Outgoing NCATS Director Austin Embraced Teamwork

Photo: NCATS

What’s the essential ingredient shared by an opera singer and a translational scientist?

For Dr. Christopher Austin, outgoing director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the answer is easy: teamwork.

“In music, you have to be listening to the other singers and instruments all the time, and you’re constantly adapting to what the larger group needs,” he explained.

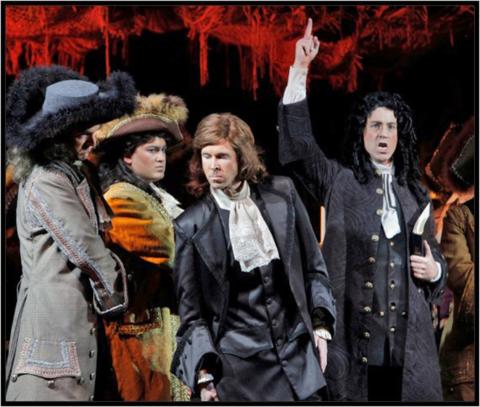

Austin has pursued his full-time scientific career while singing baritone roles part time in professional opera companies. That same team-based approach is crucial in translational science, where experts across disciplines and with different skill sets, work together to accelerate scientific discoveries into clinical interventions.

Millions of people are waiting for safe and effective treatments, and translational science can help deliver them sooner. The field focuses on optimizing the complex scientific and operational processes that underlie each step involved in translating an observation or discovery into a solution to improve health.

Austin leaves NCATS to become a partner at Flagship Pioneering, a Cambridge, Mass.-based life sciences organization, and chief executive officer of a new Flagship franchise company focused on developing therapies for genetically complex diseases.

Photo: Opera Vivente

As NCATS director, Austin spent nearly a decade championing translational science and establishing it as a field.

His career has spanned the spectrum of translational research in the public and private sectors. He left Merck Research Laboratories to join NIH in 2002 as senior advisor to the director for translational research at the National Human Genome Research Institute, where he was responsible for developing research programs leveraging results of the newly completed Human Genome Project.

While at NHGRI, Austin founded and directed the NIH Chemical Genomics Center, Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases program, Toxicology in the 21st Century initiative, and the NIH Center for Translational Therapeutics.

When NCATS launched in late 2011, Austin became the inaugural director of the Center’s Division of Preclinical Innovation, and then was appointed as NCATS director in 2012.

Austin often compared translational science to systematizing serendipity. Paraphrasing a former mentor, he said translational science can help guide research out of the trial-and-error “zone of chaos” and onto more predictable, successful and shorter pathways to new treatments.

Just as understanding the rules of physics or chemistry unlocked breakthroughs in those fields, understanding the science of translation could revolutionize how discoveries turn into interventions that improve our health.

NCATS has used its understanding of translation and commitment to teamwork-based solutions to develop innovative research approaches and technologies that work across scientific disciplines and diseases. These include tissue chips that speed drug research, automated drug repurposing, accelerated therapeutic discoveries for rare and neglected diseases, dozens of patents for preclinical innovations, and a nationwide network of clinical center partners to rapidly implement clinical trials in search of therapeutic solutions, including for Covid-19.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“Chris Austin is a great leader who commands, leads and inspires,” said Dr. Geoffrey Ling, professor of neurology, neurosurgery, anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

“NCATS has a unique mission of translating scientific advances into the clinic, and it’s one that Chris embraced and worked so hard to meet,” added Ling, who also has served as the director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Biological Technologies Office. “I am very grateful and proud to have worked with him on the NCATS advisory council.”

The NCATS culture encourages risk-taking by focusing on solving problems through teamwork, and Austin worked to build a diverse team whose success is built on orchestra-like collaboration and camaraderie.

“Chris Austin genuinely recognized that happy staff are productive staff—and he made it part of his job to ensure the former, so the latter comes naturally,” said Dr. Christine Colvis, director of NCATS Drug Development Partnership Programs.

Under Austin’s bold vision, NCATS’s primary goal has been to apply translational science approaches to improve the lives of people who need medical solutions.

“The most important element of any organization is for everyone in it to know why they’re doing something,” Austin said. “I wanted NCATS staff to have the patient with the disease as their reason for doing anything.”

Patient partnerships are integral to NCATS’s team-based approach.

“Chris Austin’s commitment to progress for patients is unwavering and has meant the world to the patient community,” noted Margaret Anderson, a managing director at Deloitte Consulting and a founding member of NCATS’s advisory council and Cures Acceleration Network Review Board.

Austin’s New England move inspired his mentor, NIH director Dr. Francis Collins, to pick up his guitar and play a take on Boston buskers’ immortal Charlie on the MTA. (See it here https://twitter.com/ncats_nih_gov/status/1382749470211850242)

While Austin will be moving, he won’t be trading his lifelong love of the Baltimore Orioles’ Memorial Stadium and Camden Yards for a newfound Fenway Park fandom.

As Austin readily concedes, there are some fields even translational science will never unite.