‘Harassment Does Not Work Here,’ New Policy States

Just days before NIH rolled out a comprehensive effort to define and address workplace harassment in all its forms, representatives of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) presented findings and recommendations of a NASEM report on sexual harassment of women in science to a large and keenly interested Lipsett Amphitheater audience.

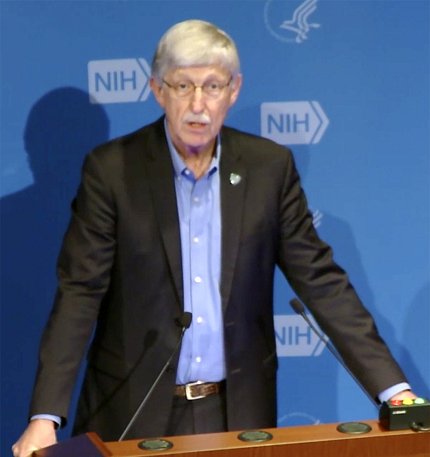

Sitting in the front row were NIH director Dr. Francis Collins, who opened the 2-hour-plus session, and NIH principal deputy director Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who chairs NIH’s intramural anti-harassment steering committee, and acting chief of staff Dr. Carrie Wolinetz.

“This is an incredibly important topic and lots of things are happening right now,” said Collins. “This has been on our minds for a long time. Sexual harassment is simply unacceptable.”

Calling the NASEM report “quite thorough” and its conclusions “quite sobering,” Collins added that “an environment often perceived as hostile is not only utterly inappropriate but also has serious consequences,” including some women actually quitting science at a time when it is already hard to recruit them.

“These are difficult topics to discuss,” Collins allowed, “and that may have inhibited us in the past, but we’re done with that…Harassment does not work here. We don’t believe this is something we can tolerate.”

The session, part of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research Grand Rounds Lecture Series, included presentations by Dr. Frazier Benya, senior program officer for NASEM’s committee on women in science, engineering and medicine, and Tom Rudin, director for NASEM’s board on higher education and workforce.

“Like cancer, sexual harassment affects us all,” said CCR director Dr. Tom Misteli, in prepared remarks (he was home sick, “a victim of biology”) “and we need to resolve it together…We need to change the culture so that complete absence [of sexual harassment] should be the norm.”

Rudin, who 38 years ago was an intern at NIH, said his committee has been working for 20 years on the challenges facing women in STEM careers. “We always talked about sexual harassment, but kind of put it aside.”

Two years ago, NASEM looked at it more explicitly; he and Benya are now touring the U.S., mainly college campuses, sharing study results.

“We always ask, ‘Who’s trying hard to solve the problem,’” said Rudin, “and we point to [NIH]. You’re taking this extremely seriously…Sexual harassment can be reduced. It can be stopped, and we know how to do it. But it needs will, incentives and encouragement.”

Benya said that in fall 2016, NASEM set out to review the prevalence of sexual harassment in STEM fields, assess its impacts and define policies found most successful in addressing and preventing it.

Four broad themes emerged:

- Gender harassment is a type of sexual harassment.

- The cumulative effect is significantly damaging to science.

- The legal system alone is not adequate to address the issue.

- System-wide changes are needed.

“Institutions can do it,” she declared.

She outlined three kinds of sexual harassment defined in the NASEM report.

- Sexual coercion, or “Sleep with me or you’re fired.” This is the rarest form.

- Unwanted sexual attention, which can be as extreme as assault.

- Gender harassment. “This is the most common form,” Benya said. “It can include verbal and visible conduct…It demeans, denigrates and humiliates people, in gender-based ways.”

Thirty years of research have demonstrated that “sexual harassment can be direct or ambient—it’s harmful in both cases,” said Benya. “It takes a toll on victims.

“Fifty percent of women in science experience gender harassment,” said Benya. “Twenty to 50 percent of students feel it from faculty and staff.”

Gender harassment is significantly higher in medical school settings, Benya reported, nearly triple the frequency found in the sciences and almost double the frequency found in engineering.

