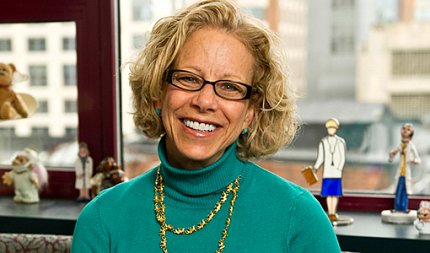

Five Questions with New NICHD Director

Dr. Diana Bianchi joined NIH as director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development on Nov. 7. She comes to NIH from the Floating Hospital for Children and Tufts Medical Center in Boston, where she served as founding executive director of the Mother Infant Research Institute and vice chair for pediatric research.

She recently answered some questions about her goals as she takes on this new role.

Why did you want to become NICHD director?

I always have been passionate about advancing knowledge to help people. Although I really enjoy taking care of patients and families, I realized early on that I could have a much bigger impact on health care through research. I am fortunate enough to have seen one of my basic research projects advance into medical practice. That project—isolating fetal cells from the blood of pregnant women—is now a noninvasive test for screening placental DNA that has been used by millions of women. While it is gratifying to see the clinical benefit of this test, I felt I could have an even greater influence on the lives of children and families by joining NIH and helping to shape a global research agenda.

NICHD’s broad mission offers a range of opportunities for multidisciplinary and longitudinal approaches to the research portfolio. I believe that my clinical training in pediatrics, medical genetics (including care of people with physical, intellectual and developmental disabilities) and neonatology, as well as my research expertise in reproductive genetics and genomics and fetal care, align well with the mission.

My concerns about federal research funding and the loss of talented people from the academic pipeline also played a role in my decision to join NICHD. I am dedicated to the training and mentoring of students, residents, postdoctoral fellows and faculty and I wanted the opportunity to work with leaders at NIH, as well as with those in the pediatric, obstetric, gynecologic and rehabilitation communities, to improve prospects for academic investigators looking to advance their careers and make a difference.

Another important factor in my decision was the lure of public service. As the child of immigrants who came to the United States before and after World War II, I wanted to give something back to the country that sheltered my family and provided us with economic and educational opportunities. A lot of that inspiration comes from my grandmother, who after escaping the Nazi invasion of Austria, settled in New York City and immediately volunteered to drive an ambulance. I want to continue that legacy of service.

What are your goals for NICHD?

Because science evolves so rapidly, we must be flexible enough to reorder our priorities in response to scientific opportunities and emerging public health needs. For example, today the congenital defects associated with Zika virus infection are a significant and immediate concern. Researchers funded by NICHD can and should contribute to an understanding of the basic mechanisms that result in microcephaly and more subtle fetal anomalies, as well as those that affect fertility and sexual transmission of the virus in adults. Furthermore, NICHD researchers can contribute to better and more accurate ways of detecting the virus and preventing its spread.

Another priority is to increase representation in clinical research of the populations that NICHD serves. I have had many pregnant women participate in my research and I can affirm that they are very interested in their bodies and their child’s development. Expectant mothers are likely to be enthusiastic participants in broader clinical research and children can benefit enormously from the knowledge generated by clinical studies. Lastly, we need to include people with disabilities as participants in research to not only obtain important information about an understudied group of people, but also to send a powerful message of inclusion.

Among other goals, I aim to enhance NICHD’s focus on basic and translational research in reproductive and neonatal genomics, which can help define the roles of genes in infertility, reproductive disorders and birth defects. I am very excited about using big data to develop innovative approaches and solutions to problems in NICHD’s research areas. I also will continue to support NICHD’s ongoing initiatives on medical rehabilitation and on the role of the placenta in maternal and child health, as well as efforts to improve our payline and align research funding with evolving institute priorities.

Being new to NIH, I plan to listen and learn from others. In doing so, I expect to gain a better understanding of how NICHD-funded scientists collaborate inside and outside of the institute. I want to help build bridges in pursuit of common research goals. I also would like to increase patient and family engagement in NICHD’s activities, including study design and communications.

You have a lab at NIH. What does your group study?

My laboratory at the National Human Genome Research Institute studies prenatal genomics and fetal therapy. Since 2011, more than 2 million screening tests for fetal chromosome abnormalities have been performed using genomic analysis of cell-free DNA that originates from the placenta and circulates in the blood of pregnant women. This technology has profoundly improved prenatal care because it is more accurate and less invasive than prior screening tests. Also, because genomic analysis is far more sensitive than prior tests, it sometimes detects unexpected disease, such as maternal cancer. My laboratory is particularly interested in the underlying biological mechanisms of unusual or secondary findings that result from whole genome sequencing. One of our goals is to apply DNA sequencing technology to the development of novel biomarkers that identify risks for fetal and placental disease.

In addition, my research group studies gene expression in developing fetuses with trisomy 21, or Down syndrome. For the past 6 years, we have focused on identifying potential drug candidates that help improve fetal brain development following a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. We are analyzing the effects of therapy in cells and animal models. Several people from my laboratory at Tufts have joined me at NIH and we all look forward to establishing productive collaborations with other investigators here.

What advice do you have for early stage researchers?

First, find a mentor who is willing to support your professional development and to put you on the right path to an independent career.

Second, find a program or department that has transparency and a demonstrated track record of protecting time for research.

Third, learn how to communicate your scientific findings orally and in writing. Practice your “elevator speech,” because you never know when you might need it.

Fourth, be persistent and develop a thick skin. Your papers will be rejected and your grant applications won’t get funded, but if you learn from the experience, you will improve.

Fifth, find great collaborators who you can trust and with whom you have good chemistry. No one is an expert on everything; working with others results in unexpected discoveries and frankly, team science is a lot more fun.

Finally, always remember that the data are the data. Don’t ever try to force the data into a hypothesis that initially may have been incorrect. The joy of science truly comes from analyzing the data and realizing that you have found something unexpected, but potentially much more interesting.

What do you like to do in your free time?

I have a wonderful family that includes a husband and two adult sons who still enjoy going on vacation with us. We love to travel; over the past few years, we have concentrated on Central and South America, with trips to Panama, Peru, Chile (including Easter Island) and Argentina. We also like to hike, and with a name like “Bianchi” it wouldn’t surprise many to know that I am an avid cyclist! I also appreciate the visual arts not only for their intrinsic beauty, but also for their ability to enhance the creative process. I am excited to explore the museums in the Washington, D.C., area.