‘The Least of Us’

Quinones Sequel Examines Changing Addiction Crisis

For more than 20 years, a societal epidemic was lurking and burgeoning. It has wreaked havoc on communities across the country, tearing apart families, impoverishing people and killing by the tens of thousands each year.

This national crisis was born out of the misuse and addiction of opioids—prescription pain relievers, heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. From April 2020–2021 in the U.S., more than 75,000 people died from opioid overdoses, a nearly 30 percent increase from the previous year.

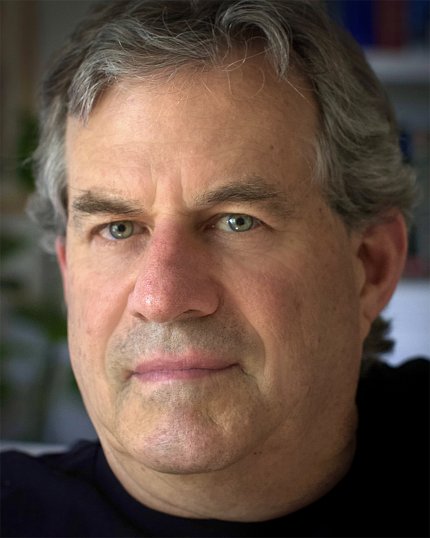

As the crisis was unfolding, author Sam Quinones was living in Mexico and has since interviewed many affected on both sides of the border, from people who are addicted to families who lost loved ones, from imprisoned drug traffickers to prosecutors.

A former Los Angeles Times reporter, Quinones chronicles the rise of black-tar heroin from Mexico in his 2015 book Dreamland. His new book, The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth, delves into the emergence of synthetic drugs in the massive quantities seen today, a topic he discussed during a recent virtual NIDA Director’s Special Lecture.

Roots of a Crisis

It began with the lure of a quick fix for pain and the mistaken belief that prescription opioid painkillers such as oxycodone were non-addictive. Meanwhile, an illegal opioid that yields similar effects was infiltrating the U.S. Heroin, arriving from Latin America, was a game-changer.

“That heroin got here every year cheaper and every year more potent,” said Quinones. “And that is a big reason why we saw the opioid epidemic go from pain pill addiction to heroin addiction.”

As their tolerance to pain pills grew, people found a convenient substitute in heroin. “It awakened the sleeping giant of the Mexican drug trafficking world to the new market that we had created with our pill-prescribing policies.”

Moving Production Inside

Mexican traffickers began shifting from plant-based drugs such as cocaine and marijuana to synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine and fentanyl in the 2000s. These traffickers, descended from farmers and ranchers, had a deep connection to the land but found a new way to do business.

“Meth teaches them that if you can make your own drugs, you don’t need land,” said Quinones. “You don’t care about the seasons or irrigation. You don’t have to employ farmers. You can [do this] indoors.”

And with access to shipping ports, they could import the chemicals and make these drugs year-round.

Cooking Fentanyl: From Powder to Pill

In the early 2000s, as the Mexican government began cracking down on ephedrine, a meth cook in Toluca switched to fentanyl. At first, the infamous Sinaloa cartel was unhappy; they had never heard of it.

“They soon realized he’s created this enormously potent profit center they didn’t even know existed,” Quinones said.

When that fentanyl reached the U.S. in 2005, thousands died before the ring got busted, setting off the first mass fentanyl-related overdose deaths.

By 2014, the fentanyl industry took off. Mexican traffickers began buying and exporting fentanyl, at first in powder form. Early on, U.S. narcotics agents—alarmed by many clusters of overdose deaths—got tipped off by an unusual spike in sales of a common kitchen product: mini blenders. People were trying to mix fentanyl in Magic Bullet blenders, creating a lethal mix.

Photo: Shutterstock/Tim Gray

By 2017, traffickers got sophisticated and began making fentanyl pills, “what we’re seeing now by the millions,” noted Quinones. “Part of the attraction was, by then we were cutting back on doctors prescribing pain pills, and people were still addicted to them.” This synthetic narcotic was filling the ongoing demand.

“Traffickers never really had access to that deep love affair that Americans have with pills,” he said. “Fentanyl offered them that access.”

In 2017, U.S. drug enforcement officials confiscated thousands of fentanyl pills. In 2021, officials had seized more than 9 million pills. “Just staggering,” said Quinones, “and that means probably 10 times more than that were getting through.”

The March of a New Meth

At the same time, the methamphetamine business was changing. Undeterred by crackdowns on ephedrine, a cartel leader started tinkering with a new way to make the psychostimulant, called the P2P method.

Ephedrine meth was cheaper and easier to cook, noted Quinones. But P2P meth could be made in many ways with many different chemicals that are abundant and legal, but also toxic.

P2P meth causes severe symptoms. Hallucinations. Schizophrenia. Paranoia.

“Mentally, the P2P meth is destroying the brain, creating mental illness very quickly,” Quinones said. “It’s a drug where you live in your brain. You isolate.”

There’s so much supply, the price collapses. “The supplies of meth begin to explode, the same as with fentanyl,” he said. “You begin to see it marching across the country. It’s a dangerous situation where we have more of these extraordinarily damaging, deadly, dangerous drugs than we’ve ever seen before.”

‘Anybody Can Be a Kingpin’

The rise of synthetic drugs has stretched the illegal drug trade beyond cartels. “Now, anybody can be a kingpin,” Quinones said.

He tells of a 19-year-old who bought a pill press and a quarter-kilo of fentanyl online. The teen made hundreds of thousands of pills a week, raking in $25,000 a day for a year before he was busted.

“You don’t have to be very smart or savvy to [enter the business] and make a lot of money,” Quinones said. All it takes is a laptop and an internet connection.

Who are ‘the least of us?’

Everyone. “We all have this capacity for addiction. We all can be that addict eating from the trash,” said Quinones. “The least of us lies within us all.”

The deeper he dove into his research, Quinones kept circling back to a misguided cultural ideal driving the crisis.

“One of the reasons we got into the pill problem,” he said, “is we wanted one answer for every single human being for our very complex issues of pain.”

This ideal was set against the backdrop of growing isolation and the withering of community. In Ohio, a swimming pool called Dreamland—the title of his previous book—once held a community together. In Indiana, tool and die shops once dotted Muncie, places important to the town and its energy, where workers proudly toiled daily. But communities have been disintegrating and sites of vibrant public gatherings, like Dreamland, are disappearing.

Quinones tells stories of community repair, of ordinary people reaching out and coming together to make a difference in small ways. Little by little.

“I think the opioid epidemic, and the [Covid] pandemic certainly as well, have taught us that we’re only as strong as the most vulnerable,” he said. “We’re only as strong as the least of us.”