Scientists One, Superbug Zero

Personal Quest Resurrects Phage Therapy in Infection Fight

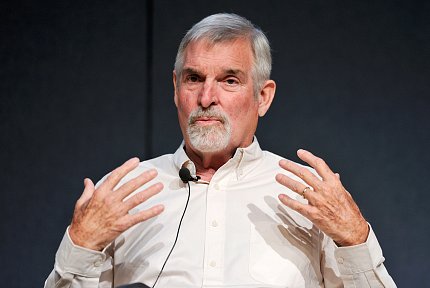

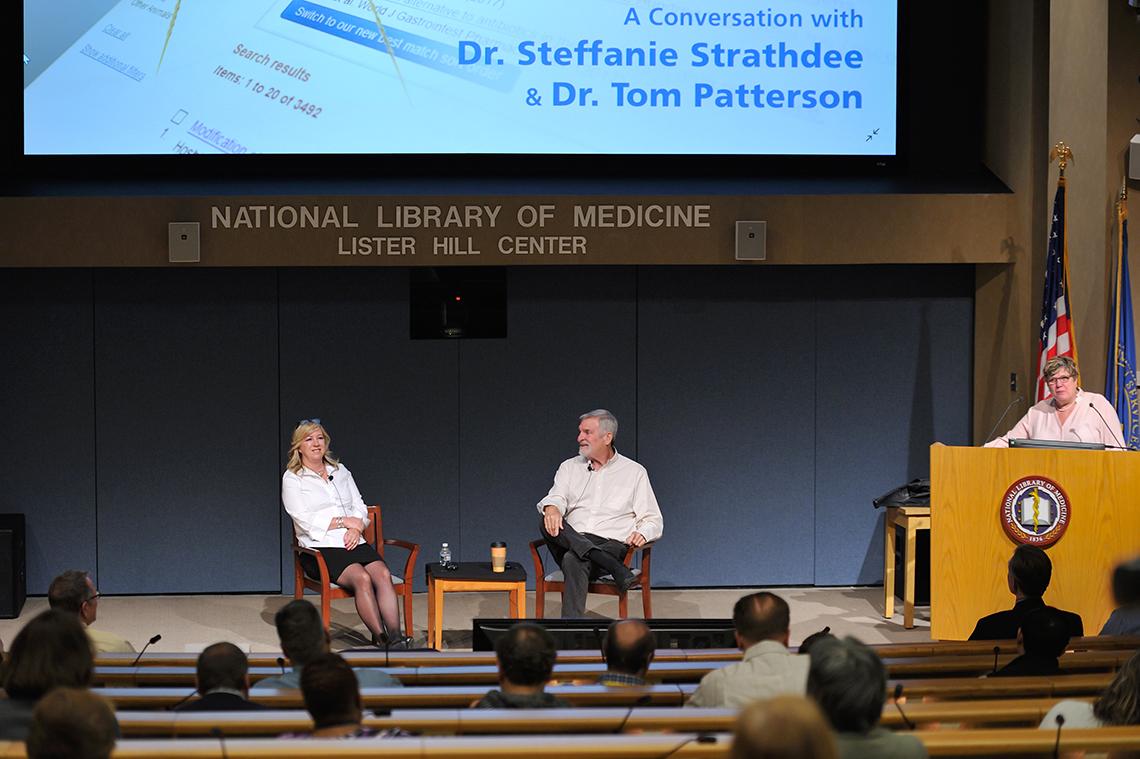

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

At one life-or-death moment, Dr. Tom Patterson was a snake.

In November 2015, he and wife Dr. Steffanie Strathdee were merely two scientists on holiday. The couple had been vacationing on a cruise in Egypt. After a day of pyramid probing and an evening meal aboard ship, Patterson fell ill. Food poisoning, he surmised. A dose of routine antibiotics, they thought, and he’d be shipshape by morning. Only he wasn’t. Sicker and sicker he grew, as symptom after symptom occurred. Vomiting, abdominal pain, then a back ache. He was diagnosed with gallstone pancreatitis, but that was the least of their problems. That he had some kind of serious infection eventually became clear, but precisely what was wrong—and how to fix it—remained a mystery that would confound physicians and scientists, and inevitably force Patterson to make medical history.

At Lister Hill Auditorium on Mar. 1 to discuss their harrowing adventure, the erstwhile tourists—she, associate dean of global health sciences at the University of California, San Diego, and he, psychiatry professor in residence there, and both current NIH grantees—are on a mission now, some 3 years after facing down a deadly superbug.

Now completely recovered, Patterson and Strathdee feel compelled to tell how they won—with considerable help from the global village of scientists via social media and PubMed, the online collection of 29 million biomedical literature citations.

“We decided that we needed to tell our story because total strangers stepped up to help us,” said Strathdee, “and we want to pay it forward.”

Wrong Valley

Strathdee and Patterson were supposed to be exploring the Valley of the Kings, the burial grounds of pharaohs, along the Nile in Luxor. Instead, he was skirting the “valley of the shadow of death,” and she was scrambling for answers, courtesy of something no one could seem to pinpoint.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

Days turned into weeks; weeks became months. Doctors had exhausted all antibiotic treatment options and Patterson was dying, comatose with organs failing. At hospital bedside, Strathdee knew time was short. He was too weak to take much more. With his life in the balance, she wondered, could she even get through to him for the ultimate decision?

