Cooper Navigates Lifelong Journey Toward Health Equity

The contrast was stark. Some kids grew up in spacious homes and attended private schools, while many others lived in shacks without electricity or running water. That was the childhood scene for Dr. Lisa Cooper, director, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity. Growing up in West Africa, she was among the fortunate, but she couldn’t ignore, and remained haunted by, the dire poverty of many of her fellow citizens.

“Those children I saw around me in Liberia were the faces of health disparities,” said Cooper, a professor at Johns Hopkins University schools of medicine, nursing and public health. “I was acutely aware of this, even as a young child, and I always wondered what it would be like if we all had similar opportunities to have a good life.”

Guided by these early memories and inspired by her parents—a surgeon and a university librarian, both involved in civic organizations—Cooper would become a medical doctor and health services researcher, committed to achieving social justice and health equity.

When Cooper arrived in Baltimore 30 years ago for her medical residency, the extreme poverty and neighborhood crime compounded by the drug epidemic were jarring. Many of her patients lacked the opportunity to be healthy. Even today, many African-American patients coming to Johns Hopkins Hospital are poor, with an average life expectancy 20 years lower than the doctors and nurses, most of whom are white and live in affluent neighborhoods.

“Health is shaped a lot by where people live and their life experiences, before they even get into the health care center,” said Cooper, who spoke virtually at the recent WALS Dyer lecture. “I saw communication problems between these patients and the doctors and nurses who were seeing them that often compromised diagnosis and treatment.”

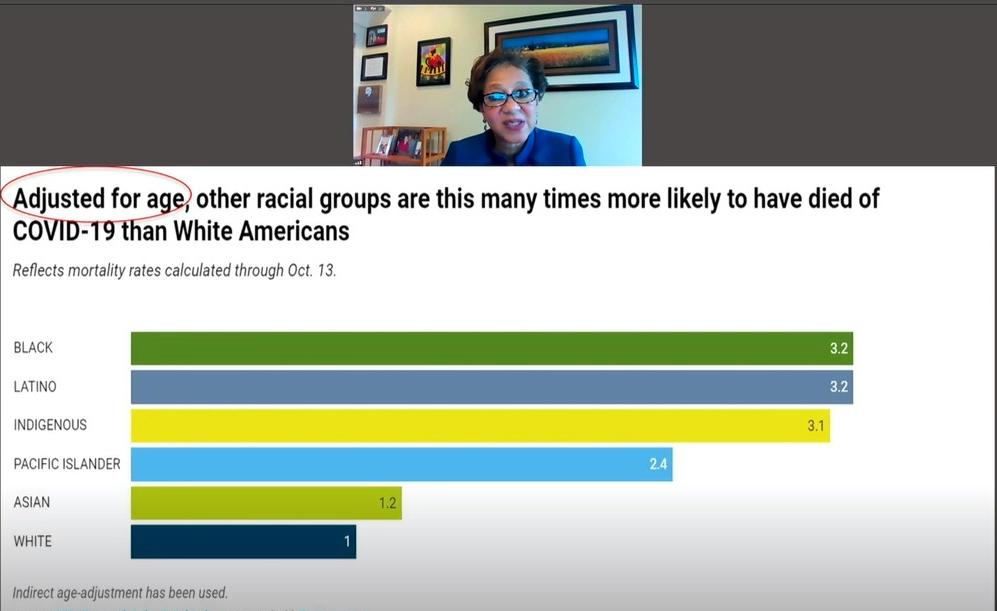

Widespread health disparities affect quality of life and mortality rates for the marginalized, and incur costs that affect all of society. In Baltimore this year, the Covid-19 pandemic has magnified these disparities, noted Cooper, who seeks to change the way health care is delivered to underserved populations.

At the heart of health care outcomes is the relationship among doctors, patients and administrators, from getting a diagnosis to exchanging information to deciding who gets what treatment, said Cooper. Studies she spearheaded found that African-American and Hispanic patients of white doctors participated less in their health decisions and had less trust in their doctors than white patients. Audio recordings of medical visits revealed that doctors dominated the conversation and sounded less empathetic with their Black patients.

“We all, as health professionals, don’t go into medicine thinking we’re going to treat people differently,” Cooper said, “so I think doctors were a little taken aback by [the findings].”

Diving deeper, another study of primary care doctors and their patients in the Baltimore-Washington area using surveys, patient ratings and audiotaped visits found that 70 percent of doctors exhibited implicit bias, favoring Whites over Blacks, and stereotypes that Whites are more medically adherent than Blacks. As the research mounted, Cooper and colleagues contemplated how to reduce these disparities.

She and her team at Hopkins embarked on a three-pronged approach toward sustainable social change on a national and global scale: community engagement—involving health partners, civic organizations and policymakers—research and training. Johns Hopkins University recently launched two courses on health equity research, with thousands already enrolled worldwide, and is developing another on addressing structural racism in health care.

On the research front, Cooper discussed several clinical trials simultaneously examining chronic conditions and delivery of care, results that could help inform changes in health policy. The NHLBI-funded RICH LIFE (Reducing Inequities in Care of Hypertension: Lifestyle Improvement for Everyone) Project has enrolled 1,800 patients from 30 primary care clinics across Maryland and Pennsylvania, with a goal of lowering heart disease risk among minority and low-income populations. Another clinical trial in Baltimore, the NIMHD-funded Five Plus Nuts and Beans for Kidneys, is studying whether low-income African Americans with uncontrolled hypertension could benefit from counseling and incentives to change dietary behaviors.

Efforts are also underway to go global and apply lessons from one setting to another. One such project that JHU launched with Kwame Nkrumah University in Ghana, called ADHINCRA (Addressing Hypertension Care in Africa), is studying ways to improve health self-management among rural and low-income patients. With technology widely available in the country, researchers are exploring whether culturally appropriate text messaging, a Ghanaian-language app and other mobile health technology—along with visits from community-based nurses—would improve health behaviors and outcomes.

Such initiatives have the potential to transform the way health care gets delivered to underserved populations. Ensuring access to care for all, reducing disparities in quality of care, and addressing patients’ social needs are some of the ways to advance health equity, Cooper said.

“It’s really in getting our society to appreciate that inequities in health are about more than individual choices,” she concluded, “[and] that they [inequities] are a lot about these other factors that we as a society have made decisions about how we allocate our resources, and that impact people’s ability to be healthy.”

Cooper continues to steer the course with purpose, not stopping until everyone has an opportunity to attain his or her health potential.

“Together, we are stronger, healthier and better equipped,” she said, “if we can stay on course on this journey with our co-captains and companions, persevering through the turbulence.”