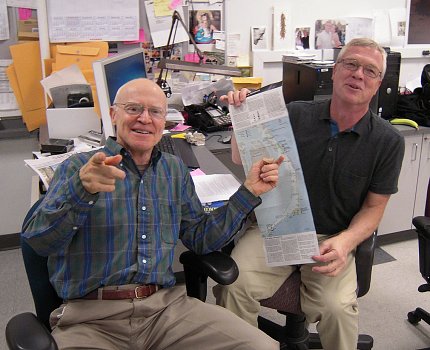

Bransons Reunite

Second Brother’s Retirement Ends Era at NIH

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

For the past 30 years at NIH, if you needed photos taken by medical arts, chances are you got one of The Brothers—Bill or Ernie Branson.

Bill, the more extroverted of the two, retired last year after 33 years on campus and is now NIH photographer emeritus, a position created within the Office of NIH History. Ernie, the quieter brother, ended a 40-plus-year government career in September. He now joins Bill as photographer emeritus; the two have an office in Bldg. 60 where they help archive NIH’s vast store of images—many of which they took.

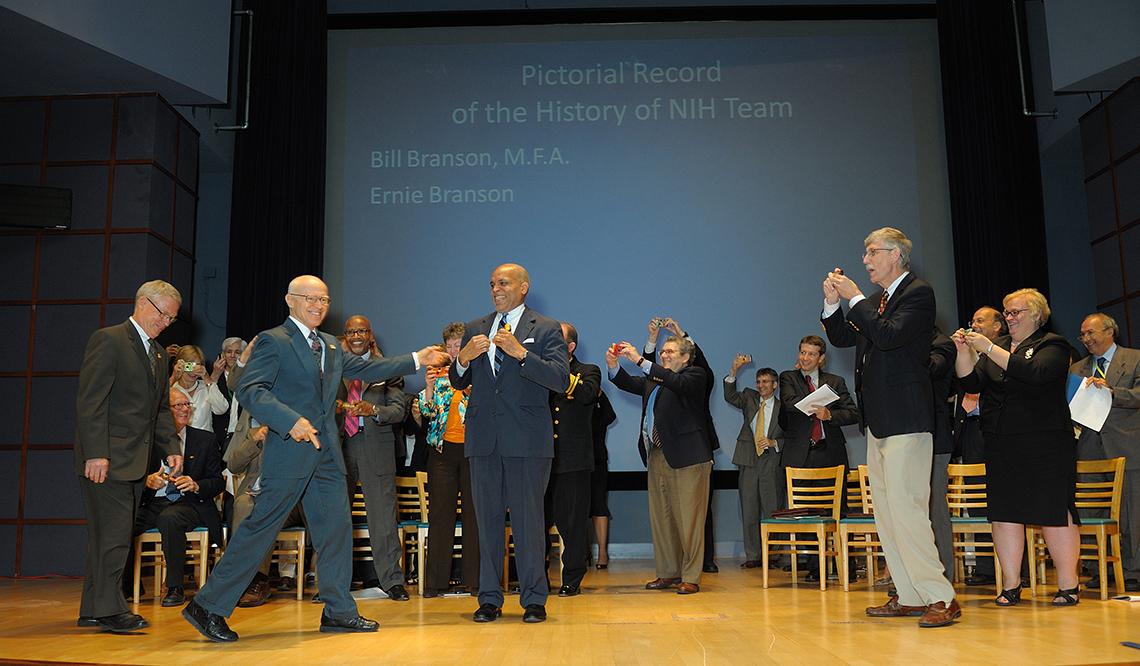

“Ernie is a stand-out,” said NIH director Dr. Francis Collins. “I always knew things were under control when I saw that he or Bill were on the scene. Photographs are such an important part of telling the NIH story and Ernie played a key role in helping us do that. In fact, Ernie and Bill received an NIH Director’s Award in 2010, to recognize their exceptional service. Just for fun, as they were on stage to receive the award, all of the institute directors jumped up and took pictures of them. I’m glad to know Ernie is staying on with Bill as a volunteer. That way, we won’t lose his deep knowledge of NIH or his wonderful sense of humor.”

Adds Dr. Michael Gottesman, NIH deputy director for intramural research: “Ernie has been, ironically, the most invisible visible member of the NIH community, someone responsible for so many of our family snapshots but never appearing in the photo album because he was the one taking the pictures. This is why I am thrilled to announce that Ernie will be given the title of NIH photographer emeritus, where he will join his brother Bill in the Office of NIH History and can remain a visible presence on the NIH campus for many years to come.”

“The team is back together! It’s gonna be great,” said Ernie, as retirement neared. “When we’re together, it’s just right.”

Known for their quick, non-invasive style and technical skill, The Brothers were also renowned as easy—and downright fun—to work with. Many NIH’ers hired them during off-hours to photograph their weddings and bar/bat mitzvahs.

Though at 66, Ernie is 5 years younger than his brother, he actually began working in medical arts at NIH 4 years earlier than Bill, who arrived in 1984.

The boys grew up in Bethesda, not far from NIH, and their dad worked for Pepco for 45 years. When it came time for college, Ernie had to pay his own way.

In order to afford tuition at Montgomery College, where he studied civil engineering, Ernie got a job as a stay-in-school at NIH. The year was 1972.

Photo: Roger Glass

Asked what he’d like to do here, Ernie, who had been a gas station attendant and lawn cutter as a teen, admitted he didn’t know. “I just wanted to work and get paid.”