“Women of color experience more harassment than white men, white women and men of color,” Benya noted, “and it often includes racial harassment.”

The impact of harassment on victims’ health includes depression, stress, anxiety, headaches, sleep problems and other ailments. “One in 5 sexually harassed women meet the criteria for depression,” Benya said.

Sexual harassment derails women’s work lives, she explained. Many disengage from work, or leave their profession. “All of this, to escape an abusive situation.”

One need not be directly targeted to feel the effects of sexual harassment; there is a circle of influence, or bystander effect, that spreads, Benya said.

“Even the men leave—they don’t stick around to watch their valued colleagues suffer.”

The cumulative effect is significant damage to research integrity and costly loss of talent in academic science and medicine, said Benya. NASEM’s committee on women in science believes sexual harassment should be considered on par with research misconduct.

Legal strictures on sexual harassment are necessary, but not sufficient, said Benya. “They are often symbolic only” and crafted so that institutions avoid liability.

“Targets do worry about retaliation,” she emphasized. “Many just want the behavior to end. They don’t want to go through the court system…Actually, the least common response is to formally report the sexual harassment.

“We need to move away from a culture of compliance to one of respect,” said Benya. “We need to stop relying exclusively on formal reports.”

NASEM found that two factors are most associated with sexual harassment: male-dominated environments and leadership and a climate that tolerates sexual harassment.

“Climate is the greatest predictor of sexual harassment,” said Benya. What makes a permissive climate? First, the risk to victims of reporting. Second, a lack of sanctions. Third, a fear that you won’t be taken seriously.

She concluded with NASEM’s 6 key recommendations for academia:

- Create diverse, inclusive and respectful environments.

- Diffuse hierarchical and dependent relationships between trainees and faculty.

- Provide support for targets that doesn’t depend on filing a formal report.

- Improve transparency and accountability. “We need clear policies and disciplinary steps, and annual reports that include investigative results—what action was taken?” said Benya, who noted that the NASEM committee also called for climate surveys (NIH is doing that, starting in January).

- Strive for strong and diverse leadership; make preventing sexual harassment an explicit goal.

- Make the entire academic community responsible for reducing and preventing sexual harassment.

The NASEM study committee also had recommendations for professional societies, policy makers and federal agencies.

The second hour of the program featured a panel discussion among members of NIH’s various women scientist advisory committees, OD offices dealing with human relations issues, plus a Q&A session with the audience. Key takeaways included:

- Dr. Kelly Ten Hagen of NIDCR called for 4 specific elements in an NIH intramural anti-harassment plan: clear definition of what constitutes “consensual relationship,” centralized reporting and investigating to avoid conflict of interest, an anonymous hotline for information and reporting (which has been adopted by NIH, according to Jessica Hawkins, supervisor of the NIH Civil Program) and involving the Office of Intramural Training and Education in protecting “our most vulnerable population—young trainees…A lot of behavior is not sexual,” Ten Hagen said, “but is nonetheless hostile and harmful.”

- Employees will have to take annual POSH (prevention of sexual harassment) training, said Hawkins. “You can’t opt out of this issue—it involves everyone.”Over the last year, the Civil Program has seen significantly increased reporting of workplace concerns, including harassment.

- Multiple mentors are crucial in a field where so much power can be concentrated in a single individual, argued several people.

- Men need to be made to feel comfortable about addressing these issues.

- Harassment can feel like “death by a thousand cuts”—there is often not a single, obvious “reportable” offense.

- Elite institutions can unwittingly accept abusive behavior from a famous or unusually productive scientist that wouldn’t ordinarily be tolerated from someone less professionally esteemed.

- Poor anti-sexual harassment training is worse than no training at all, concluded NASEM’s Rudin.

NIH Anti-Harassment Program

NIH has launched an Anti-Harassment Program for NIH staff that includes two new policies, a new educational video, a new web form and hotline for reporting allegations of harassment, and information about the upcoming workplace climate and harassment survey that will be administered in early 2019.

Learn more at https://hr.nih.gov/working-nih/civil.