A Bridge of Communication

Ukraine’s Health Minister Visits NIH, Explores Collaboration

Photo: Daniel Soñé

Health care challenges can be daunting for any country even in the best of times; such challenges intensify exponentially during times of war. It’s been nearly a year since Ukraine began battling Russia’s incursion, a war that has devastated Ukraine’s health system. As the war rages on, Ukrainian health officials already have set their sights on recovery and rehabilitation.

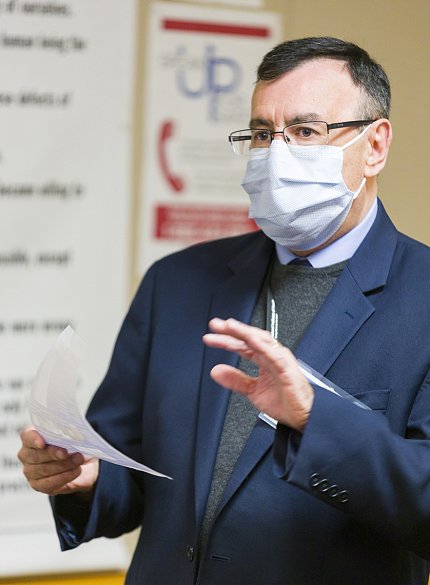

In December, Ukraine’s Minister of Health Dr. Viktor Liashko visited the Clinical Center to discuss his country’s health needs during wartime and beyond, and how deepening ties with NIH might further those efforts.

“While we’re fighting and [engaging] in combat activities on the frontline,” said Liashko through a translator during the Dec. 12 visit, “we’re also as an institution thinking about how to improve and develop our health system and we’re thinking about research and development and all the potential we’ll be able to explore with our partners.”

Photo: Daniel Soñé

Listening to a rundown of NIH research and the inner workings of the Clinical Center—by NIH Deputy Director for Intramural Research Dr. Nina Schor and Clinical Center CEO Dr. James Gilman—Liashko expressed gratitude to NIH and CDC organizers for “creating a bridge of communication between Ukrainian specialists and health care workers and U.S. experts” toward better medical cooperation.

Schor, who hosted the visit, thanked the delegation for making the difficult journey, underscoring NIH is eager to help with their recovery in this challenging period. “We are hoping your visit will be the beginning of a robust collaboration and allow us to learn from one another,” she said.

Photo: Daniel Soñé

NIH currently funds about 20 different research collaborations with Ukraine, mainly between universities, noted Fogarty International Center Deputy Director Dr. Peter Kilmarx, who suggested there are opportunities for additional joint efforts.

Of particular interest, said Liashko, is research on innovative drugs. He also welcomed cooperation between NIH and Ukraine’s National Cancer Institute through joint protocols and research exchange.

Throughout Liashko’s visit, though, attention remained focused on the many health challenges of war, from mental health and trauma to rehabilitation. “We need to think about this right now,” he said, “so we don’t face even more negative effects in the future.”

With that, the delegation moved from the CC’s Medical Board Room to a clinic and a lab to learn more about NIH’s mental health and rehabilitation research.

The Psychological Side: Mental Health

Photo: Daniel Soñé

The war in Ukraine has taken a massive psychological toll on the country’s citizens and soldiers.

“Ever since February [2022], the number of people with mental health issues has exploded and we currently have millions [affected], not thousands,” said Liashko, while visiting a National Institute of Mental Health research unit.

Many are witnessing the effects of war firsthand; many more are exposed to the death and destruction through daily live broadcasts. Psychiatric hospitals are overflowing with patients who have acute mental health conditions, he said. Drug use—from sedatives to illicit drugs—is soaring. Soldiers are returning with withdrawal symptoms and serious mental health issues, including suicidal tendencies, and need urgent help.

Preliminary estimates show some 15 million people—nearly a third of Ukraine’s population—will have psychological trauma from the war. Liashko estimated at least 20% will need medication and other treatment beyond basic support.

