Lessons in Astronomy

Valdez Authors Second Children’s Book

Dr. Patricia Valdez enjoys discovering and sharing stories about women scientists. Her first children’s book is a real-life dragon tale; her second book is something out of this world.

Valdez has worked at NIH for 14 years, first as an immunologist and, for the past decade, helping to ensure integrity in research grants. By day, Valdez is NIH’s chief extramural research integrity officer. She also has found her calling writing children’s books.

Her latest book, How to Hear the Universe, takes a topic in astrophysics and turns it into a vibrant, relatable story that people of any age will enjoy. The story begins with Albert Einstein hypothesizing about the existence of gravitational waves. Valdez illustrates the concept of these waves, these ripples in space-time, by describing frogs jumping across lily pads.

These ripples were undetectable in Einstein’s lifetime. But recent technology has made their detection possible and, nine years ago, scientists first heard them. The person who stepped up to the podium in 2016 to announce the breakthrough was Dr. Gabriela González, the heroine of Valdez’s book.

“I’d never seen a Hispanic or Latina scientist on that big of a stage announcing an international scientific discovery,” said Valdez. “Her energy was infectious.”

Valdez, who is of Mexican descent, added, “I’m always looking for women scientist role models. I didn’t have that growing up.”

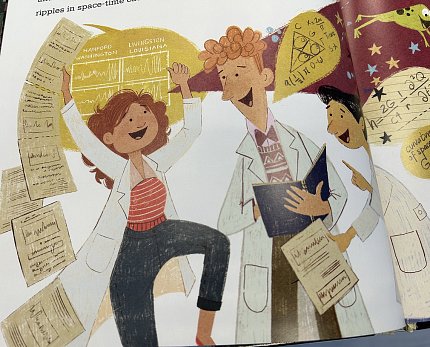

Photo: Sara Palacios / Knopf

Valdez’s book introduces González, who was born 50 years after Einstein published his 1915 Theory of Relativity. As a young girl growing up in Argentina, González loved to gaze up at the stars and wonder about the unknowns of the universe. She studied physics, moved to the U.S. after college to pursue her doctorate and became the first female full professor in physics at Louisiana State University.

Across the state, scientists were building one of two giant structures to study gravitational waves: one in Livingston, La., the other 2,000 miles away in Hanford, Wash. González joined the research team on the Louisiana side of this new facility called LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory).

In 2015, LIGO scientists discovered the ripples by accident. The team was conducting tests one day and left the machines running overnight. At the crack of dawn, the facility in Louisiana pinged and, milliseconds later, the Washington facility chirped. Scientists in Germany received the pings and contacted their counterparts in the U.S.

LIGO scientists checked and re-checked and confirmed these were indeed ripples in space-time that stemmed from two black holes colliding a very long time ago.

“The energy released caused space-time to ripple, just like the collision of the frog and lily pad causes ripples,” Valdez wrote in the book. “Those ripples moved toward Earth over time and, more than a billion years later, they passed through LIGO.”

Photo: Sara Palacios / Knopf

Before Valdez could publish the book, she had to check the science. She admitted that writing this book was a bit intimidating. Unlike her previous book Joan Procter: Dragon Doctor—about a woman who cared for Komodo dragons at the London Zoo about a century ago—her new book featured a living scientist.

“I’m an immunologist,” Valdez said. “What if I misunderstood Einstein’s theory of relativity?!”

She emailed the manuscript to González, whom she hadn’t yet met and, to her delight, González responded that she loved the book. González even supplied some of her own physics equations from LIGO experiments, which illustrator Sara Palacios incorporated into the book’s colorful artwork.

Valdez enjoys sharing How to Hear the Universe with children and seeing them light up at images of nebulas and space. When visiting elementary schools, she emphasizes the importance of science communication.

“If you can’t communicate the things you’ve discovered, nobody is going to know they happened,” she tells the kids. She also says, “You don’t have to be a writer or a scientist. You can be both! Follow your passions. Don’t limit yourself.”

Valdez sought to convey in this book the long, rewarding journey of scientific discovery, which starts with a hypothesis followed by lots of rigorous testing.

“I wanted to show readers it was not just a lone person working in the lab,” Valdez said. “LIGO is a collaborative effort that involves thousands of scientists from around the world.”

When conducting an experiment, she said, “the most exciting part is when you finally understand something that nobody else in the world understands at that point. For me, that excitement, that feeling of discovery, is the best part of being a scientist.”