‘Databrary’ Promotes Sharing, Reuse of Video for Researchers

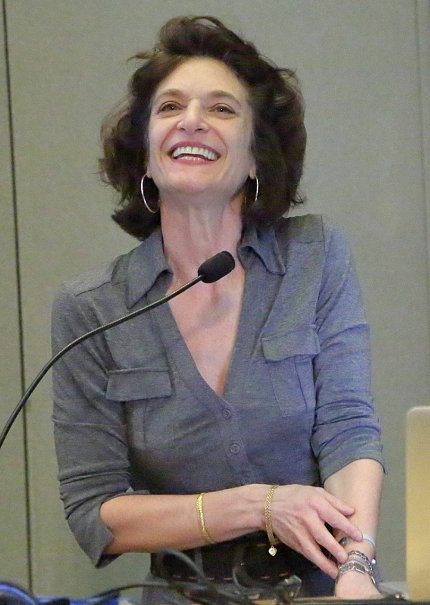

Photo: Ernie Branson

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a video is worth a thousand pictures.” That’s how important video is to developmental research, said Dr. Karen Adolph, professor of psychology and neural science at New York University.

Video gives researchers the opportunity to watch what happens in the blink of an eye—and the ability to repeat that instant, over and over again if need be, she said at a recent Behavioral and Social Sciences Lecture in Natcher Bldg.

Researchers have been using video and film to record infant behavior since Arnold Gesell and Myrtle McGraw pioneered the practice in the 1920s and 1930s. Video allows researchers to gain “new insights into the causes and consequences of learning and development,” Adolph said. “It’s the cheapest, easiest and most effective way to record what people do.”

Video plays an important role in her lab, where she studies how infants, children and adults interact with their surroundings. The lab features specially designed playground equipment where infants can walk across bridges, use handrails to steady themselves and climb over gaps, for example. Recently, her lab helped develop head-mounted eye-trackers for mobile infants and children. These trackers make it possible to record what babies see as they crawl, walk and climb and how a baby’s view of the world differs from the view of their mothers.

“Video allows us to see the extraordinary in behaviors that otherwise seem ordinary and to see the ordinary in what may seem at first glance to be extraordinary,” she said. “Behavior is always rich, complex and organized. And it’s often surprising.”

Researchers, however, rarely share their research videos. Once an investigator completes a study and publishes a journal article, the video just sits on a computer or hard drive. No one ever watches it again.

That’s why Adolph helped to build Databrary, a digital library for sharing and reusing videos. Currently, 350 scientists from 144 research institutions all over the world have uploaded more than 3,500 hours of video to the library. Most of the data is already coded for behavioral observations using a free, open source program called Datavyu that Adolph also helped to develop or using similar academic or commercial video coding tools. Sharing video excerpts for educational purposes, she noted, is another benefit of Databrary.

Photo: Ernie Branson

To protect research participants’ privacy, only authorized investigators are allowed access to Databrary. Authorized investigators must sign an agreement, show that they have training in human research ethics and work at a facility with an institutional review board. To share video footage with the Databrary community, researchers must get participants’ permission to do so.

Asking for consent is easy, Adolph said. Databrary provides template language that researchers can adapt for their own use and videos that show researchers how to request permission. “We recommend that researchers ask for permission to share videos after the study is over,” said Adolph, “so it’s really clear to the participant what exactly happened and what behaviors were recorded.”

Most parents, she said, are happy to let researchers share videos with other researchers because “most developmental research concerns the kinds of behavior that parents are posting on YouTube and Facebook already.” Most parents of children with disabilities are also eager to share because they hope to speed progress and understanding about developmental disabilities.

Adolph frequently reuses videos for her own research. For example, she and her colleagues collected videos of infants during free play to discover the quantity of locomotion infants spontaneously produce. Babies were recorded in a lab playroom.

Based on these data, she concluded that toddlers, on average, take 14,000 steps and fall 100 times per day. She submitted these findings to a high-impact research journal. The paper was initially rejected because a peer reviewer questioned whether babies moved so much because they were in a novel environment. So Adolph reused videos collected for a completely different study of infants playing in their own homes. She counted steps and falls and found no differences between how much babies move in the familiar environments of their homes and the novel environment of the lab. She resubmitted the paper and it was published.

“Infants fall just as much in their homes as they do in the lab,” Adolph said. “By reusing videos collected for a completely different purpose, we were able to answer a new question from old data.”

No researcher has enough expertise to answer important developmental questions alone, Adolph noted. As a motor development expert, she can’t write scientific articles about how motor development affects social interaction, for instance, without collaborators.

However, if she has access to videos coded by language or social development experts, “I think I’m smart enough to relate how those ideas [apply to] motor development—where I have expertise,” she said. “Imagine how much we will discover when it is easy for researchers across the globe to share videos with one another.

“All behavior is good behavior,” Adolph concluded. Even though it may not be interesting to one researcher, it is likely to interest another.

Databrary is funded by NICHD and the National Science Foundation. Visit https://databrary.org/ for more information.