“That’s why during this active phase of war,” he said, “we are thinking about mental health issues and research developments because we understand it will take a lot of effort, time and resources to deal with it on different levels.”

Dr. Carlos Zarate, chief of NIMH’s Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch, addressed the delegation about depression and suicide prevention research. He noted that many patients don’t respond to standard antidepressants which, when they do work, can take a long time to provide relief.

“Our focus is on developing therapies for treatment-resistant depression that work in hours or days, instead of weeks or months,” said Zarate. His lab has been studying ketamine, an anesthetic that works efficiently and fast but has serious drawbacks.

Photo: Daniel Soñé

Recently, Zarate’s lab developed a compound from a metabolite of ketamine that does not have the anesthetic’s side effects or misuse potential. It’s headed for clinical trials this year at the CC’s NIMH research unit.

Liashko expressed interest in the research and in collaborating with NIH on additional mental health disorders, notably post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Zarate looks forward to collaborating. By investing in mental health resources, he said, “you can address [problems] early and minimize impact for years to come.”

The Physical Side: Rehabilitation

Photo: Daniel Soñé

Ukrainians are incurring serious injuries during the war, yet rehabilitation medicine is virtually nonexistent in Ukraine, said Liashko.

In the U.S., rehabilitation medicine accelerated in the decades after World War II, treating such common war injuries as burns, limb loss, and spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries (TBI). To study brain injuries incurred on the battlefield, NIH partnered with the U.S. military more than a decade ago to create the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (CNRM), the largest TBI research collaboration in the world.

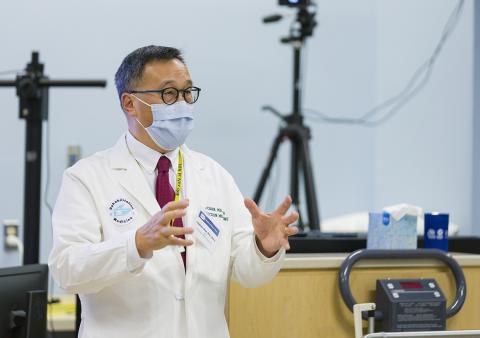

Dr. Leighton Chan, chief of the CC’s Rehabilitation Medicine Department and co-director of CNRM, discussed two protocols from the collaboration. Early results from one study, he said, suggest that “prolonged exposure to heavy weapon blasts transiently raises the level of injury biomarkers and causes temporary neuropsychiatric changes.”

Photo: Daniel Soñé

Chan also cited a concussion study showing that aerobic training can decrease symptoms of TBI perhaps by resetting vascular reactivity in the brain.

“Many are suffering these types of injuries from all the bombing and shelling,” said Liashko, who is eager to collaborate on similar protocols.

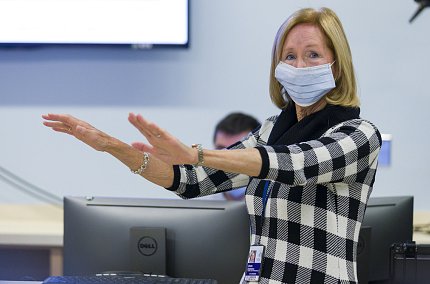

Dr. Diane Damiano, chief of the CC’s neurorehabilitation and biomechanics research section, then demonstrated how their lab assesses motion, muscle strength, balance and brain function during movement as a basis for establishing a patient’s rehab needs or evaluating recovery over time.

Photo: Daniel Soñé

“People with TBI look pretty good from the outside, but when you challenge them—such as a mental test while walking—we can start to see their deficits more clearly,” she said. She also emphasized the need for intensive motor training to help patients recover mentally as well as physically.

Pledging collaboration, Chan said, “This is the beginning of a conversation.”

Later in the day, the delegation met with Dr. Lawrence Tabak, performing the duties of NIH director, and senior leaders from other HHS agencies.