Patient-Scientists

Couple Turns Hand of Fate into Hand of Hope

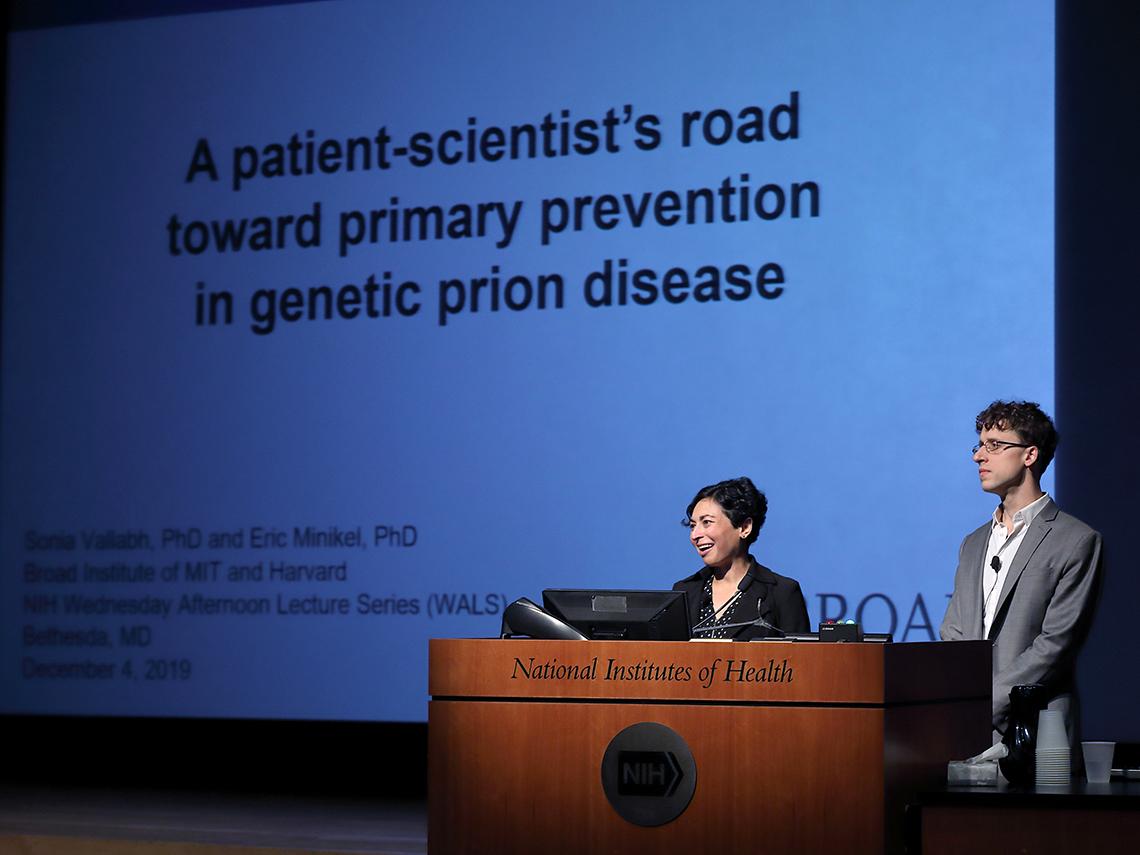

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

It turns out that not only can you tag-team a Wednesday Afternoon Lecture, but also you can tag-team a complete change of careers and an almost heroic attempt—via basic research—to thwart the timebomb ticking in a teammate’s genes—if you’ve got the right teammate.

There may not have been a more emotional presentation in series history than the one given recently by husband-and-wife team Dr. Sonia Vallabh and Dr. Eric Minikel, concerning Vallabh’s diagnosis as a carrier of a gene that puts her at high risk of suffering the disease that rapidly killed her mother in the prime of life.

Two years after they got married in August 2009, Vallabh, a Harvard-trained lawyer, and Minikel, an urban planner who had been a Chinese major as an undergrad, learned that Vallabh carried the gene for fatal familial insomnia, the prion disease that took her mother at age 52.

Their wedding had been the last time Vallabh had publicly enjoyed the mother—“who was a force behind the event”—she always knew. “It was the last family event for which she was healthy.” By February 2010, her mom’s vision began blurring and she was losing weight. By March, she was unable to finish a sentence. By June, she was on a feeding tube. She died in December.