“Honey I know you’re trying very hard to fight this thing,” she said to him. “The doctors don’t have any antibiotics left and I need to know if you want to live. If you want to let go, I’ll understand, but I want to grow old with you. I love you very much. So if you want to live, please squeeze my hand and I will leave no stone unturned.”

Patterson heard her through his addled mind but understood. However, amid all his medical issues, he was also dealing with a practical problem, one of evolution and anatomy.

“I was actually a snake,” he recalled, describing one of several particularly vivid hallucinations he endured throughout his health crisis. “I mean in my mind, what you need to understand is this isn’t like, ‘I kind of remember being a snake.’ In my memory there is this place where I was a snake. So when Steff asked me to squeeze her hand if I wanted to live, it was a challenge because snakes don’t have hands. I had to figure out how to wrap my body around her hand and squeeze, and I didn’t know my own strength as a snake, so I squeezed too hard.”

By the Numbers

Six bacterial pathogens make up the so-called “ESKAPE” superbugs that can resist most commonly used antibiotics. Each letter in the acronym stands for a deadly organism; Patterson’s foe proved to be a strain of the “A”—Acinetobacter baumannii. The hardy bacteria, known to thrive in hospitals, can survive multiple temperatures, conditions and environments.

It had taken two medevacs via Lear jets and 7 ambulances over 3 continents and several countries to get Patterson back home to San Diego. Still, familiar surroundings hadn’t presented a cure.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

Countless champions—and myriad fortuitous circumstances—factored into Strathdee’s quest to save her husband. That’s partially why the couple documented their story in their new book, The Perfect Predator, and why they’re heralding the international scientific community at large.

“If it wasn’t for PubMed, our university hospital at UC San Diego and a global village of researchers from around the world—like Dr. Chip Schooley and other renowned NIH-funded researchers—he would be dead and I would be holding an urn instead of his hand.”

Strathdee had rejoiced when she felt Patterson’s clasp, which meant he wanted to continue the battle. It also meant she had to deliver on what seemed an impossibly complex and circuitous search for something to arrest the infection that was by then throughout Patterson’s body.

About a century and 3 decades—respectively, that’s the period since Western medicine has seriously considered using bacteriophage (“phage” for short) to eat infections like Patterson’s, and the time that has elapsed since Strathdee was a microbiology undergrad familiar with this field of science.

Search Every Sewer?

The rise and success of antibiotics relegated phage therapy research to the back burners of science, particularly in the U.S.

Phages are notoriously finicky and ESKAPE infections are just as fussy. For this last-ditch therapy to work, bacteria eater would have to be precisely matched to superbug.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

Also, speaking of ditches, where does one look for organisms that feast on bacteria? Yep, the sewer is home to both culprit and cure. Fortunately for Patterson, several research labs studying the pathogens have assembled libraries of sample phages. The phage would also have to be purified before being infused to Patterson.

“So now it was up to me,” Strathdee said. “How am I going to find phages that are going to match Tom’s organism? And the reading I did showed that there’s 10 to the power of 31 phages on the planet—that’s 10 million trillion trillion phages. I was so overwhelmed by this. I thought it’s worse than a needle in a haystack.”

She did what anyone else might do in a desperate medical dilemma: She Googled.

She also enlisted all her scientist contacts in the phage hunt. She posted pleas to social media, complete with images of Patterson bedridden in a coma. She called in every favor and was gratified by the response of folks who didn’t know her or her husband. Phage experts from around the globe took up the challenge. The Navy Medical Research Center in Frederick, Md., also joined the hunt along with phage researchers from Texas A&M University.

“I realized that my husband was becoming somewhat of a poster child for this dystopian future of the superbug crisis,” Strathdee quipped.

In March 2016, Patterson became the first person in the U.S. to receive intravenous phage therapy for a systemic multidrug-resistant infection. He awoke from the coma 3 days later. In all, he survived 7 cases of septic shock, untold organ system shutdowns and dozens of hallucinations over 9 months. He was lucky, but so many more people are not, Strathdee pointed out.

Opportunities, Moving Forward

In addition to an enormous sense of gratitude toward their large network of colleagues and the wide range of information and other resources made available to them in record time, the couple has a public health message.

“1.5 million people are dying every year globally due to superbugs,” she noted, “and that’s estimated to grow to 10 million a year, or 1 person every 3 seconds by the year 2050—unless urgent action is taken. And a lot of our governments are actually doing the wrong thing and promoting policies that are misusing and overusing antibiotics, especially in livestock and agriculture.”

The couple’s ordeal also presented opportunities for future scientific research, particularly in the areas of global health, alternative therapies and precision medicine. In fact, Strathdee and one of the scientists who helped battle the bacteria, Schooley, launched and now codirect a Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics at UCSD, the first dedicated phage therapy center in North America. They’re hoping to launch two clinical trials in 2019.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“Scientists are often very removed from the public. We see ourselves as NIH-funded researchers who are supported with taxpayer dollars,” Strathdee concluded. “We feel it’s our obligation to share our story with the public so that people can see that scientists are people…We want to make this kind of research accessible…Through our book, we hope that we’ll be able to take this story globally and make a difference in the global superbug crisis.”