He was put to work at NCI, cleaning cages for rodents and rabbits. It was indoor work with no hot radiators or searing sun and Ernie loved it. “It was the best job I had in my life.”

Ironically, it was his mowing work that had introduced him to NIH. “One of my customers was Mr. Black, who worked at the blind stand in Bldg. 10. He put me to work cleaning the store refrigerator and let me eat all the candy I wanted. I loved it.”

As a cage washer, Ernie reported to a Roosevelt Ingram on the 8B level of Bldg. 10. Ernie was good at math, and in his free time tutored Ingram, who was trying to better his employment. Ingram introduced Ernie to a client, Cecil Lee, who ran an EM microscope and kept hamsters whose cages needed cleaning. Lee also had a darkroom.

“[Lee] liked me and we hit it off and had fun,” Ernie recalls. “He asked if I had a camera.”

Bill, when in Vietnam, had sent Ernie one. Lee showed Ernie how to load it, use an enlarger and make his way around the sinks and chemicals of the darkroom.

“The seed was planted there,” said Ernie.

Lee not only taught Ernie the ropes of photography, but also introduced him to a second mentor—Ralph Isenburg, a legendary, one-eyed NIH photographer whose career here spanned 50 years; his darkroom on the B2 level of Bldg. 10, once a morgue, still bears his name today.

But after only 4 months at NIH, Ernie got drafted.

“I wasn’t in the mood to go,” recalls Ernie. “I had a girlfriend, I was having fun, all my buddies were here, we were seeing Jimi Hendrix at Merriweather Post Pavilion…”

But his dad had been a pilot in World War II, and Bill was by then a Vietnam vet. Ernie realized, “Ya gotta go, dude.”

Fortunately, Ernie’s 2-year Army hitch went only as far toward Southeast Asia as Hawaii, where he learned to aim howitzers as a fire direction coordinator. And at the bases where he trained, he also took photography classes, for future employability.

Photo: Michael Spencer

By the time he re-enrolled at MC in fall 1974, the school offered a photography major. Ernie graduated in 1976 with an associate’s degree in photography.

Tuition money was still an issue, so to complete an undergraduate degree, Ernie enrolled at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. The reason was simple: “I could afford it—you could get Illinois residency in 3 months.

“They took all my credits [from MC] except slide rule class. By then those were antiquated—everyone had a calculator. SIU had a wonderful photography department, offering both professional and fine art training; most schools only offer fine art,” said Ernie. He went pro and in 2 years had a B.A.

During that time, he had persuaded Bill to join him at SIU; the two shared a 2-bedroom trailer that Bill had bought from a migrant farm worker. “That was wonderful living,” Ernie recalls. He slept behind a sofa in the living room; they had converted the second bedroom to a darkroom.

Ernie picked up additional camera experience working for the school paper, the Daily Egyptian. Both brothers also had internships that ripened into paying jobs at the Southern Illinoisan, a daily in Carbondale. Interestingly, Ernie had turned down an internship at the Carter White House—“I would have lost a semester and I didn’t like grip-and-grins.”

His first paid newspaper assignment was a Charlie Daniels Band concert at the DuQuoin State Fairgrounds. “I stood right in front of a speaker to get some stage shots—that’s probably why I’m deaf in one ear,” he laughs. “I thought, ‘Man, I like this!’ It was real exciting work.”

But small-town newspapers don’t pay much and Ernie was restless. “I thought, ‘I’m so tired of being poor—I’ve got to get to work.’”

While Bill stayed on in Carbondale for his M.F.A. in photography, Ernie came home to Bethesda, working a series of odd jobs and living at home.

While seeking a government job at NIH, Ernie’s old friendship with Cecil Lee paid off once more.

“I met a Mr. Singletary [in medical arts],” Ernie recalls, “and he wanted to hire me.” Lee had introduced Ernie to Singletary years earlier and Singletary remembered him.

In June 1980, Ernie joined the photography section of medical arts, but not to take pictures. He was given darkroom work and back-of-the-house jobs preparing slides for scientific presentations. The dues-paying lasted 4 years.

Frustrated by the lack of camera work, Ernie took a job as an ophthalmic photographer for NEI that lasted 4 more years.

“It was a job,” Ernie recalls.

Then came what Ernie calls “the hardest thing I ever did in my life.” Both he and Bill were finalists for a single job as NIH photographer.

“By then I had three kids, and Bill was a bachelor who didn’t have a job, so I took my name out of the hat for Bill. Back to the ophthalmic world I went. But Bill did such a good job during the next year that they offered me the next available opening.”

Around 1988, The Brothers were reunited in medical arts. “Bill and I just took off from there,” says Ernie. “It just turned into a perfect team.”

Memorable assignments over the past 30 years included visits to NIH by every President going back to Jimmy Carter, events involving such celebrities as the Dalai Lama, Prince Charles and Mary Tyler Moore, the ACT UP demonstration of May 1990 (Ernie had been told not to cover it, but did anyway) and at least three decades of Camp Fantastic coverage.

Of the Bransons’ longevity, Ernie thinks that successive generations of NIH leadership appreciated the fact that they “got in and got out—that’s what they loved about the brothers. They have a job to do and so do we. The brothers didn’t belabor things.

“I feel so blessed,” Ernie concludes. “Many of our clients said they wished they had our jobs. It was hard work, but boy, what a great place to be.”