Nonetheless, “she lasted twice as long as the median survival time” for people with her diagnosis, Minikel said.

“She had no diagnosis during her lifetime, only at autopsy,” said Vallabh.

“It was a horrible bombshell for us as we awaited” results of Vallabh’s genetic testing, she said. “It was a 50-50 risk for me. Most people choose to walk away and not get tested. I was advised to walk away from it.

“We realized immediately that we really needed to know,” she explained. “We couldn’t go back to the time when we didn’t know [I was at risk]. The only path available was forward.”

In 2011, Vallabh learned that the mutant variant she bore within her genes put her at more than 90 percent risk of prion disease.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“It usually occurs at midlife and is always fatal,” she said, describing the disease course. “You are healthy for decades and then there’s an amazingly steep downhill. Most patients die within a year of diagnosis.”

The couple had little scientific background, so they Googled “prion.” Thus began “a pretty engrossing quest that we would be shadowed by for the rest of our lives.”

They began taking night classes in science.

“I left my job within months of my diagnosis,” said Vallabh. “I became a lab tech at Massachusetts General Hospital, starting out on the bottom rung of a scientific career.

“Our initial goal was to become savvy consumers of scientific information,” she said. “We needed to know, ourselves, about any new developments or trials, and be proactive.”

In 2014, they enrolled at Harvard Medical School to pursue Ph.D.s, despite being advised against it.

“We found mentors at Broad [Institute of MIT and Harvard] right away,” said Vallabh.

They also had confidence in their strategy of learning not just about the science of prion disease, but also about the regulatory environment they would need to negotiate in order to run trials, validate biomarkers, recruit patients and advance therapies.

“We were interested in building a motivated cohort of people in my position—at-risk children of a deceased parent,” she explained.

Presently, Vallabh observes, “We realize that while we are very far from the end of this quest, we are also very far from the beginning.”

“The first thing we needed to know was ‘What is it and what are we going to do about it?’” said Minikel, taking over the narrative from his wife.

Prion disease is fairly rare, resulting in about one of every 5,000 deaths in the U.S., he reported. Fifteen percent of cases have a genetic cause and 85 percent arise sporadically.

“What are we up against with Sonia’s mutation?” they wanted to know. While all mutations are risk factors rather than the cause of prion disease, said Minikel, “Sonia is among those [whose mutation] almost always results in disease—about 90 percent of the time.”

Nonetheless, Vallabh used the word “lucky” repeatedly:

- All prion diseases work the same way, by misfolding proteins in a way that harms neurons; if you can lower the amount of abnormal protein, you have a chance at limiting or blocking the disease. There is both a good model of the disease—the mouse—and some promising therapies in ASOs—antisense oligonucleotides. “We are lucky to have a target we know is essential to the disease, and is also pretty much dispensable for normal life,” Vallabh said.

- The FDA has been receptive to their strategy, which mimics the path trodden by HIV therapy: reduce prion-related protein (PrP) with ASOs against PrP RNA, then measure PrP levels in cerebrospinal fluid. “[The FDA] has enthusiasm for the need for prevention, and enthusiasm for the need for a plan, but it has to be data-dependent,” Vallabh said.

- A large pharmaceutical company has given thumbs-up to their approach and is offering “a serious investment,” said Minikel. He also noted the benefit of laying groundwork in academia, where there were no concerns about data confidentiality.

- Their mentor at Harvard, Dr. Stuart Schreiber, allowed them to cut to the chase in their Ph.D. work (they both earned doctorates last year), focusing on prion disease. “We’d be 5 years behind where we are right now if we had hesitated [to get Ph.D.s],” Minikel said.

- Their first clinical research study was over-enrolled within 2 days with volunteers who are at risk of genetic prion disease. They also have more than 200 people enrolled in their registry.

- Studies in animals indicate that prevention may be possible in both the genetic and sporadic forms of prion disease, if therapy can begin early enough, before symptoms arise. “This is not a totally inactionable disease,” said Minikel.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Perhaps their greatest piece of luck was unearthed during the Q&A, when they were asked about the most difficult part of switching careers.

Minikel was funny: “So many different moments to choose from…” he began.

Vallabh arrived at the heart of what made their pivots possible: “It’s by having a teammate. I couldn’t do this alone.”

The auditorium erupted in applause.

The full talk is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=35113&bhcp=1.