the Asilomar Conference

Fifty years ago, a group of scientists, journalists and lawyers gathered at the Asilomar Conference Center on California’s Monterey peninsula to discuss potential biohazards and regulation of recombinant DNA research.

What resulted from the meeting was a set of NIH guidelines that ensured scientists could conduct this research under federal oversight, said Dr. Buhm Soon Park, professor and director for the Center for Anthropocene Studies at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) during a recent lecture in Lipsett Amphitheater.

The contributions of NIH scientists were essential in shaping the responsible conduct of recombinant DNA research, he said. They played crucial roles in the lead up to the conference and in the aftermath.

More than 140 biologists and physicians, and about 10 journalists and lawyers, came to Asilomar at the request of Stanford University biochemist Dr. Paul Berg and other members of a special committee of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).

The conference is now “known to be the key moment of modern biotechnology developing in a responsible way,” Park noted. It established the precedent for self-regulation in science.

Back in 1972, Berg and his colleagues were the first scientists to create a DNA molecule made of parts from different organisms, creating recombinant DNA. In the experiment, he inserted DNA from the bacterium E. coli into the animal virus SV40.

Berg’s peers had concerns about recombinant DNA research. Some believed it was too dangerous to be allowed to continue. They were worried the research would lead to the creation of new plagues and interfere with evolution. Park said one scientist called the idea to genetically engineer DNA “a pre-Hiroshima condition.”

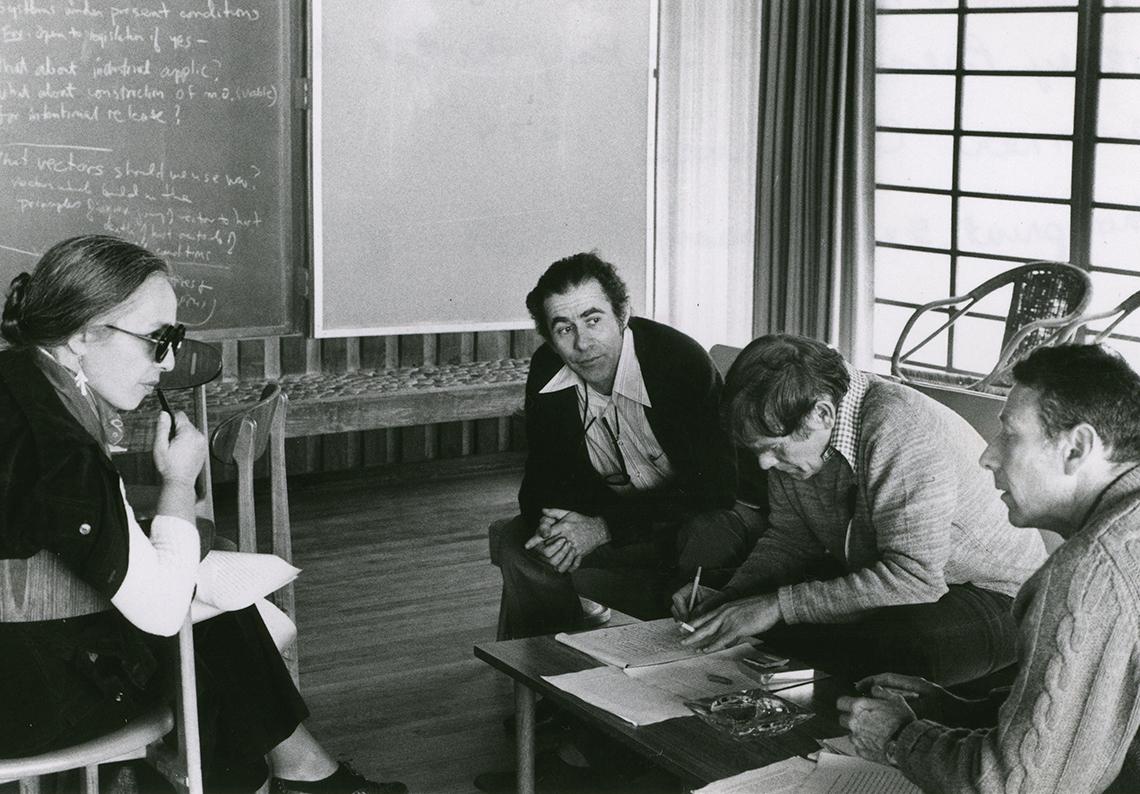

Photo: The Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum

In response to the controversy, Berg consulted with NIH scientists about the potential risk of genetically engineering DNA. He met with Dr. Maxine Singer, a lab chief in what was then the National Institute of Arthritis, Metabolism and Digestive Diseases and her husband, Daniel, a lawyer. He also visited with NIH scientists at the now demolished Bldg. 7, known as Memorial Bldg., including Dr. Andrew Lewis of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Dr. Berg was no stranger to NIH,” Park said.

A year later, a group of scientists led by Singer published a letter in Science asking the NAS president to establish a committee to consider the risks and benefits of recombinant DNA research and recommend specific guidelines.

At Singer’s recommendation, the NAS appointed Berg to head an ad hoc committee to study the biosafety of recombinant DNA research. The committee concluded they should organize a conference to review progress, which NIH would help fund.

A self-imposed moratorium on most recombinant DNA experiments went into place until safety concerns could be addressed. After the moratorium went into effect, NIH formed a recombinant DNA advisory committee.

Dr. DeWitt Stetten Jr. and Dr. Leon Jacobs co-chaired the committee, which included expert intramural scientists. The committee has since played a significant role in formulating guidelines and advising the NIH director on recombinant DNA technology.

Photo: NIH’S NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

With Singer’s help, Berg organized the Asilomar Conference. On the final day, attendees released a summary statement. Following the conference, NIH’s recombinant DNA advisory committee held several meetings to draft and finalize guidelines for minimizing the safety risks based on the summary statement.

Former NIH Director Dr. Donald Frederickson announced that all NIH-funded and conducted research involving recombinant DNA must follow the guidelines.

NIH scientists participated in public discussions and debates about the safety and ethical implications of recombinant DNA research, Park said. Singer, for instance, testified at a city council meeting in Cambridge, Mass. to address public concerns.

Earlier this year, Park attended the “Spirit of Asilomar and the Future of Biotechnology” summit, which revisited the legacy of the 1975 conference and addressed contemporary issues in biotechnology.

More than 300 attendees gathered at the same conference center in California to focus on five key themes: pathogens research and biological weapons, artificial intelligence and biotechnology, synthetic cells, biotechnologies beyond conventional containment and framing biotechnology’s future.

Of the summit’s attendees, only one worked at NIH. That struck Park as odd, considering the critical role NIH employees played during the 1975 conference. During the conference, Park saw photos of Singer and Stetten. To his knowledge, however, their contributions weren’t mentioned.

During this period, NIH navigated “turbulent waters of political and social conflict” while maintaining the integrity of science. NIH’s role in history must not be forgotten, he concluded.

Park’s lecture was part of the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum’s seminar series, which features lectures, interviews and panel discussions with scientists, historians and experts from different backgrounds and viewpoints. Their topics focus on events, people and policies from NIH’s inception in 1887 to the present. The 2025-2026 program begins this month.